California Flickers

Reviews, News, and Notes

A few weeks ago, I was visited by a wonderful poet friend who, like many minimally encashed artists and writers, was ejected from the Bay Area a couple years ago and now resides in a less economically brutal elsewhere. Good for her. I wanted to show her a good time though, some slice of San Francisco she may never have known. Then I saw that her visit coincided with the inaugural fall program of San Francisco’s Other Cinema, a series devoted to experimental, political, archival, weird, and fucked-up film that has been blowing Frisco minds for, like, forty years. The series unspools most Saturday nights at the Artists’ Television Access, a center for critical images and underground culture that sticks out like a sore punk-rock thumb along the gentrified hipbro row of Valencia Street. Our good time was locked and loaded.

Other Cinema is run by my old pal Craig Baldwin, a frazzled filmmaker, archivist, theorist, and collector who somehow keeps ATA running in the face of it all. Craig has made a bunch of excellent and provocative films, often relying on assemblage techniques that draw from his vast archive of industrial shorts, B-movies, amateur Super 8s, advertisements, and uncategorizable anomalies. Baldwin’s films include meditations on Negativland-style appropriation (Sonic Outlaws), paranormal media theory (Spectres of the Spectrum), a partly live-action narrative riffing on Scientology and Jack Parsons lore (Mock Up on Mu), and an extraordinary phantasmic political critique of American adventurism (Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America, which you should watch immediately). Craig interviewed me for one of these films, and also invited me to do a number of “performance lectures” at ATA back in the day. It’s an analog place, and we painstakingly cued up dozens of VHS tapes for each lecture, which wove together film clips and my feverish rants about topics like bardo worlds, psychedelic trips, and Lovecraftian mind parasites. These remain some of the best presentations I have ever given, but were never recorded, both by sloth and by design.

The program the poet and I caught that night was named for a classically Baldwin theme: “Archive Fever.” It featured a pre-show auction of select pieces from his large collection of T-shirts, also immortalized in a new book called 222. The shorts he then screened reminded me, once again, of the vast, poignant, and elliptical richness that lies irredeemably beyond the filmic universe available for download or streaming. We witnessed a 1953 tribute to LA sanitation workers, whose rescue of “Treasures in a Garbage Can” gave the evening its theme. There was an IBM paean to future tech, a California tsunami public service apocalypse, and a mid-70s Oscar Mayer industrial film whose greasy weiner Taylorism changed me for all time. Religious weirdness, as usual, was never far from the 16 mm scene: we saw a racist Mormon travelogue, an early 70s Christian cult exposure (featuring ex-Panther Eldridge Cleaver), and, most incredibly, an amateur 1956 Kodachrome tourist recording of a Trinidadian carnival saturated with devils and costumed deliria.

The evening reminded me of the intense and critical pleasures of marginalia, the treasures of the garbage can, and the jewels we sometimes grasp from the raging stream of oblivion. One thing I did not anticipate about growing older is that the world that one has known — in this case the world of the analog underground — disappears at about the same rate that the actual people you have known and loved disappear, whether they drift away, go nuts, give up, or die. Craig himself has been wrestling hard with the Big C for some time, and I was amazed that he had the energy to mount another season of Other Cinema. Actually I suspect he doesn’t have the energy, but he did it anyway, which is very Craig. If you are in the neighborhood, you should swing by and sniff the old school, avant-underground magic, because it’s going to flicker out eventually, and probably sooner than later.

Upcoming Event

• Jordan Belson: COSMOGENESIS: A Symposium of Transcendental Films, Lectures, Performances, and Visual Arts

As arts go, film stands out as a relatively massive enterprise requiring scores if not hundreds if not thousands of creatives, actors, techs, and support staff. Experimental film is often produced on a vastly smaller scale, but for some DIY filmmakers, working in documentary, abstraction, or animation, the numbers sometimes boil down to one single diligent visionary, whose obsessive labor makes this most “technological” of arts handmade, intimate, and, occasionally, the vehicle of a singular but utterly transcendental vision.

