Ask Dr. D.

Questions from Readers

This month, I am debuting a new monthlyish feature, Ask Dr. D., in which readers, fans, and even grumps are invited to send in questions about, well, anything—recent posts, California, my writing, other people’s writing, music, psychoactive substances, cosmic background radiation, snack foods, whatever. I’ll answer as many as I can.

In 2021, a year I already prefer to 2020 in the way I already think Biden is a better president than Trump, I will put Ask Dr. D. behind the paywall, which means it will be available to paid subscribers only. But for now, the candy-man’s around, so enjoy.

Opportunity: until the end of the year, anyone who writes in with a question that I wind up using will get a free year’s subscription to the Burning Shore when I run the response. Please address your questions to asktheburningshore@gmail.com.

—Dr. D.

Erik I feel you are totally onto something in your post about paranoia and I don't know if you've read it but it feels connected to something Michael Taussig is getting at in his recent book Mastery of Non-Mastery in the Age of Meltdown—except his angle is that our time is one of "re-enchantment", a frightening enchantment . . . one so psychotic as to, perhaps, obviate paranoia? I mean, gone, gone, gone beyond, gone beyond paranoia into psychosis?

—Miranda, Olympia

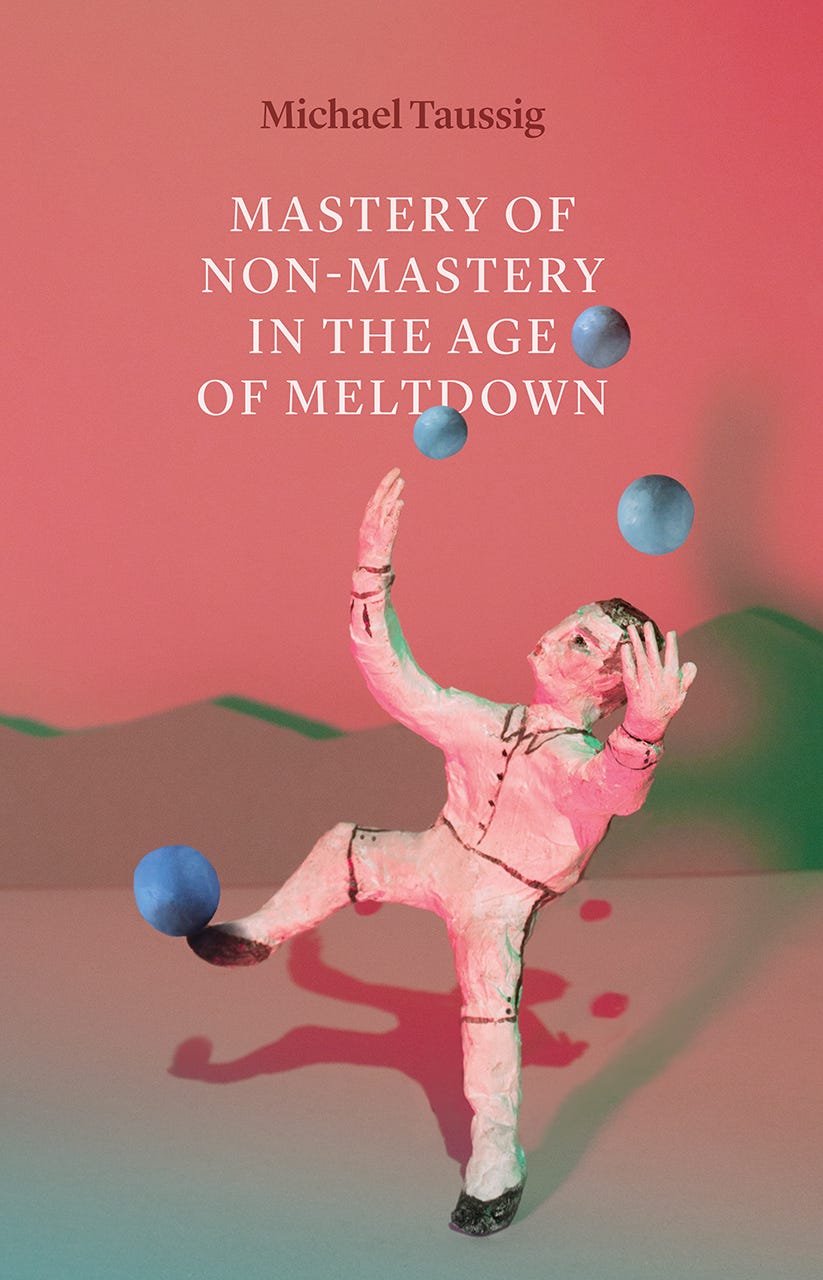

I am a huge fan of Taussig’s writings, which I read as a kind of magic square cornered with Benjamin and Bataille, mimesis and materialism. I wish his poetic anthropological theory was more widely read and appreciated by thoughtful folks interested in magic, psychedelia, indigenous cosmologies, and the re-enchantment of reality on a capitalist planet. His book on yagé in the Putumayo, Shamanism, Colonialism and the Wild Man: A Study in Terror and Healing (1987), is rarely discussed by today’s ayahuasca pundits, despite (or because of) its powerful combination of harsh historical spadework and dark surreal expression. But his work can be nourishing as well, like What Color is the Sacred? (2009), a book of sensuous mysteries.

The Mastery of Non-Mastery seems particularly special to me right now, even necessary. It resonates hard. Early in the book, Taussig describes showing an NYU seminar group two extraordinary ethnographic films, Jean Rouch’s Les maîtres fous (1955) and Gary Kildea and Jerry Leach’s Trobriand Cricket: An Ingenious Response to Colonialism (1974). I was there that day, some thirty years ago, and Taussig’s message about the vexed enchantments of mimesis—how a mutual and phantasmagoric mimicry complicates the power relations between colonized and colonialist—has always stayed with me.

