Barrington Chapel

Those Who Know Do Not Tell

In many ways, you can chalk up my book High Weirdness to a case of arrested development. Here’s why: a lot of the obsessions that drove that project first hit home during my salad days, which were also, as you might guess, my weed days. During my years at Torrey Pines High in Del Mar, California—skater Tony Hawk’s alma mater; imagine Ridgemont High surrounded by chaparral—I encountered H. P. Lovecraft and Carlos Castaneda, Hunter S. Thompson and Aleister Crowley, the I Ching and The Psychedelic Experience, Blake and Freddy Nietzsche. I went to college when I was 17, and there it was Thomas Pynchon and Deleuze, RAW and PKD, Jean Baudrillard and Willis Barnstone’s The Other Bible, which was the first collection of ancient Near Eastern apocrypha I owned.

Many of these influences also provided something more like initiation. Usually we use that term to refer to a ritual process that marks one’s transition into a formal institution, like a religious sect or a fraternal order, or even, in more traditional societies, the state of adulthood. But in my lexicon, initiation also names a convulsive passage into a new way of seeing and being that, for better or worse, you cannot retreat from because it becomes part of who you are. And like the most transformative trips, such textual initiations often depend on an almost synchronistic alignment of set and setting, where the time and place of the encounter is as crucial as the material itself.

I can still recall the exact moment when, in the fall of 1985, a grad student at a Yale art school party reached into his shiny leather jacket and handed me, like a drug or some other contraband, the Semiotext(e) edition of Baudrillard’s Simulations. As many eighties intellectuals will recall, this Wonka bar-sized tract served as a golden ticket to the Virtual Reality Factory of postmodern media critique.

But that’s another story. Here I want to talk about a more delirious initiation that went down earlier that same year, an encounter that introduced me to the precise fusion of esotericism, altered states, and conspiracy theory that I explored in High Weirdness and have been continuing to track of late. Consider it my first glimpse of that paradoxical paranoiac condition that Robert Anton Wilson called Chapel Perilous.

I gobbled plenty of acid in high school, where I socialized with various stoners, geeks, and goths. I took AP classes and got good grades, which were a source of pothead pride as well as a get-out-of-jail free card as far as parental controls were concerned. I had always assumed I would go to Berkeley, an excellent freak-friendly university that my dad and aunt had attended and that laid out the red carpet for Ivy meat like me. But then a what-the-fuck application to some of those Ivies led to an even more extreme what-the-fuck matriculation at Yale, a prestigious school I basically knew nothing about.

Culturally speaking, my freshman year was a shocker. I only met a few psychedelicists, and the Deadheads on campus were prep-school kids whose insular ways creeped me out. I spent most of my time with music nerds and a crew of hilarious and whip-smart New Yorkers and Southerners, mostly public school kids who mostly just drank. I had fun, but I was also a discombobulated California transplant, and I often fantasized about transferring to Berkeley.

These days, I am very grateful for the years at Yale, part of a valuable decade I spent honing my mind on the East Coast. Though I was not initiated into any Yale societies, secret or otherwise, I was part of a smart-ass cabal of music writers and culture critics who later helped shape my early freelance career in New York, whose creative industries Yale basically functioned as a prep school for. But I don’t think I would have gone to Yale if the high school me had known the alienation and stress that lay in store.

In the spring of ’85, after my freshman year, I came back to Southern California for a few weeks to visit before heading north. The plan was to spend the summer in Berkeley with my high school girlfriend Elena, who had transferred to Cal from UCLA. After nine months of blue bloods and brainiacs and shitty beer, I was psyched to spend some time in California’s legacy university town. And as Cosmic Coincidence Control would have it, Elena had already secured a room in Barrington Hall, the most legendary and, by then, notorious of Berkeley's student-run co-ops.

Barrington had been a hotbed of political activism during the sixties and seventies, but while radical leftists and anarchists continued to stir the pot into the eighties, the four-story apartment block had become, by then, a large and tattered tent that cloaked all manner of countercultural intensities: punk rock nihilism, psychedelic mindfuckery, twisted pagan ways, and the devoted vending and consumption of drugs, with speed and heroin playing leading roles alongside the perrenial favorite of LSD.

