This is the second “Ask Dr. D.” post, and the last before I put the feature behind the paywall. A slew of excellent questions arrived at asktheburningshore@gmail.com, from the nitty-gritty to the hairy. An example of the latter included the following from Christine: “What do you think about time?” Yowza! I am up for some of the big questions, keep ‘em coming, but I want to resist my urge to be too thorough. “Off the cuff” is the goal, if not quite the rule.

Again, anyone whose questions I used here will receive a year’s subscription to Burning Shore. The questions below have been edited.

— Dr. D.

I have been wondering what happened to Ev, who was one of the three people in the experiment at La Chorrera described in High Weirdness. I’m curious about what became of her. — Thomas

As the only other person to directly participate in the Experiment besides Terence and Dennis McKenna, “Ev” would likely provide a very interesting angle on the brothers’ legendary jungle escapade. She was called Kumi at the time, and to date has not spoken publicly about her experience. The good news here is that my pal and colleague Graham St. John — a scholar of Burning Man and global psy-trance culture, and the author of Mystery School in Hyperspace, a great cultural history of DMT — is currently writing an intellectual biography of Terence, and is confident about eventually speaking with her.

The “You're as Cold as Ice” segment of This American Life’s 2008 "Mistakes Were Made" show has really stuck with me. What are some other worthwhile documentaries/books/articles about the creepy/gothic side of California counterculture and technofuturism in the 60s and 70s? — Ryan

A wonderful question. Much can be gained — and, perversely, enjoyed — by tuning into the “creepy/gothic” side of Cali counterculture and technofuturism. It’s important to push back against utopian hype, whether New Age or silicon, and these investigations help remind us about the ironies and limitations associated with human transformation.

I watch a lot of documentaries on religions and cults — or, to be more accurate, “cults.” (What’s a religion but a cult that won?) In the creepy/gothic West Coast category, you might check out Holy Hell (2016), Deprogrammed (2015), Transformation: The Life and Legacy of Werner Erhard (2006), Children of God (1994; superyuck), and funky exploitation fare like Satanis: The Devil's Mass (1970). As with the vast majority of cult docs, most of these are either fawning or demonizing, which makes good fictions, like Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master (2012), sometimes more satisfying. For a brilliantly twisty-but-sympathetic psychodrama about Cali New Age healing, Todd Haynes’ Safe (1995) cannot be beat.

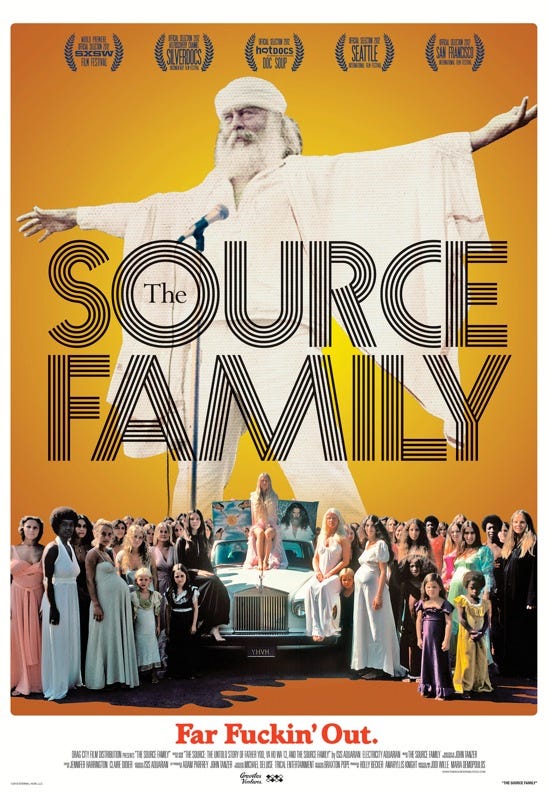

You also gotta see Maria Demopoulos and Jodi Wille’s fabulous 2012 doc on the Source Family, which I don’t think was a creepy scene — I explain why in the film — but some definitely do. For me, the story of Father Yod, and his many wives and rock albums, makes a good argument for why folks join cults and then stick around: however fucked up they may be, cults are also reality-bending social experiments that exuberantly subvert consensus norms. This makes them high-risk, grueling, exhilarating, and addictive — just like hard drugs, or extreme sports.