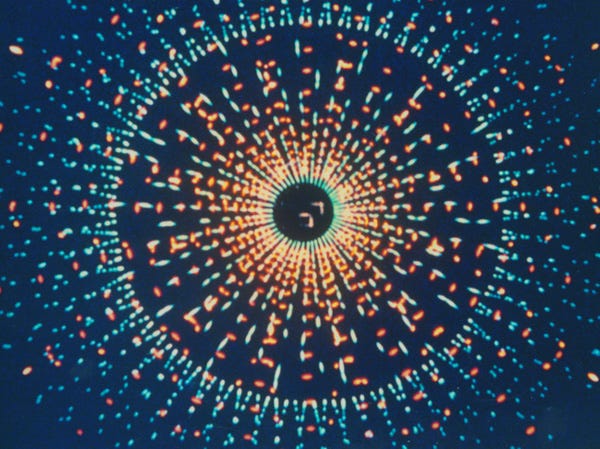

Jordan Belson (1926-2011) was one of those singular visionaries, a remarkable Bay Area-based artist and filmmaker whose meditative, trance-like 16mm shorts, most of which Belson created on a light table of his own design, are numinous, poetic, and aesthetically ravishing. Having already turned on before the Beats showed up — he was an old friend of Harry Smith when Smith still lived in the Bay — Belson walked his path of art mysticism for many decades, studying meditation, yoga, and comparative religion, and consuming the occasional visionary compound. His lifelong devotion to the Mystery shows in the best of ways. Films like “Samadhi”, “Cosmos”, and “Chakra” hand your third eye to you on a mandalic platter, plumbing the esoteric implications of abstraction so fundamental to modern art. But they also capture aspects of the internal phenomenology of meditation and trance like few other visual artifacts I know. Forget 2001: A Space Odyssey; in terms of cosmic cinema, this is The Shit.

Partly because of his own exacting demands for screening conditions, Belson’s films are rarely seen in all their analog glory. This coming weekend, San Francisco’s Gray Area will be showing quality prints of many of his films, including rarities, newly-struck 16 mm films, and digital preservations. That’s already awesome, but only part of the package. Over the weekend, Gray Area will also host a deeply thoughtful symposium devoted to unpacking some of the fascinating histories and implications of Belson’s work. Presenters will include myself (hosting some Friday night screenings), curator extraordinaire and all around mensch Raymond Foye, Bruce Conner restorationist Ross Lipman, and Belson expert L u m i a. I am particularly looking forward to a presentation and musical performance from Haight Street Moog pioneer (and Aoxomoxoa contributor) Doug McKechnie, one of the last folks living who attended the multimedia Vortex concerts that Belson staged with Henry Jacobs at the Morrison Planetarium in Golden Gate Park back in the golden day. Like Belson’s films themselves, COSMOGENESIS looks to be a rare blend of esoteric aesthetics, cosmic reflections, and finely-honed craft. Tickets and more info.

Documenting Californians

• O Mother Gaia: The World of Gary Snyder

Though physically a bit of a squirt, the poet Gary Snyder remains a towering figure of earth verse, bioregional activism, and backcountry Zen. After meeting the young poets Lew Welch and Philip Whalen at Reed College in the late 1940s, and then gallivanting through the Bay Area’s poetry circles in the 50s, Snyder came to articulate a rural, West Coast take that paralleled the Beats’ otherwise heavily urban sensibility. His friend Jack Kerouac immortalized a version of the Snyder vibe in the 1958 novel The Dharma Bums, whose central hero Japhy Ryder is based on Snyder and his mountain hermit calls for a “rucksack revolution.”

Along with his deeply informed study of Buddhism and Zen, Snyder’s wilderness predilections, embodied in his spare and vividly concrete poems, helped establish the organic and Eastern turn of the hippies who followed the Beats, as well as inspiring the works and lives of younger figures like Dale Pendell and Peter Coyote. Snyder himself mostly skipped the hippie thing. Though he appeared at the Human Be-In and participated in a the famous houseboat summit with Tim Leary, Allen Ginsberg, and Alan Watts in 1967, Snyder spent most of the 1960s at monasteries in Japan. In 1970, he moved to the San Juan Ridge in the Sierra Nevada foothills, building a home without power tools and catalyzing an informal intentional community and a stab at bioregionalism and “non-mindless anarchism.”

O Mother Gaia was shot by Colin Still, a British filmmaker who started interviewing Gary and some of his cronies back in 1995. The BBC ran a shorter version of the film, and when the material reverted to Still, he finished it as a feature, just in time for Snyder’s 95th birthday. Accordingly, the film smears time in an odd but not unpleasant way, as ghosts like Ginsberg and Snyder’s wife Carole Koda, who died in 2006, appear alongside living sources like Michael McClure, Jane Hirshfield, and Peter Coyote, all of whom add immeasurably to the film — in part by watering down Snyder’s air of patriarchal command. I have a lot of respect for Snyder, and though this film helped me appreciate his verse more than before, I still prefer his essays to most of his poetry. But I also found him a bit insufferable at times, so rugged, so competent, and so keenly self-assured. (One wag I vaguely remember called him the Marlboro Man of American poetry.) You know the guy’s knives are freshly sharpened, the tomatoes flourishing in the garden, the notebooks — as he shows off here — fantastically in order.