Barrington was an animal house of high weirdness. In 1983, one student resident, who clearly did not know what she was getting herself into, submitted an official complaint about the following debits to her quality of life: “Live boa constrictor, fire, dried blood on her door, food and burning matches thrown at dinner, person wandering through halls brandishing a whip and striking the walls with it.” Said halls were also covered with prankster graffiti and hippie murals, and reeked of cat piss. Slogans spray-painted outside the building captured the unnerving tenor of the place. A large “LSD” had been painted onto the tarmac of Haste Street to the north in order to jog the memories of any high-flying trippers contemplating Icarus moves from the roof. Another wall, to the south entrance if I recall, carried the following phrase:

Those who say don’t know, those who know don’t say.

I was deep enough into Taoism at the time to recognize this line as a corruption of Lao-tse, the ancient sage who was seemingly offering up a cautionary reminder about the difference between language and being. But in the dank and sometimes criminal environs of Barrington, where it served as both motto and watchword, the phrase took on an ominous and conspiratorial edge.

I got a preview of this vibe before I even arrived in Berkeley. When I was still down in North County, I received a call from Elena, whose tone of voice immediately stood my hair on end. In measured but eerie tones, she explained that she and a friend at Barrington had dropped LSD a couple days earlier, but that they were both still high, long after the normal eight- to twelve-hour arc should have set them back down. Only they weren’t high, exactly. While the first hours of the experience had been typically trippy, they had then passed into profoundly unfamiliar terrain, free of eye candy and soaked in a peculiar clarity. Calmly and lucidly, without any of the eye-popping mania of your standard drug revelator, Elena explained that she could understand what poets were trying to say with their poems, what philosophers were trying to communicate with their words. This didn’t make much sense to me. But it was clear that whatever her new knowledge was, it did not feel like liberation, but something more like a trap.

We kept talking over the next day or so, as the weird trip faded away. But the uncanny hit my spidey-sense had taken during that phone call may have lent a certain caution to my arrival at Barrington shortly thereafter. I largely stayed away from the common areas and didn’t participate in any of the legendary acid-fueled “wine parties.” I hung out with Elena, worked temp in downtown San Francisco, and feasted on Berkeley’s book stores, cinemas, and coffee shops. We had a couple of freaky roommates come and go, and a number of amusing Deadheads and dealers drop by, some of whom I encountered years later in odd, synchronistic circumstances. But I mostly stuck to an MO that would come to define much of the subcultural reporting to come: hanging at the edge of the fire, inhaling the ambient atmospheres, and making connections with a few of the friendlier and more well-read habitués.

One of the fellows I got to know was a pasty-faced and reportedly wealthy kid from New York. Aaron was no longer a student, and lived in a utility closet on one of the upper floors. He slept in a chair with his head on a desk stacked high with Burroughs and Surrealist literature, an arrangement accessorized with a live tarantula under glass, and, dangling from an upper shelf like the fetish it was, a single blue spoon. Aaron invited me into his lair one memorable afternoon, closed the door and read me what seemed a ream or two of junky prose.

I became much better friends with Bill, a short, wiry, and intensely intelligent guy who had lived in and out of the underground for years. He approved of my Hüsker Dü t-shirt, and invited me to his neatly appointed room, where we swapped enthusiasms. There Bill did me the eternal favor of turning me on to Philip K. Dick, an obscure writer in those years, largely out of print but correspondingly cultish. (The tag “Am-Web,” a housing complex in Dick’s Martian Time-Slip, was stenciled on the alley side of Barrington.) By the end of the summer, Bill had a heroin habit, and went to the desert to kick.

I didn’t end up reading PKD until my sophomore year, but Barrington did provide the scene of my first really deep dive into esoterica. I first learned about Aleister Crowley in high school, by way of Jimmy Page of course, and had already consumed the scandalous Symonds biography before destroying it during my brief born-again phase (another story, also itching to be told). In Berkeley I bought my first Thoth deck, and closely studied Crowley’s book on the subject. But the real Great Work of the summer was Wilson and Shea’s Illuminatus! trilogy (in the Dell single-volume edition), along with supporting texts like the Principia Discordia, Cosmic Trigger, and Prometheus Rising, all of which were easy enough to pick up at Moe’s or Shambhala on Telegraph Ave.

