Camera Trips

The Burning Shore, no. 3

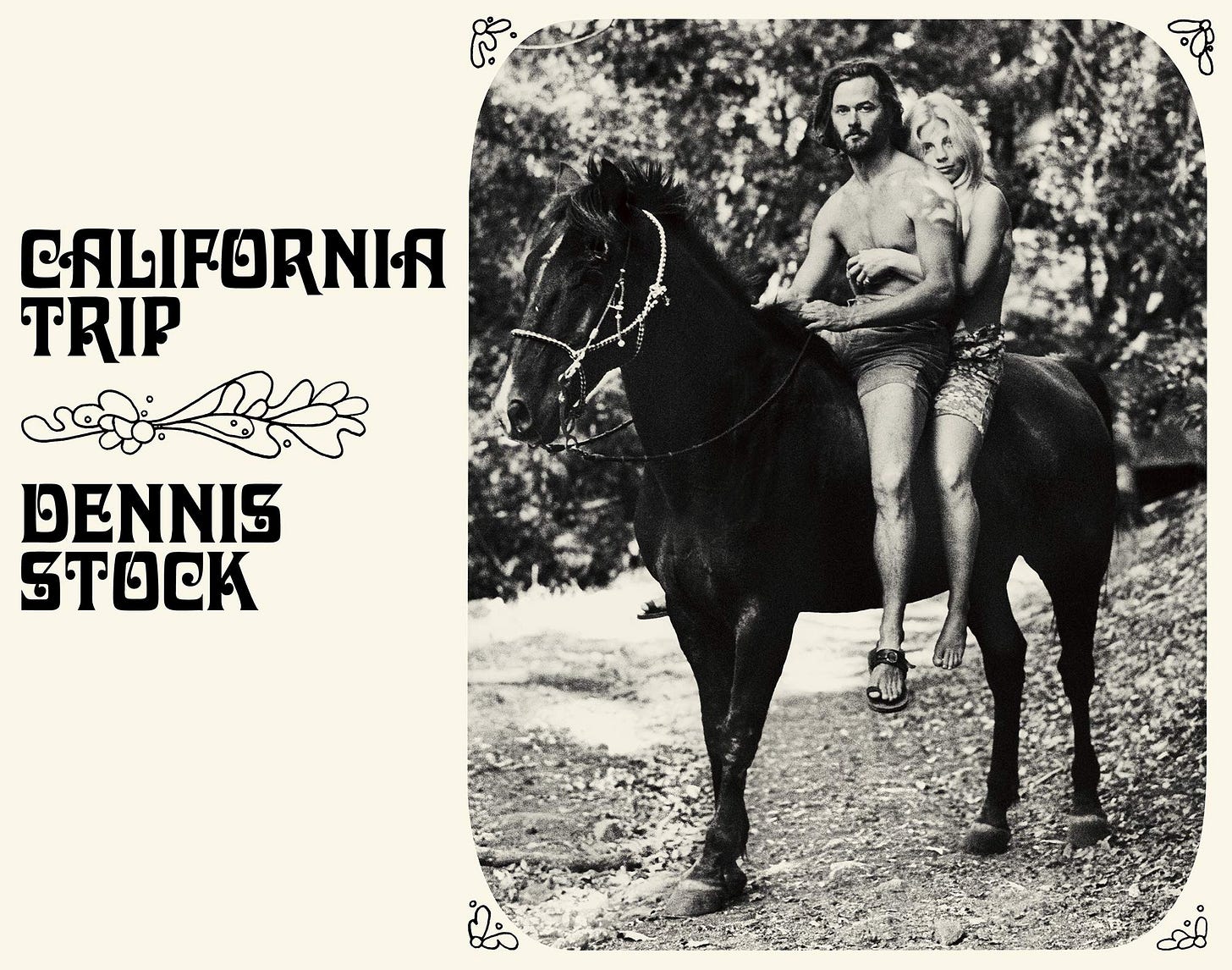

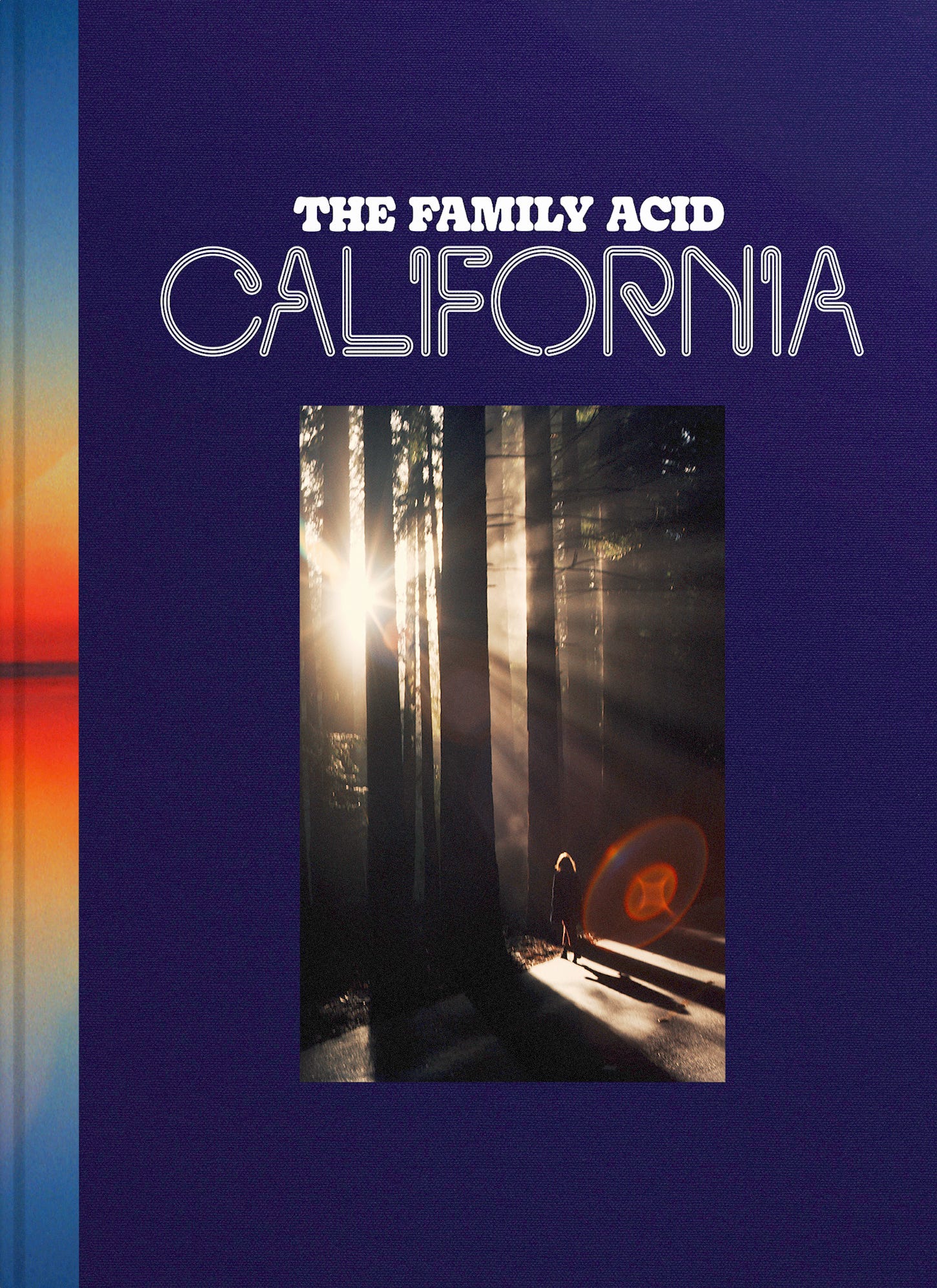

Last year, two remarkable photography books appeared, both of which document, in an appropriately twisty fashion, the California of the late 60s and 1970s. One is a delightful reprint of a 1970 classic, Magum photographer Dennis Stock’s black-and-white California Trip, returned to the world by the fine folks over at Anthology Editions. The other is The Family Acid: California (Ozma), packed with colorful Kodochrome slides and prints, often with multiple images per page, but still only representing a smidgen of the vast personal archive shot by actor, reggae historian, and longtime Angeleno acidhead Roger Steffens.