There are a number of solid Jim Jones/Jonestown docs out there, but I may like the 1980 docu-drama with Powers Boothe the most, partly because it still carries the trauma the nation experienced in late 1978. I will never forget my adolescent reaction to the bird’s-eye-view shot of the corpse-laden compound in Time magazine, nor my elementary school teacher Mr. Swenerton’s literally speechless incapacity to respond to our questions about what the fuck happened. Some researchers have found suspicious fingerprints throughout the story; for a clear overview of the conspiracies, check out this Rebecca Moore article from the Journal of Popular Culture, provided as part of SDSU’s awesome Jonestown collection.

Bookwise, I would strongly recommend the esoteric historian Gary Lachman’s Turn Off Your Mind (2001), a broad-minded if somewhat bitter dark-side countercultural history. James Riley presents a more apocalyptic vision of the same territory in his recent The Bad Trip (2019). If you can track down a copy, definitely read Mindfuckers: A Source Book on the Rise of Acid Fascism in America by David Felton (1972), which deals with Manson, the folk-music demagogue Mel Lyman on the East Coast, and the little-discussed Morehouse sex community in Contra Costa County.

Charles Manson is the ultimate creepy-crawler, of course, and we still can’t stop talking about him. I haven’t yet read Tom O’Neill’s CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties (2019) because it’s fucking long and clearly a bit messy. But you can listen to O’Neill’s popular interview with Joe Rogan, or read Adam Gorightly’s smoother Manson book, The Shadow over Santa Susana (2009) — which also covers the conspiratorial questions — or Ed Sanders’ classic The Family: The Story of Charles Manson’s Dune Buggy Attack Battalion (1971), whose first edition includes material on the deeply creepy/gothic Process Church that was later excised.

The unsettling side of technofuturism hasn’t been covered as much, but that means you get to do your own research! Rabbit holes a plenty await history-minded heads exploring the NorCal nexus that links Stanford Research Institute, Scientology, Willis Harman, Esalen, Ira Einhorn, “the Nine,” est, Doug Engelbart, Uri Geller, LSD, Andrija Puharich, Jacques Vallee, Anton LaVey, and the Menlo Park Veterans Hospital. Make sure to pack a lunch!

Or you could combine the technofuturism and cult stuff, in that chocolate-in-my-peanut-butter way, and dive into flying saucer cults. Jonathan Berman’s Calling All Earthlings (2015) is a poetic meta-documentary on George Van Tassell and the Integratron he built in Landers; Children of the Stars (2012) explores the Unarius group down in El Cajon, though you’re probably better off hunting down Unarius’ own cosmic ET videos.