I now consider this whole mind-blowing course of reading and discovery as an initiation into esoteric conspiracism. In broad terms, esotericism and conspiracy theory share many features: they draw correspondences between superficially unrelated objects and events, they are both forms of “rejected knowledge,” and they suggest that our ordinary minds and desires are shaped by invisible and covert forces. The notion of “hidden masters,” which is something shared by Theosophy and many secret societies, is also key for many conspiracists, even in their more secular formulations. Indeed, the first proper conspiracy theories arose in reaction to the French Revolution—the original bonfire of “traditional values,” and frequently blamed, even then, on the Illuminati, an eighteenth-century Masonic splinter group that lies at the heart of Illuminatus! and much of today’s conspiracy culture.

In the late nineteenth century, this reactionary conspiracy current got a feverish American twist when it converged with premillennialist fundamentalism, whose dystopian vision of the Antichrist’s reign at the end of days laid the apocalyptic template for all manner of control society terrors to come. In some corners, these prophetic fears also fused with Populist critiques of crony capitalism and the various corporate octopi that dominated American (and Californian) enterprise.

By the late sixties, when Wilson and Shea began writing their novel, this old-school current was represented by the John Birch Society, which broadcast fears of a Satanic New World Order they believed was being installed by the UN, international bankers, and secretive global organizations, including the Elders of Zion. At the same time, a more liberal set of conspiracy theories were thriving in the shadows cast by the Warren Commission’s—how to say it—rickety conclusion that Lee Harvey Oswald shot JFK all by his lonesome. This is, in fact, when “conspiracy theory” became a term of art, as mainstream authorities attempted to marginalize a variety of nitty-gritty JFK counter-narratives, often featuring massive amounts of detail about America’s nefarious and networked underbelly.

The dirty deeds of Dealey Plaza in turn helped seed a general culture of paranoia that swallowed up many participants in the New Left and the freak scene by the end of the sixties—sometimes for very good reasons (police and FBI infiltration was widespread) and sometimes for wobbly ones (lots of paranoia-inducing drugs, especially speed, weed, and LSD). By 1975, when Illuminatus! appeared, some of these dark hunches had also been definitively confirmed by the publication of the Pentagon Papers, the exposure of the Watergate cover-up, and the Church Committee’s uncovering of COINTELPRO and Project MKUltra.

The fact that actual conspiracies shaped the politics of the sixties underscores a point made by a few disappointed readers of my last post, “The Wilderness of Mirrors”: many conspiracies are real, and discussions of “conspiracy theory” that emphasize psychology, myth, and media dynamics serve to keep them hidden, and to subject researchers to a kind of gas-lighting. This is one of the many reasons that writing about conspiracism is hard: the thing itself is a messy amalgam of objective and subjective elements, and, like the thought processes of actual clinical paranoids, often fuses and confuses rationality and phantasm, logic and more labile ways of weaving the world. But given the pervasiveness of actual political and corporate conspiracies, it makes sense that investigators should rigorously separate rational accounts of conspiracies from fantasies, so as to assess the former with the analytic tools capable of revealing public truth. Even Robert Anton Wilson believed this to some degree, and, for example, spent a lot of time researching the hairy enigmas surrounding the 1978 murder of Italian prime minister Aldo Moro. But as I wrote in High Weirdness,

Illuminatus! is founded on the opposite premise: that the distinction between the political discourse of conspiracy and the fantastic fabulations of the paranoid, psychedelic, or occult mind is impossible to locate. As such, Wilson and Shea go out of their way to frame conspiracy theories—even those rooted in historical truth—as political forms of mystery religion. Meanwhile, they represent gnosis and other forms of mystical experience as inherently political, always enmeshed in the sort of control systems described by William Burroughs, in which esoteric truths are always potentially weaponized. Politics, for them, is inextricable from cosmic paranoia.