While the film suffers from some silly stock footage illustrations of the verse, the poetry is generally handled very well. One nice move is to shoot different interviewees reading the same poem, which allows their various stresses and inflections to naturally compound the richness of the verse. This multiperspectival quality is an important theme to both Snyder’s vision and the ecological vision he incarnates. Still draws our attention, for example, to “Straits of Malacca,” from 1957, which presents three different takes on the same phenomenon, like Stevens’ blackbird rendered in the variant minimalism of Han Shan, Basho, and William Carlos Williams.

At its best, Snyder’s poetry gives us the tangible transformative moment stripped of symbolic significance or romantic frosting but sustaining its immanent flicker. More thing than thought. (For an extended meditation on this process, and its implications for memory and our relations to the non-human world, please study my favorite long Snyder poem, a shimmering meditation on Indra’s net called “Bubbs Creek Haircut.”) The film sheds direct light on this dry Zen kindling when Snyder turns to the subject of haiku, which he defines as “a precise imagistic short poem.” This is turn sets up a brilliant elaboration from Hirshfield, who describes the poetic process of “plac[ing] a flash of perception against perception in such a way that there’s almost an electric spark that jumps.” There you are, in the middle of experience, “paying close attention to specific particular objects of this world at a particular moment in time,” when “eternity flashes through.” Like a lightning strike over the crags, Snyder can still flash.

• Master of the Temple: the Tragedy of Jack Parsons

I don’t watch too many YouTube docs. Either you find yourself presented with the same old potted plants, or the dank claustrophobia of the rabbit hole closes in. But when Peter Grey, the occultist, author, and publisher, let readers of his “The Adder in the Churchyard Wall” newsletter know that he was featured in a recent film about Jack Parsons, I took the plunge. Grey has written extensively and insightfully about Golden State occultism, in his book The Two Antichrists and on the Substack, and I trust his slightly jaundiced witchy eye.

The life of Jack Parsons — rocket scientist, occult bohemian, and follower of Aleister Crowley’s religion of Thelema — is one of the mighty California Tales, a lore trip through the state’s singular technocultural landscape, and a narrative so redolent with southern California weirdness that, if it were presented as the fiction it resembles, it would seem too outlandish and overdetermined for the proper suspension of disbelief. I have written twice about Parsons, in an academic chapter that analyzes how the man navigated the liminal zone between technology and magic, and in a more speculative essay for the occult publisher Three Hands Press, a piece that looked at his relationships, both imaginal and polyamorously real, to women and the figure of the witch.

What interests me now, after we have seen the TV show and the comic book and the academic treatise, is how Parsons’ story has drifted, thickened, and emptied itself out. I first read a version of the story in 1993, in an article in the great pagan zine Green Egg. Written by Adam Walks Between Worlds, a tricksy redhead I met a few times, the article traces the Thelemic currents of Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land, a key text to the Church of All Worlds, which published Green Egg. But a brief account of the story had seen print the year before, in City of Quartz, the Marxist historian Mike Davis’ game-changing account of the sordid past and future of Los Angeles. Then, at the end of the decade, Feral House released Sex and Rockets by the pseudonymous “John Carter,” an undercooked book stuffed with rich but sometimes hasty data.

By now, after further bios and treatments, Parsons has a toe-hold in pop memory and even the obscure details of the tale are rather well mapped. Thankfully, Master of the Temple doesn’t try and stake out any new edgelord terrain. Instead, with the help of three fine interviewees, it gives a comprehensive account of Parsons’ life and work against a well-drawn backdrop of sciences both occult and explosive. Atrocity Guide, who has also made compelling videos about Zen Master Rama, Immortalists, and Breatharians, is a wizard of the archival image; I have been fascinated with Parsons for decades, and I saw lots of footage and photos that were new to me. Though this documentary proceeds with a certain humorlessness and lack of wit, the story still shines, rich with detail and the apposite image. One fact I had not known before was that, for a time, three of the four departments at the early Jet Propulsion Laboratory were led by Thelemites.