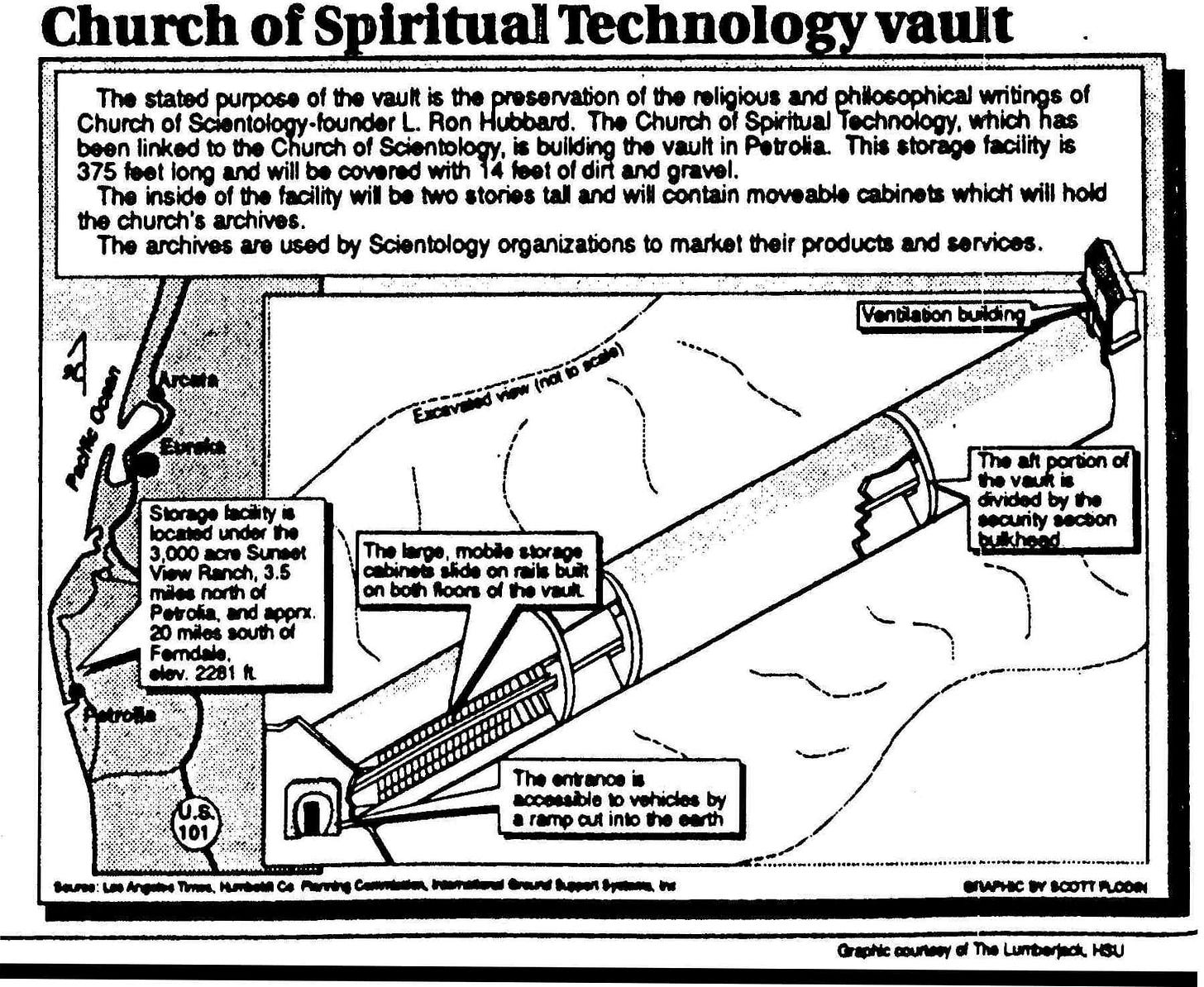

Another chocolate-and-peanut butter option is of course the Church of Scientology, with its suitcase E-meters, its space opera cosmology, its “spiritual technology.” I like withering L. Ron Hubbard bios like Bare-faced Messiah (1987) and A Piece of Blue Sky (1990), but it’s also interesting to approach from other angles. Far less demonizing is Hugh Urban’s slim The Church of Scientology (2011), in which the cool-headed religious scholar uses Scientology as a way to think about religion in the age of neoliberalism and copyright. A few nights ago, inspired by your question, I also watched Louis Theroux’s My Scientology Movie (2015) — coulda been edited down, but Theroux brings some refreshing deadpan humor to the thankless labor of trolling the Bridge to Total Freedom.

I’m a bit younger than you, but grew up in a similar-sounding West Coast environment, with counterculture and drugs aplenty. What stands out as I survey my past is how male it was. Most of my personal comrades in consciousness exploration, circa my late teens and twenties, were guys. Guys liked Wilson and Leary. Guys liked dropping acid. Guys liked drinking beer and talking about consciousness and philosophy and theory of knowledge all night. Guys liked Mondo 2000 magazine. Guys liked Discordianism. Guys liked this wacky new-ish thing called the Internet, which I adored and dove into, becoming a support worker at The Well.

I wasn’t too concerned about the guy-centricity of my interests, because hey, I like guys! Yes I also had women friends, and new grrly magazines like Bust to write for along with my contributions to Wired and Mondo — so why worry about gender? Largely, I didn’t. But it’s vexing to not see people like oneself represented in the search for consciousness, for higher, deeper, and weirder states of being.

Years later I went to a panel discussion at Burning Man that purported to be about the very future of humanity. I can’t remember who all the panelists were, but Daniel Pinchbeck was one. I remember that they were all men. I remember that the sea of festival-goers sitting on our butts on the dusty dome carpet skewed about 50/50 or maybe even 60/40 female to male. Yet during the Q&A, only men were selected to air their views or ask their questions.