In building their labyrinth of funhouse mirrors, Wilson and Shea helped to craft what we might think of as a postmodern mode of conspiracism, one that brought classic Illuminati paranoia together with the shadow struggles of postwar control societies—an “alchemical wedding” that was then juiced up with the intoxications of a psychedelicized and sometimes playful occult revival. Just as significant, however, was Wilson and Shea’s decision to render their conspiracy narratives as a form of entertainment—freaky stoner kicks that reveled in the loss of grand narratives while manifesting a spirit of cognitive liberty that lies halfway between spiritual illumination and the lulz.

All this seems ominously prophetic today. In 1985, to me anyway, it mostly seemed like a freak lark, a madcap cruise along some born-to-be-wild highway. But it was no simple highway. Illuminatus! is a self-consciously initiatory text, a mindfuck in other words, and the whole point such transformations is that you can’t turn around and go back the way you came in. You’ve crossed a threshold, maybe unawares, but there you are. Though others have gone before you, the path itself—the exit from the Chapel even—is utterly your own. And if you fall, you fall alone.

In the middle of July that summer, Elena and I piled into my Datsun and drove down to Ventura County Fairgrounds, just south of Santa Barbara, to see the Grateful Dead. I had already been bone-danced into the cult by that point, and had seen the band half a dozen times, including the July 1984 weekend shows at Ventura, which in those years served as SoCal’s cowpoke rejoinder to the leafy Ren Faire glade of Frost up north.

The Fairgrounds lay right on the shore, which in those days meant that once you got through the gates into the parking lot, the freaks pretty much owned the space. Law enforcement seemed minimal, and a festival spirit took hold. Alongside the usual VW caravansaries, freak clans camped on the beach or in the animal stalls, which grew boisterous in the evenings, with film screenings and hoedowns and grilled cheese mongers and all manner of swaps and deals. In the afternoons, we packed into the open-air rodeo ring, with shaded bleachers off to one side, and danced under the sun. One afternoon, the band was unusually late to take the stage, until, from our perch in the stands, we glimpsed a long procession of Harleys grumble into the backstage area with an almost regal calm. A few minutes later, the boys kicked into the set.

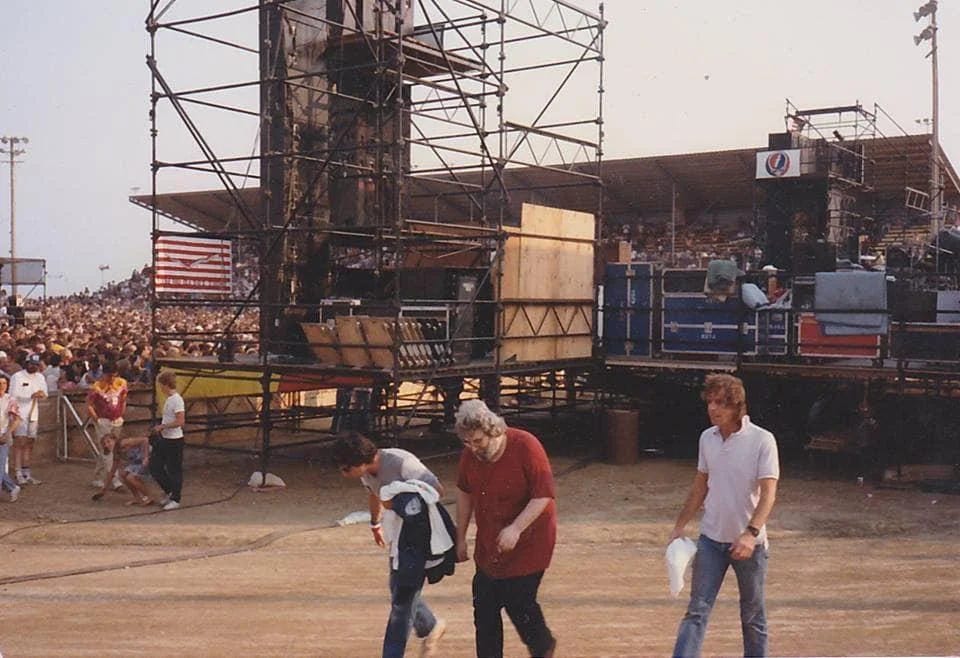

Ventura was where my initiation into the Dead’s honky-tonk tantra went down. Sure I dug the hippie jams—which could go pretty wonky in those days, admittedly—but that’s not what did it. What did it was the sound stage, which was plonked down in the middle of the ring (you can glimpse it to the far left in the shot above). This meant that if you were standing behind the sound stage, you couldn’t see the band.