Despite the salacious draw of Parsons’ esoteric hedonism, Atrocity Guide thankfully spends more time than most would have on the scientific side of Parsons’ story — the rocket experiments in the Arroyo Seco, his development of solid fuel for the JATO program sponsored by CalTech, and the founding of JPL. In the second hour, the science fades away as we move deeper into Parsons’ magick, especially his ceremonial relationship with “scribe” L. Ron Hubbard, whom he had met at an LA science fiction club. In treating the fascinating question of how much Thelema influenced Hubbard’s later Church of Scientology, Atrocity Guide doesn’t exactly argue the case — instead, we simply watch footage of Hubbard lecturing in a way that clearly indicates that his “bridge to total freedom” was built over the very same Abyss that Parsons tried to cross towards the end of his life.

Jack had lost a lot by then, including his money, his security clearance, and probably his relationship with Marjorie Cameron (whose shrift is short in this doc). On the eve of a voyage to Mexico, Parsons died in an explosion in his own lab. Without pushing either the conspiracies or the occult coincidences too far, Atrocity Guide does rightly quotes the scriptural prophecies — “thou shalt become living flame” — that Parsons had early channeled, with L. Ron’s help, from the goddess Babalon.

No folks, you can’t make this shit up. Only California can.

• Lost Angel: The Genius of Judee Sill

I love Judee Sill’s music and have loved it since I first picked up the vinyl reissues of her two albums back in the early 2000s. I bought Judee Sill first, and I picked it out of the bin based on the cover vibe alone — a fuzzy early 70s photo of a lanky chanteuse with a heavy-duty cross necklace, and maybe a sticker mentioning Jim O’ Rourke or something. I was sold, and the even more magnificent Heart Food came soon after. For years, I knew nothing about her challenging life nor the tragic arc of her very Californian career, so sustaining and strange were these songs, which seemed to spring from some mysterious source, somehow melding cowpoke folk and baroque fugues and soulful gospel and mystic Christian revelations. Genius, for once, is the right word.

Lost Angel is a solid documentary rather than a remarkable one, and includes some annoying contemporary tics — too many animated sequences, and an over-reliance on commentary from famous fans (though luckily these include Weyes Blood, who is as collected and articulate in her thoughts as in her music). But for Sill fans, Lost Angel is required viewing. The doc unfolds her gnarly, turbulent, and ultimately tragic life — hooking, reform school, career failure, junk, early death — with plenty of archival material, but without the kind of easy sentimentality that Sill, given her own scrappy, intense, salty-dog attitude, would have rejected. The LA music scene gets a good sketch, and there are rich interviews with friends and lovers, especially with the wry J. D. Souther, the sometimes Eagles songwriter who broke Judee’s heart after taking up with Linda Ronstadt, inspiring Sill’s near-hit “Jesus was a Cross Maker.” Probably the biggest treat are many glimpses of Sill’s wonderful drawings and journal doodles, though I would have preferred a bit more archival rigor in the presentation.

My biggest beef with Lost Angel is its inability or perhaps refusal to directly address Sill’s singular religious vision, which is absolutely central to her body of work. I say religious rather than spiritual, because, while Sill drew from the proto-New Age grab-bag of astral planes and archetypes and planetary gods, the core of her sensibility is visionary Christianity transposed to a post-hippie key. Sure she was on Joni’s label, but Judee’s songs are less singer-songwriter confessions than numinous poems transmitted from her particular Angeleno cross of desire, suffering, and exile — an affective Catherine wheel that’s been rolling since the days of medieval female mystics like Julian of Norwich or Margery Kempe.

It’s often unclear whether the male figures in her songs are West Coast cowboy lovers or Jesus Christ himself, the original bridegroom offering up roses that bleed. This fusion of God and eros was the staple of soul music, of course, but Sill articulates the crux in a deeply singular key that nonetheless touches the timeless. In songs like “The Lamb Ran Away with the Crown,” she combines religious images — serpent, spark, lamb, crown, demon, battleground — in such a fresh way that the tune seems like a new revelation of some ancient drama. Other songs are so intimate in their holy yearning that they seep into you and shape your very capacity to really hear them in the first place. That’s what live spiritual texts do for you, whether poems, films, ballads, or sunsets: they make you recognize their forms and feelings as shapes of your own being, tripping over itself as through a tangled veil.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. More than anything, I want to resonate with readers out there. So if you want to show support, the best thing is to forward my posts to friends or colleagues. You are also welcome to consider a paid subscription, and you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

Baldwin, Belson, Snyder & Sills = Best Burning Shore yet!

Oh man, this check-in with ATA warms the heart so much—especially your impression of its analog heart in what I assume is a pretty chilly post-boom Valencia. And this: “…the world that one has known — in this case the world of the analog underground — disappears at about the same rate that the actual people you have known and loved disappear, whether they drift away, go nuts, give up, or die.” Oof. Vital work here.