Both books represent restless and roving trawls though the towns, beaches, and backlots of a state whose unplanned surrealism bloomed back then as reliably as apocalyptic sunsets. But for all their shared concerns with mind-bending juxtapositions, human comedy, and the hedonic arcana of California subculture, profound differences animate these two works. One is a work of love; the other, something perhaps closer to fear.

For Roger Steffens, taking photos was a seamless part of a creative and unorthodox life that led him around the state—Death Valley, Big Sur, Echo Park, Sausalito—without ruining his capacity for grounded engagement. In 2013, Steffens’ kids Kate and Devon started scanning his slides and negatives and posting them on Instagram under the name the Family Acid. The feed blew up, and it’s not hard to see why. Steffens combines a photo-journalist’s instinct for the “grab shot” (a technique picked up from his photographer pal and fellow Nam vet Tim Page) with an extrovert’s nose for the happening and a tripper’s eye for leering colors and furtive easter eggs of significance. A balloon blazes as it briefly eclipses the sun near Hippie Hill. Butt-cheeks poke through rips in embroidered bluejeans in Mendocino. Little black boys, one holding a skateboard, seem to spill out of an Ethiopian mural in South Los Angeles. Lotsa shots of cannabis leaves, funky cars, cliffsides, billboards. “Traveling Cosmic Energy Shows.” “Gas Cheaper than LSD.”

Occasionally we are reminded of melancholy and strife. Cops cuff a longhair on a ripped-up Telegraph Avenue; Nam vet and activist Ron Kovic, a good friend of Steffens, stares stricken from his wheelchair into the Mendo midafternoon. But The Family Acid: California is in essence an extended lark, our photographer an imperturbably cheery head, reefered and Rastafaried and in love with his friends and family and the scattershot and beautiful place they called home. These are improvised and intimate pleasures, not products or portents. When they bring us pleasure, we are part of the family.

Steffens’s use of multiple exposures is perhaps the key gesture here. The decision to re-expose film is a dice throw, an act of faith in the playfulness of multiple perspectives and the value of subjecting an already captured image to the serendipity of leaps through time. Such images are also, of course, hallucinatory, and some of Steffens’ are trippy as shit. They not only recall the formal and symbolic palimpsests of psychedelic vision, but loop the question of the photographic object back into the eye of the beholder: seeing these impossible scenes, we glimpse our own seeing, our own congealing of reality from the virtual.

Other Family Acid images feature artifacts like diffraction spikes, iridescent orbs, and weird lensing effects. (Check out the cover shot up top, which juxtaposes the classic clerestory light of redwood groves with a mandalic UFO flare.) These are special effects, my friends, evidence of that hippie will to hack media tech in the quest for unusual experiences. They also recall the more sacred lights you can only chance upon, in the strangest of places if you look at em right, those wink-wink psychedelic glimmers that occasionally illuminate parking lots, or crumpled beer cans, or goofball commercial signage—Phil Dick’s “trash stratum,” temporarily kindled into something high and holy and wholly profane.

Are such moments of grace inside or outside that blazing eye of the beholder? There’s another California koan for you. In the book’s dedication, Steffens quotes Tim Leary describing SoCal as

the growing edge of the human species…where the migrants and the mutants, and the future people come, the end point of terrestrial migration.

There is too much to unpack in Leary’s claim, matters both dizzying and deluded, and perhaps we will return to agent Tim down the road somewhere. For his part, Steffens thinks his description well fits “this entire visionary state we call home,” and though I ultimately have a more ambivalent take on it, I’d have to agree. This is, after all, the same pun I used in titling the picture book on California religion I made with the photographer Michael Rauner over a decade ago. California: a place of manifest novelty that is also an expanded, and sometimes deranged, state of mind.