Stumbling into this dusty cauldron that first summer after high school, I discovered a temporary autonomous zone of dance magic. Freed from the magnetic spectacle of the stage, power dancers could generate their own basins of attraction, spinning together like a Calder mobile in syncopated overdrive, while mystic winks kept the com lines open. Here was a scene that in some sense went all the way back to the Haight-Ashbury, when the bands that so many now revere were not as important as the wild, freaky, ecstatic boogie they occasioned, a collective and deeply psychedelic current of Dionysian dance that, after two decades of flow, now galvanized me as well, throwing my bones into the grooves like dice.

Loaded dice are preferable, of course, and so, after Elena and I arrived the following summer, we spent our first hours hunting for LSD. We preferred to score from folks we knew, but we didn’t run into any of my Del Mar cronies. Off on her own, Elena stumbled into someone she vaguely knew from Barrington Hall, and walked away with a few tabs of blotter.

The acid came on smooth, and the first set kicked into gear with a luscious, loping “Fire on the Mountain”, which present California circumstances require me to remind everyone was written by Mickey Hart and Robert Hunter as a fire consumed the hills above Hart’s Marin County ranch, and which, that July in 1985, was presumably inspired by the Wheeler Fire then raging in the mountains behind Ventura. During the chorus, it hit me: Fire on the Mountain is also a description of the two trigrams that make up the 56th hexagram in the I Ching, known in the Wilhelm/Baynes translation as “The Wanderer.” Long distance runner, what you standing there for? Get up, get off, get out of the door…

I stuck to the pocket behind the sound-stage for most of the set, tuned to the dancing bodies around me, as we swapped moves like smiles or guitar licks. But then something happened. I don’t remember what the tune was—it might have been the set closer “The Music Never Stopped”—but the music, well, stopped. Or at least grew terribly muffled and faint, as if my hearing were submerged under water. And not just my hearing: my limbs became wet noodles, I no longer felt the sea breeze stroke my skin, and the groove I had been riding grew muddy and turbid. The clarity of realtime sensation returned once or twice, like sunshine on a cloudy day, but whatever nerd demon had seized the knobs of my nervous system then unleashed a filter sweep that sapped vividness from my signals. The sludgy anti-groove effect this produced not only freaked me out, but sent ripples through the local mindmeld. My fellow dancers, my cosmic comrades, turned on me with puzzlement or irritation, or drifted rapidly away from the bummer I had become.

Time to flee. I found Elena, who also seemed out of it, and we headed up into a far corner of the bleachers. I remember gazing over the crowd, above the palm trees, out towards the smoky Topatopa mountains to the north. Now the subtler effects of the headfuck made themselves known. It was hard enough to grok at the time, let alone to recall thirty-five years later, but it wasn’t “psychedelic” in any sense that I have known before or since. There were no energetic rushes, no visual stutters, no metamorphic metaphors—indeed, very little dynamics at all. The mindscape was dry and empty and clear, a limpid limbo that stretched far into a nothing that was nonetheless known.

A couple weeks ago, as I was wondering about whether and how to tell this story, a poem showed up in my Twitter feed. I recognized in it the voice of Wallace Stevens, one of my favorite poets, but I didn’t know the piece itself, which is called “Crude Foyer.” “Thought is false happiness,” Stevens begins, before outlining the possibility

That there lies at the end of thought

A foyer of the spirit in a landscape

Of the mind, in which we sit

And wear humanity's bleak crown…

The headspace I was in felt a lot like this foyer, an “end of thought” zone that recalled Elena’s claim that she understood what poets and philosophers were only pointing at. Yes, she told me now, this was the same state that had taken her at Barrington earlier that summer. So there we were: a void in amber. We stayed in the bleachers for the rest of the show, because there was really nowhere else to go, nowhere at all.

Elena and I remained shattered and strange the rest of that weekend, as my Del Mar friends later confirmed. I don’t remember the Sunday show, or packing up to leave. At least the mindfunk itself wore off by the time we got back to Barrington, whose tagged and creaking frame now seemed more ominous and implacable than before.