I assume things have gotten a little more diverse since that day, but I still wonder: How could any of us have thought that our far-out scene of consciousness exploration was all that truthful, important, complete, or meaningful, when it was so limited? Why were we so complacent about the homogeneity, the smallness, of our band of merry travelers, given the vastness and variety of the territory through which we traipsed? Did the vast weirdness itself freak us out sufficiently that we sought refuge in the tried-and-true model of educated white men explaining the uni/multi-verse to the clueless masses, the unwitting Others? Or were we just un-woke products of our time, and who fuckin’ cares? — Tiffany, OR

You raise some important questions here, and I feel like you are also answering a lot of them yourself. To respond, I gotta step back, because my experience of these scenes and their discourses was a bit different. I grew up with West Coast weirdness, but I came of age intellectually on the East Coast. Though Yale was and is the very seat of privilege, the university was highly politicized in the ‘80s, and both feminism and LGBQ — not much T — discourse and activism were strong on campus and in (some) classes. When I moved to New York, I principally wrote for the Village Voice, which was zesty with political writing, both journalistic and cultural, much of it operating in a mode you might call Identity Politics 1.0. In those days, rock writing was as male-oriented as psychedelia, but many of my peers and editors doing cultural criticism at the paper were women, including Lisa Kennedy, Evelyn McDonnell, Ann Powers, Katherine Silberger, Beth Coleman, and Donna Gaines.

When I returned West and began participating in more psychedelic, Burner, and media-tech scenes, I still felt more like a journalistic and intellectual outsider than a full participant. My personal acid-futurism framework was a fractious assemblage already altered by Phil Dickean paranoia, anti-hippie media theory, and the critique of power. I never really drank the Kool-Aid, so I never felt either seduced or betrayed. I also met a lot of really interesting and influential women in these Bay-oriented scenes, including Brenda Laurel, St. Jude/Jude Milhon, Fire Erowid, Annie Oak, Maria Mangini, Ann Shulgin, Stara, and a certain scrappy writer who went by MagTif.

None of this answers your questions, however. The psychedelic, technofuturist scenes you describe have been (and continue to be in certain zones) overwhelmingly smug in their male dominance. Whatever else it is, I want to describe this thoughtless sexism as “lame,” but that particular pejorative term has been snatched away for us, for understandable reasons, though without any adequate replacement provided.

I’d like to think that things were worse with the Beats and hippies before. Just look at the photo from La Chorrera above: three guys geeking out, and two unengaged, possibly bored women. But the kind of panel you describe at Burning Man has been all too common throughout the broad, post-boomer generational cohort of freakdom. The tolerance that the scene showed for Pinchbeck’s aggressive and damaging womanizing is, unfortunately, all you need to know about where the real power lay. In this respect, as in too many others, I fear Gen X leans more boomer than not.

It feels like maybe your core question is whether this sexism and homogeneity invalidates the scene, its ideals, and your own fun and enthusiasm. I think the answer there depends, at least in part, on your current investments. In other words, how woke do you feel called to be? One way that people signify their wokeness, it appears to me, is to refuse to have any patience for the mixed bags of earlier social, political, and cultural situations. Instead, the past is condemned according to the strict and sometimes absolutist measures of the Now. As a gesture of the refusal to compromise, I get it; as a way of thinking about the actual past, it often seems naive and ahistorical. But hey — this is a Gen X dinosaur talking. By today’s woke standards, the Bay Areaish scenes you describe, though much more liberated than today’s techbro norms, are pretty much fails.

Your queasiness suggests something different to me than woke condemnation: a more vulnerable, even self-implicating reckoning with the hypocrisy, ignorance, self-satisfaction, and — forgive me — lameness of countercultural sexism. This can be a pretty disenchanting process. At the same time, the process opens up the possibility of redescribing the past in new ways, shedding light on valuable people and stories and currents that were obscured by all the blow-hard dudes. Sure Larry Harvey wore the hat as Burning Man’s talking head, but in many ways the ladies — including women few people know about, like my deceased friend Dana “Biz Babe” Harrison, who helped put the event on a solid financial footing — ran the show. Let’s remember that, and remember why we are remembering it.

I suspect that many people will continue to cancel the complexities of actual historical situations in the name of militant purity, and maybe that’s what identity politics looks like now. (I guess I preferred IP 1.0.) But I think it’s better to take the risk of doing what you are doing in your email: picking through the dust of the past, holding up the detritus to the light, and keeping your eyes peeled for precious metals amidst all the fool’s gold.

I have been surprised (as far as I have seen) not to have heard mention of Peter Lamborn Wilson in any of your podcasts or writings. Their religious studies bent, their sufism and hermeticism, their druggy weirdness, seem right up your alley, not to mention the connection between the TAZ and Burning Man. So what gives? — Graeme, Covelo

I agree that omission would be surprising if it were true. I first met Peter at the New York Open Center circa 1990, where we were both giving a lot of talks. I learned a good deal from his understanding of esotericism, his performance of independent scholarship, and his discourse of “poetic facts.” Wilson’s idea of “ontological anarchism” makes a brief appearance in High Weirdness, and I wrote a long profile of the man in the Village Voice in the mid-90s, a piece that can be found in my 2010 essay collection Nomad Codes.