I agree with you that Mastery of Non-Mastery’s take on the “re-enchantment of the world” is both sobering and urgent. Against the common claim that modernity represents a “dis-enchantment of the world” (Weber), I have always felt that enchantment never disappeared but went underground and in disguise. Still, the intentional revival of enchantment—as called for, say, by deep ecologists or Neopagans or Morris Berman in his great The Re-enchantment of the World (1981)—has been fitful and sometimes troubling. Taussig cuts through all that. For him, climate chaos is the vector of an in-your-face re-enchantment: hurricanes are mercurial, weather is weird, and the sun really is out to get you. Forget endless summer. We have entered an endless sunset where the categories of things, including ourselves, morph and bleed.

The light is strange now, that of dawn or twilight, when space and time dissolve. But it’s not dawn. It’s not twilight. It’s ten o’clock in the morning but the message seems clear—that with planetary destruction magic hour fitfully expands in stops and starts through the brain stem of being, or what’s left of the brain stem of being, now transmuted into a light show rippling with urgent, low-flying birds.

Written before Covid, or California’s apocalyptic fires, Taussig has still written the best thing I’ve read about the bizarre Orange Skies Day that descended on San Francisco last October, when high-elevation wildfire smoke went all Blade Runner 2049 in an atmosphere already invisibly charged with the miasma of the virus. For any who experienced it—the photos do not do it justice—high weirdness was upon us in its most baneful mode. In this book, Taussig nails both the magic and the fever of this mode, what he calls “magic hour gone wild.”

Though Taussig doesn’t talk about psychosis, I think I know what you mean: he is describing a sort of dark animist phantasmagoria that makes paranoia seem almost quaint, so “70s,” so all-too-humanly attached to systems of causal explanations and agents of control. It may be that we actually need to risk a sort of posthuman delirium to get beyond paranoia—the delirium of possession rites, or inter-species communication, or hypnogogia. When Taussig writes that “re-enchantment today entails fear and fascism,” that justifies or at least explains our paranoias. But “it also entails a newly aroused wonder about the natural world no less than its mimetic propensities.” This is a darkside wonder, a “poetics of the macabre,” and it arises from our stressed but knowing bodies, or what Taussig calls our “bodily unconscious.” Intuiting a world in its death throes, this wu wei, Brechtian, Deleuzian body-among-bodies still provides “the basis and hope of the mastery of non-mastery”—a practice of being and relating that makes a ground out of the threshold.