One possibility was that some Barringtonian was dealing a peculiar, dissociative psychedelic that was not LSD. But I’ve talked to a number of psychedelic chemists and psychonauts over the years, and nothing I have heard of, nor any alphabetical I have sampled, sticks any recognizable meat to those bones. Another possibility is that we ate some “bad acid,” or at least weird acid, but even if we ignore for the moment the question of what makes good acid good, and weird acid weird, none of the other difficult lysergic limbos I have ever visited are even in the ballpark. That’s not proof of course, the LSD possibilities were squelched a month or so after Ventura when, following an understandable spell of sobriety, Elena and I scored some “Quaaludes” from a Barringtonian upstairs. Within the hour, our pleasure cruise had morphed into a modest analog of the same bleak trance.

WTF? Was this some collective anti-hallucination conjured by Elena, her friend, and me? Was it the parasitic mindstream of a Barrington egregore whipped up by feral void wizards in the basement? Or were we the victims of a drug cult recruitment campaign that slipped MK head-sauce into different drugs in order to ensorcell co-op newbies with varying tastes in psychoactives? I wanted to ask my Barrington friends about it, to track down the dealer from Ventura, but there was a peculiar force-field around the whole topic, which, you must admit, sounds kinda nebulous. Those who say don’t know, those who know don’t say…

Here we come to the anticlimax of the story. Despite having a head primed for esoteric coincidences and paranoid plots, despite the unwholesome witchery of Barrington, and despite my direct encounter with the Cosmic Zero, I did not lose my shit. It was as if I had reached the threshold of Chapel Perilous, but then stepped back into the still open air. Things were starting to drift with Elena, but for the remainder of the summer, I just plugged along, working my temp job in SF, catching every Janus film I could at University Cinema, and haunting Moe’s and Rasuptin Records. When I left Barrington to return East, I managed to escape without a drug addiction or, even more dangerously, the Answer to the Riddle.

I am not sure what exactly kept my head on my shoulders, but I am pretty sure that RAW had something to do with it. Illuminatus! may be a pathogenic meme machine, but Cosmic Trigger, in which Wilson finds himself in Chapel Perilous following years of hardcore brain-state experiments, offers a kind of homeopathic cure. As I discuss in High Weirdness, Wilson’s escape from the Chapel did not depend on a rationalist return to common sense, but on a more tricksy stance of radical pluralism and perspective selection that Wilson calls “multiple model agnosticism.” In HW, I linked this with what I call the tight-rope walk: the art of staying upright as you cross over the void by maintaining a balance of pragmatic skepticism and visionary curiosity, of reason and enchantment, of empirical knowing and Zen non-knowing.

Or maybe it’s just my temperament. I have always mixed caution with dash, and have often wrestled with an ambivalence that, depending on how you slice it, either holds me back or holds me aloof, balancing on the n-dash that forges the participant-observer. It’s not that I am incapable of paranormal blasts, or holy moments, or deeply paranoid jags—some of which I will continue to explore here. At times I have been utterly convinced of the absolute reality of vast and nefarious conspiracies that exist on cosmological, technological, and political levels. But like every thing of thought, these mega narratives (mostly) fragment and pass, an impermanence whose recognition also seems key to the whole waking-up thing. Perhaps visionary convictions, like all thoughts, follow their own rhythm, a kind of oscillation or pulse between affirmation, self-observation, and skeptical deconstruction.

But I did carry something back with me from Barrington Chapel, something that would become woven into my sensibility and my studies like the gnostic homeoplasmate I read about in PKD’s VALIS only a few months down the road. I still don’t know what that something is, but sometimes I catch a glimpse of it, flickering between the dawn and the dark of night.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of The Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. As a bonus you will get a paid-subscriber-only audio recording of all new posts. The Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so maybe pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

All praise the Bong Monitor regardless.

Oh and thanks for the comments on the radioman persona. I like your reading, of course it flatters. While I have gotten lots of feedback on specific books and pieces I have written, I have very little sense of the overall persona vibe. But a question: why a war? Or rather, what is the war?