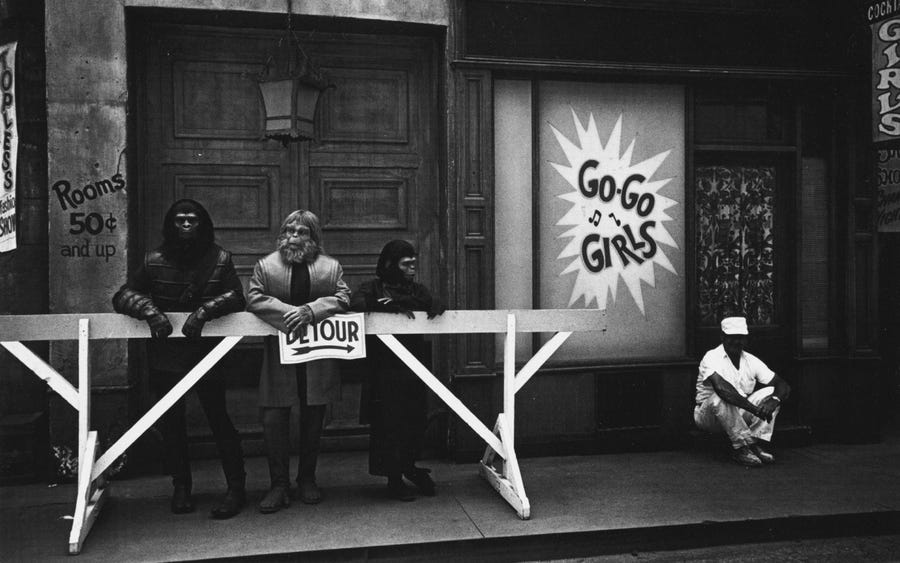

Visionary states are also pretty compelling places to visit. Dennis Stock, the East Coast pro who captured that famous image of James Dean smoking in the rain, made his trip in 1968, recording the 100 images in California Trip over a mere five weeks. In contrast to the scrapbook layout of The Family Acid: California, which features overlapping images and full bleeds, California Trip is shaped by the art gallery: one image per page, surrounded by white space, the pairing of each spread carefully controlled. Still, despite their important differences, Stock’s book travels the same general spaceways as The Family Acid: California, both photographers sharing an eye for pop surrealism, for sun worship and psychoactive folkways, for masks and signage and kooky architecture.

Both a formalist and a journalist, as befits his membership in the Magnum cooperative, Stock excels at roping together disparate elements that, to quote Ginsberg’s North Beach howl, “made incarnate gaps in Time & Space through images juxtaposed.” A nude bottle-cradling toddler careens past a Hells Angel on a lawn. Ruined crash-test dummies huddle in a car covered with “Fallout Shelter” signs. A garden store employee lugs two meditating lawn buddhas by their chins. Or these two home runs:

Such weird moments of reality-as-collage are not the principal reason that California Trip found its way back to print however. As Anthology notes in their online copy, the book “became an emblem of the free love movement that continued to inspire throughout the decades.” This is what first stood out for me: the surfers, the multi-racial heads, the Jesus Freak graffiti on the back of a VW bug—plus the only interior shot I’ve ever seen of Mystic Arts World, the psychedelic venue opened by the acid-slinging Brotherhood of Eternal Love in Laguna Beach. But Stock was not covering the counterculture, let alone expressing its vibes from the inside, as Steffens does. Instead he was cataloging the freaks and flower children as simply further symptoms of a larger and more ominously infectious condition: California.