I come in peace. I love Jane’s Addiction’s Ritual de lo Habitual. I just bought the reissue, and decided to spend some time not working but reading about the album and I saw your 1990 Rolling Stone review. [In the review, I gave the record a cruel two out of five stars, declaring with the sneering swagger of youth that it sounded like “a fourteen-hour layover in Kashmir, a long-distance runaround with only Juggs magazine and a pack of purple Bubblicious to pass the time.” Ow!] The album is double-platinum. The same publication which published your review put it in the 2003 version of the silly top 500 albums of all time. So, I'm wondering if your view has changed wrt Ritual? Or if it's still just crap music that resonated with people? Wouldn't be the first time.....

—Andrew, NYC

From the late 80s to the mid 90s I was a smart-aleck rock writer, scribbling for Spin, Rolling Stone, the Village Voice, the LA Weekly, and other pubs. But I wasn’t a very good critic in some ways—I wrote extravagantly about bands that interested me conceptually or resonated with my weird, but I didn’t really argue from some commitment to well-formulated aesthetic or cultural values. This got me ahead of the curve on occasion (Pavement, Boards of Canada, the Magnetic Fields, Portishead) but also pretty far up my own cul-de-sac sometimes. The negative slams often seem particularly sloppy to me now, full of pee pee and cheap vinegar but not really making a point.

Jane’s Addiction seems interesting to me now, maybe even more so because of their novel articulation of a deeply Angeleno sensibility that bridged Sunset Strip and Melrose Ave., psychedelic renewal and “alternative”-pop crossover. Dave Navarro embodies the crucial link between metal and Mexican-Americans; Ritual begins with a Latina announcing the band in vibrant Spanish. And Perry Farrell’s trippy, sartorial hedonism now seems like an augury of Burner fabulosity and the whole “tranformative festival” lifestyle he helped invent and commercialize.

So I streamed Ritual through Spotify good and loud. But I can’t say my musical opinion changed much. A few great tunes, which I call out in my review, but a lot of bloat and wander and false import. I get the energy, but Nothing’s Shocking still seems a far more satisfying piece of work, chunkier, tighter, more hungry and more amused. But I did go a bit nutso with the RS review—today I would give Ritual three stars, and maybe nix the Juggs reference.

I am curious what your critical mind sees on the horizon with the burgeoning psychedelic "public health-mental health" industry, in particular the possible dystopic uses to which it will be put. I am in Oregon and we have Measure 109 being voted on. Seems progressive and needed doesn't it? Has your research led to things like; “Compulsory Moral Bioenhancement”? Or one better, “Covert Moral Bioenhancement”? What on earth would Huxley think?

—Zosimos, Oregon

This was the first I heard about “Compulsory Moral Bioenhancement” and the creepier “Covert Moral Bioenhancement,” but I have thought enough about biopolitics, behavior modification, and the biases of bioethics to not be surprised by either one. As far as I understand it, both of these concepts rest on the assumption that biotechnology will one day establish a reliable method for manipulating some sort of moral behavioral feature—like bio-hacking a predilection for violence or racism or sexual attraction towards children. The idea is that if such biotechnology were available—a big if, we should recall—then, ethically speaking, shouldn’t it be compulsory? And if it should be compulsory, why not just go ahead and make it covert, especially if that will increase its efficacy?

The road to hell, it seems, is paved not just with good intentions, but with building blocks of what William James called “medical materialism”—the reductionist idea that your individual will, tastes, and inclinations are entirely determined by hackable genes and programmable neuro-algorithms. What could possibly go wrong?

At the moment these arguments are still largely academic, which means that there’s a lot of posturing and jockeying going on. (I get the sense from the abstract that Mr. “Covert Moral Bioenhancement” is less Dr. Evil than a dude with a doctorate angling for tenure.) By “academic,” I also mean that these arguments are carried out within the discursive rule-sets laid down by specific disciplines, in this case bioethics, a discipline that purports to bring philosophical sophistry—excuse me, sophistication—to bear on matters of medical and public policy.

As far as I can see, bioethics is vitally important but super-normie, with none of the nuance or critical twist of someone like Taussig (see above). I suspect that the definition and formulation of what “morality” means in these discourses would surprise a lot of us, since they depend on notions of social engineering, genetic determinism, and utilitarian justifications for biotechnology that many of us wouldn’t consider very “moral” to begin with. That said, people who talk this way sit on boards that green-light far more powerful bio-political actors, so this isn’t just ivory tower hair-splitting. Good for you for tracking this stuff, but take it with a grain of social science salt.

At the same time, I think we need to take a broader view of “social engineering”, one that recognizes that we already live within deeply tweaked societies where concrete practices of diet, media, surveillance, and pharmacology are already radically reshaping (post)human subjectivity. We are already swimming in a sea of brainwash, in other words, but the currents that feed that sea are still various and contradictory enough, we hope, that One Ring does not rule them all. But here comes the thin edge of the wedge.

A few years ago, I met a younger fellow from Apple at a totally San Franciscoid gathering of earnest and well-meaning techies interested in ecology and spirituality. In a manner at once frank and sheepish, he acknowledged the ethical predicament his department and company was in: between smart phones and social media, technology already engineers thought and behavior. So don’t they have a responsibility to “nudge” things in the right direction? But what is the right direction? How do you nudge “transparently”? I remember his unspoken implication: should people like me be deciding this?

But there is another problem here, one shared by the bio-ethicists, as well as the recent Netflix doc The Social Dilemma. Whether their arguments are critical or proactive, all of these actors subscribe to a linear understanding of control and social/individual agency that may not reflect the real complexity involved.

Here psychedelics have something to say, because they have the capacity to raise the problem of control and programming to an agonizing fever pitch. Within the same trip, you can go from broken decision-making loops to the harrowing thought “Am I just a robot?”, then on to the recognition that ancestral trauma lies behind your core behavioral issues, before crowning the whole journey with the ecstatic fusion with some collective Being that, in those moments, seems to guide your very hand.

Welcome to the psycho-cybernetic-cosmic conundrum of control, one that all manner of Invisible Hands want to paper over as they grab for the tiller of the future. Will “They” use mainstream psychedelics to install an abstract concept of a Better World? Of course they will! What do you think Rick Doblin is up to with his mainstream do-goodery? In the face of such moral engineering, our job may be to continue to affirm the conundrum itself, to keep psychedelics weird, to keep insisting on the complexities, contingencies, and unknown agencies—including galactic or animist forces—that complicate the reductive anthropology that guides so many of these decision makers and power players. Maybe we can lift some pages from Taussig, and outflank the experts through the mastery of non-mastery…

Huxley is an interesting name to drop here because he writes about psychoactive social engineering in both dystopian and utopian keys. The soma of Brave New World—whose drugs don’t program moral behavior but distract and augment pleasure—is balanced by the widespread use of “moksha-medicine” to help cultivate the benign and idealistic Palanese society portrayed in Island. Pala sounds like a groovy place to wait out the crisis of global capitalism, but do its rulers also consider the moksha-medicine as a compulsory moral bio-enchancement?

Such language would not have shocked Huxley. When it came to the future of humanity, Huxley was a misanthropic pessimist, and hoped that psychedelics—and perhaps other means, even “any means necessary”—would serve as a reliable technology for manifesting higher human potential. He was also deeply familiar with evolutionary materialism and even eugenicist arguments for bio-social intervention through his brother Julian (for a fascinating intellectual biography of the two brothers, see R.S. Deese’s book We Are Amphibians). One thing is sure: reading about “Covert Moral Bioenhancement,” Huxley would not have batted an eye, blind or otherwise. He saw the Orange horizon now blazing before us all too clearly.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of The Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. The Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

I agree with Mr. James about your coolness! For whatever reason I just began reading my 3rd book on Kindle, Huxleys "The Perennial Philosophy" I love all his other books I have read and I agree he saw the orange horizon coming. I also for whaever reason, just viewed "The Social Dilema" Somehow I have managed all these years to not have a social media presence, I feel a bit of a lonely dinosaur, but also lucky! Thanks Dr.D

Yr the cool older brother I never had, turning me on to cool music and books. That’s gotta be worth $5 a month eh? Cheaper than the magazines I used to rely on for getting turned on to new stuff. This week its Taussig. Thanks Dr. D!