What do you think about time? Is all time simultaneous in an eternal now that encompasses “past” and “future,” or is our standard perception of linear time the true reality? — Christine, the Midwest

Christine, I don’t have a fucking clue. I have an enormous respect for historical forces and the many transformations of matter in time, so I find it hard to shake a basically standard temporal framework in which we are surfing a forward-flowing froth of matter-energy-consciousness into an undetermined future. But then I talk to someone like Eric Wargo, and he reminds me that there are good reasons, of both science and spirit, to suspect we are following a locked groove inside a block universe where everything has basically already happened (a vision that neatly explains a number of psychedelic and paranormal anomalies). On top of all that, I’ve been blessed to occasionally dissolve into a still pool of timeless awareness, a shimmering nowspace that seemingly never ends until it does. What’s a poor mortal to do?

In general, I tend to adopt a pragmatic, low-bullshit attitude toward things, even as I acknowledge the magical multiplicity of reality by remaining sensitive to anomalies, contradictions, and hardcore paradox. It’s the kind of ontology that keeps you on your toes. So rather than worry that much about the “ultimate” nature of time, I accept in large part the conventional framework of linear cause-and-effect change. In turn I leave the question of whether the future is a dice roll or fixed in amber itself up to chance, or mood, or my proximity to the latest synchronicity. At the same time, I affirm that this view of temporal progression, like all conventions, is ghosted by the unconventional — by slips, stutters, and eternal voids whose enigmas must be tasted and considered thoroughly, like strange fish pulled from the stream, before you throw them back again, and flow on.

I hear that your Uncle B is the brains of the outfit. He also has the good looks. Is that true?? —Robert, Phoenix

I am contractually obligated to not answer this question, though I will note that my Uncle Bob’s physiognomy has been known to stop horses in their tracks.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of The Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. The Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Reluctant to ask this but do you or anyone you respect, not like The Rose of Paracelsus. I have only listened to the readings via The psychedelic salon and to be honest it is leaving me flat and I am surprised by the warmth of its reception. Partly the pace and reading is bothering me but I can usually get past that and am reluctant to purchase something that I am so disenchanted with. The essence of my non-enthusiasm is the scattershot absence of plot connecting characters and I really don't give a fuck about how clever and pretty these aimless harvard undergrads are which is all he seems to be saying . In fiction, action engages and description without momentum easily grows tedious. Maybe it begins to move and cohere and engage but how long does this take?

Dear Dr. D,

I listened to a Podcast recently who's guest, Michael Scott Alexander, wrote a book called "Making Peace with the Universe: Personal Crisis and Spiritual Healing". To sum up his thesis, respectfully, it could be called "the illuminated midlife crisis". He connects the post-30-year-old personal terror, followed by major spiritual and psychic awakenings of significant religious, philosophical, and artistic figures (William James, Buddha, Hamid Al-Ghazali, Mary Lou Williams....).

The connection he lands on apparently is one between the major spiritual traditions and the contemporary therapeutic process. Haven't read his book, but listening to his interview I thought about High Weirdness, which I did read, and how you make a personal crisis connection betwixt your three subjects. I plan on re-reading High Weirdness to see if maybe you actually mentioned the midlife-crisis-iness of it all, but it struck me that it's a thread that perhaps opens Exegesis, Cosmic Trigger and Archaic Revival to an even wider comparison. Does a clever mind that hit 40 and also traveled through chapel perilous end up writing Cosmic Trigger, while a materialism-addled simpleton finds a gray hair and buys a sports car, but both are expressions of something similarly archetypal?

There's so much contextual uniqueness to the Wilson/Dick/McKenna experiences that maybe the fear of mortality creep is cast in shadow. Or maybe I zoned out the part where you frame that in High Weirdness already.

Also, I noticed how much I've related to your weaving a narrative of transition struggle and reconciling the past in to, first, the final episodes of Expanding Mind, and now the Burning Shore. I'm in midlife, so I appreciate hearing that sentiment from your voice amongst the far out subjects I've been grokking from you since before my gut started expanding.

Thanks, and is there something to the above?

Sincerely,

Lower Back Pain in Los Angeles