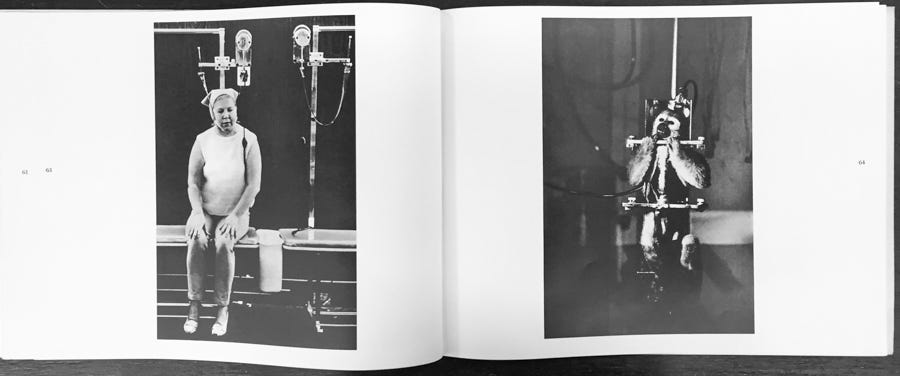

After all, less than a quarter of Stock’s pictures capture the youth culture of 1968. We also get cowboys, old dudes playing bocce ball, classic car buffs, pawn shops, pet headstones. Quite a number of images record the technological factor in the Cali equation: a deep-space dish antenna poking through the Mojave air, a Titan II missile displayed at a Sacramento fair, a pair of Vandenberg AFB workers in protective onesies. One particularly creepy shot from a lab at SRI (the Stanford Research Institute) features a research monkey squirming against the creepy apparatus that confines him. Across the gutter we find a formally similar image of a middle-aged lady on a gurney in Encino, her head attached to a strange medical apparatus.

Through this particular juxtaposition, Stock also reveals the jaundice in his eye, or at least the disinterestedness lurking behind his seemingly playful and surreal approach. These images are specimens and portents; a sardonic anthropologist’s report back to the imperial center about the exotic and potentially dangerous periphery. He makes this stance clear in the short preface to the book, which rattled me when I finally got around to reading it in preparation for this piece. He speaks of first visiting California as a young man, with “traditional concerns for a spiritual and aesthetic order,” and finding that the state’s air of unreality “projected chaos.” Returning in ’68, he discovered something more like a messy R&D workshop.

Every idea that Western man explores in his purusit of the best of all possible worlds will be searched at the head lab—California. Technological and spiritual quests vibrate throughout the state, intermingling, often creating the ethereal. It is from this freewheeling potpourri of search that the momentary ensembles in space spring, presenting to the photographer his surrealistic image. However, to Californians it is all so ordinary, almost mundane. The sensibility of these conditioned victims is where it is all at…

Nailed! For though I was a tyke in 1968, these images are, if not quite ordinary, then deeply familiar, their stark absurdity and wayward drift not only charming but cozy. Ah, my wacky-ass home. And in one case, literally home: one shot of a VW hurtling down a highway towards a crowded beach was snatched at the southern edge of my home town of Del Mar, where the brackish waters of the Los Peñasquitos Lagoon spill into the sea along Torrey Pines state beach.

But it’s Stock’s “conditioned victims” line that really hit me. One reason is that I am rereading Gravitys Rainbow right now, and am more sensitive that usual to those old proverbs for paranoids. Pynchon, who was living in a ground-floor apartment in Manhattan Beach when he wrote the Rainbow, also tracked that California collision of technology and esoteric quests in his conspiratorial The Crying of Lot 49. As I am currently rediscovering, Pynchon’s work was deeply influential on me. It helped me eventually forge my first great topic—Techgnosis—and it continues to mark my work, which is largely focalized through a paranoid-critical California lens. And the longer I study the place, the darker and more tangled its complexities becomes, complexities that The Burning Shore is partly designed to unpack. And one of these tangles involves the dance between countercultural energies and the forces of conditioning and control—a twisted tango that cannot help but implicate my own subjectivity.

Rats in the head lab we may be, but we are also human beings—those “viable, elastic organism[s]” that, in the immortal words of PKD, “can bounce back, absorb, and deal with the new.” (And, as Steffens reminds us, we can also have a blast doing so.) But Stock shows little of Dick’s empathy for the Californians he shoots, who are generally caught out in some private moment of random weirdness. Breaking the humanistic ethos of photo-journalism, most of the people in his images are turned away from us, their faces obstructed, cloaked by shadows or masks or newspapers.

But where is Stock—or as he calls himself, “the photographer”—in this story? No conditioning here folks! Just that pure and disembodied gimlet eye…Indeed, the only time Stock shows himself in California Trip, it is with a driver’s-side shot of his bespectacled eyes staring off from the rear-view mirror: a frame in a frame in a frame, the formalist “meta” rather than the embodied and social loop-de-loop of Steffens’ playful psychedelia. Stock is a modernist in a postmodern land, clutching at ironic reference points, still terrified of the chaos that, engineered or not—and most likely both—others were learning to surf.

—Erik Davis

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of the Burning Shore. This publication is my attempt to write directly for readers without worrying about anyone else’s editorial agenda. Subscriptions are free, though I may eventually create paid-subscriber-only content. That said, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription.