Fire Doctor

The Burning Shore, no. 6

The nature of poisoning by Rhus has always partaken somewhat of the mysterious, and it has been the subject of much speculation.

— H.W. Felter, The Eclectic Materia Medica (1922)

I SHOULD HAVE seen it coming. There I was on one of my trail walks, strolling through the svelte mecha shadow of Sutro Tower, that candy-cane Shiva trident that’s been flinging signals across the Bay since the seventies. I emerged from beneath a bank of gum trees, and froze before the sight: a massive stand of poison oak, the young, plump, viperous leaves already taking on the ruddy hues that will ripen into a sunset blaze by late summer, making a sweet Berkshire fall out of our bane. The mighty shrubs stood open and exposed, fearless even, as if daring me to jump into their folds, or simply to run a finger along the pointy margins of their leaves. But what stopped me in my tracks was not an urge from the imp of the perverse, or the more reasonable paranoia of proximity. What stopped me was a gut punch of awe: an almost idolatrous humility before the fierce presence and implacable power of these fierce plants.

“Hi guys,” I mumbled, trying to keep things light. And then moved on.

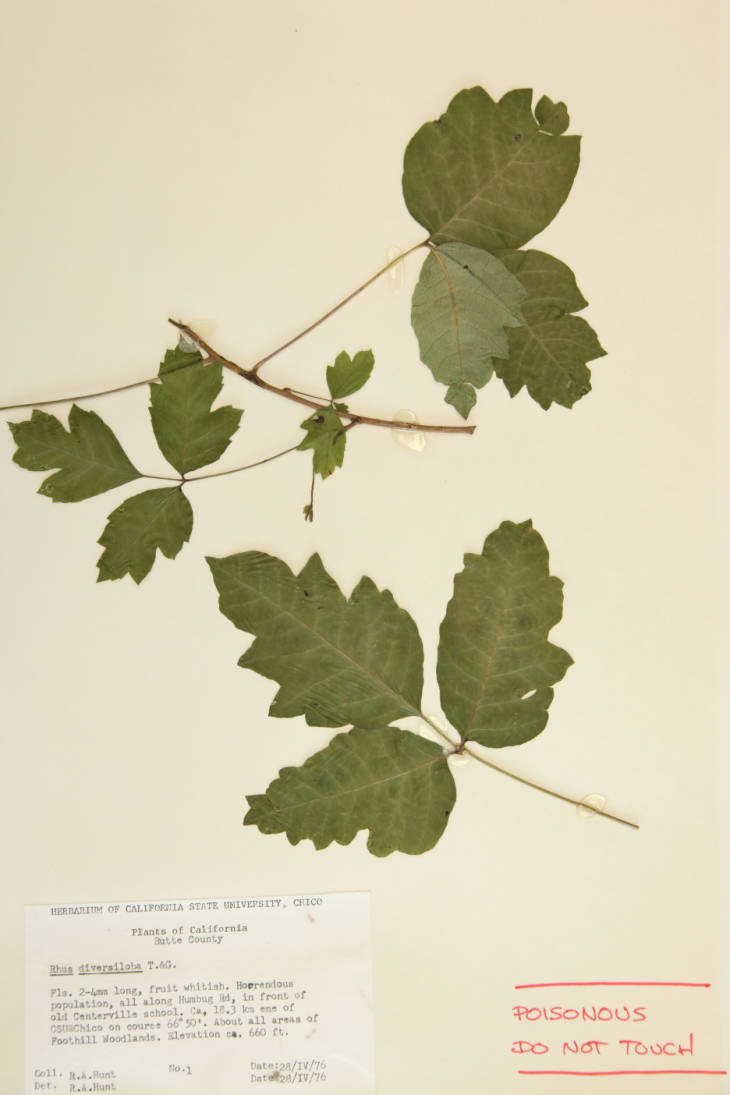

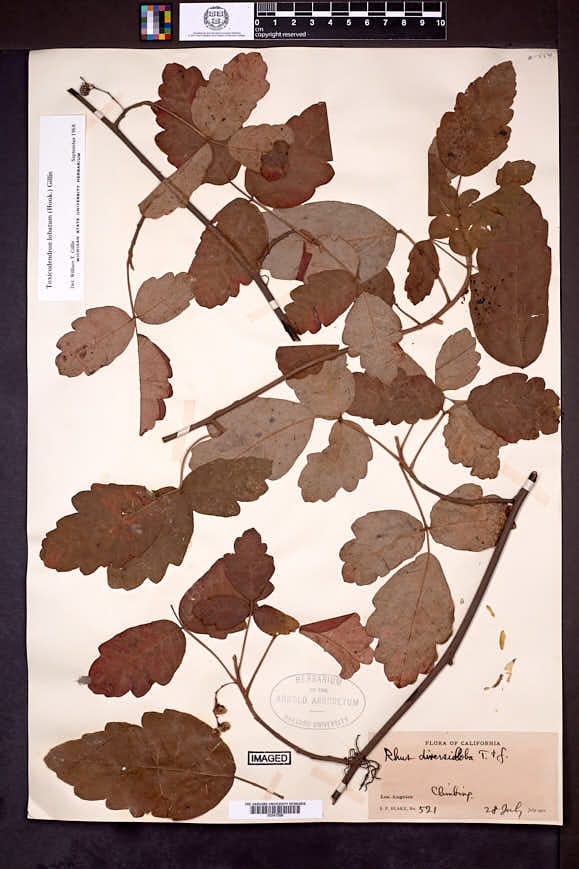

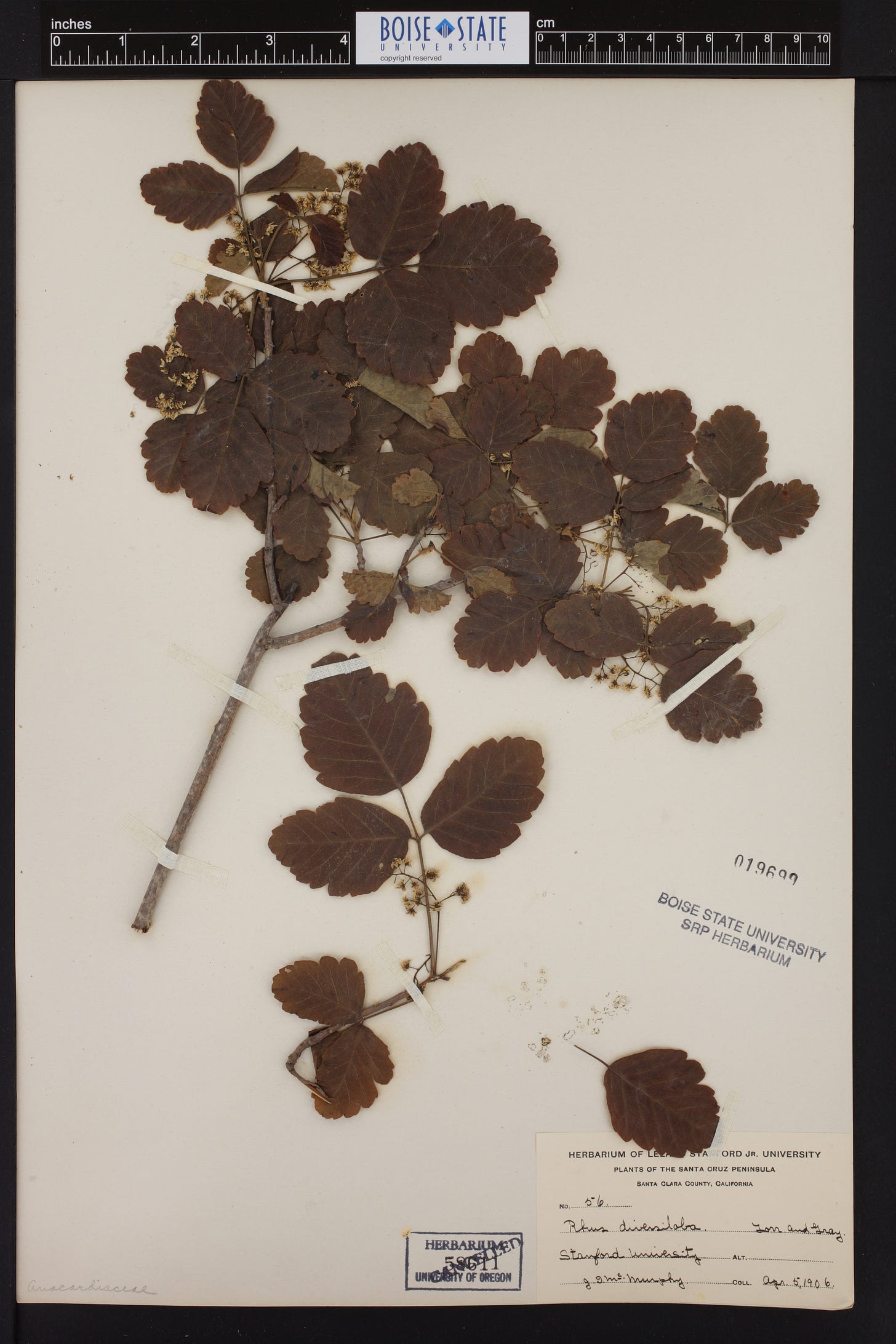

One of the fun things about The Burning Shore is that new ideas for columns keep popping into my head. And here was another one: poison oak, Toxicodendron diversilobum. This mighty and dangerous plant is found all along the West Coast, and is kissing cousins with the poison ivy and eastern poison oak that cloak much of the rest of the United States. But T. diversilobum—formerly Rhus diversiloba—is densest by far in California, where it remains at once the most widespread shrub and, pound for workers-comp pound, the most hazardous plant. My pal Fletcher Tucker, backcountry guide and wildcrafting musician, thinks they should put it on the state flag.

So I filed the topic away in my Burning Shore folder and went about other research. A week later, I drove up to visit an ethnobotanist I know in West County, Sonoma. We went crashing through a creek near his home with some friends and his wife, son, and older daughter. It was a groovy hippyish time, deeply nourishing in this shut-in summer of confusion and dread. The cool, snaky stream followed the edge of what was once Miwok territory, but it was probably a Pomo place; sure enough, Shannon found a sweet piece of worked obsidian. His younger sister pounced on a squiggling newt, while, in a mildly stoned revery, I admired the goofy sport of water striders. The water was delicious and bracing for those of us who plunged.

It was primo oak territory, of course, and I kept my eye out as I have for years. Like a lot of folks, I was seemingly immune to the stuff for decades, until I had a couple of massive and excruciating break-outs in my thirties. But since then, things have been pretty mellow. I love bushwhacking and stream walking, so I take my chances, but except for an occasional crop of stinging pimples, and one ankle rash that bubbled up bad in the central valley heat a few years ago, it felt like the oak and I had reached a certain understanding. A kind of mutual respect. In my magical thinking—and part of my motive here is that magical thinking is endemic to the oak encounter—I was over the hump.

You can see where this is going. A few days after the stream walk my crotch started to itch, and within a few more the old miseries were aborning. The contagion unfolded across my body over the following ten days or so like an evil wizard plague, distributing pebbled rashes, raw swellings, weeping pustules, vesicles, urticaria, and the occasional Mt. Shasta solo boil anarchically across my body—left armpit, right midriff, left inner thigh, right palm, chest, right outer thigh, neck, right ankle, even a touch on my junk. An astrologer might have divined some meaning from this constellation, but it made no sense to me.

Poison oak isn’t actually poisonous (nor is it an oak). It contains an exceptionally potent resin, urushiol, which is shared by a number of plants in the Anacardiaceae family—which includes mangos, cashews, and the Asian lacquer tree, whose Japanese name, urushi, lends urushiol its exotic tang of a name. Most humans and some primates are highly allergic to the stuff. In general, the contact dermatitis that results from exposure to urushiol is limited to a vexatious if sometimes incapacitating drag-and-a-half. But there are real dangers as well: sepsis can set in, your eyelids can swell shut, you can scar bad. If you inhale the burnt particles or vaporized oils, which firefighters do every year, you can wind up in the ER, pumped full of hardcore corticosteroids. Occasionally folks wind up dead.

But enough of science, let us speak of pain—or rather of the pleasure, which is what one rural couple I know call the oak discomforts that continue to vex them despite great care and years of removal efforts. The pleasure is a singular suffering. Like a fine perfume, it blends a variety of notes into an evocative medley whose torment is greater than the sum of its parts. These parts include intense itching, and therefore intense and frustrated temptation; a bouquet of pains (pinpoint stabs, dull throbs, larval tunnelings, crispy sizzles, electric arcs of flame); sleeplessness and constant psychic irritation; and repulsive carnality, as one confronts an almost Sci-Fi range of body horrors that can include elephant-man patches, split ruby skin, ominous swellings, all manner of leprous lesions, and yellowish discharges that soak clothes and bedsheets and curdle into a bilious crust. Perhaps most insidious of all is the slow but relentless rate of attack and decline, as symptoms unfold and linger like the well-savored punishments of an unhurried torturer.

There is only one enjoyment to be reaped from these inflictions, at least in my experience: the almost perverse relief produced by submitting the flesh to hot showers and baths—with or without oatmeal, mugwort, and other additions to the water. Some dermatologists argue against hot water, which can further inflame skin and spread oils early on. But the secret is out: performing what your fingernails dare not, the hot water drives the positive feedback loop of itching and scratching into an orgasmic, almost sado-masochistic rush that I can feel all the way down to my toes. This flush—along with topical creams and moisturizers, natch—is followed by a good few hours of respite, as if the histamines have shot their wad and need to roll over and watch TV or something.

In my world, this is one of the infernal gifts of the oak: a brief, scalding ecstasy like no other. The rush is a concrete experience of jouissance, a key psychological notion first articulated by Jacques Lacan. Jouissance is enjoyment beyond the pleasure principle, a painful but attractive excess that transgresses the boundaries that normally regulate our kicks. It is the tickle that, as Lacan memorably put it, “ends with a blaze of petrol.” Such twisted rapture is the pleasure within the pleasure, and the only one to be had.

TODAY WE HEAR a lot of talk about plant teachers. What could such a thing be? Many traditional indigenous folk hold that plants, like animals and geographical features, are “other-than-human persons” that demand and deserve reciprocal relationships of obligation, respect, and tutelage. Even an urban weirdo like me can see the wisdom of these ways, which as botanists like Robin Wall Kimmerer and Monica Gagliano suggest, can exist alongside scientific practices and biological understanding. After all, as a number of biologists now argue, plants are intelligent—they make choices, they remember, they communicate and exchange resources with other beings. If so, then the animistic experience of the world can be seen as a kind of imaginal interface: a virtual theater of presences and interactive encounters that bodies forth our embeddedness in an ingenious biological world.

Plant teachers has also become pop stars of late. A generalized, neoshamanic idea of “plant teacher” has grown alongside the explosion of mainstream interest in (and sometimes decriminalization of) psychedelic plants and fungi like psilocybin mushrooms, ayahuasca, San Pedro, Salvia divinorum, acacia, Hawaiian baby woodrose, Syrian rue, even good old cannabis. These are the big teachers of psychoactive spirituality, offering upper-level seminars in the Mystery. But there are also scores of floral tutors with milder curricula as well—the sort of teachings found in flower essences, healing unguents, fragrance oils, incense, and milder psychoactives like mugwort, calamus root, blue lotus, kava, or tea.

But please: do not allow contemporary psychedelic hype, or the mildness of many of these substances, to distract you from the infernal dimension of plant tutelage. As the plant poet Dale Pendell showed us in his magisterial Pharmacopoeia books, psychoactive education is a “Poison Path”—requiring not only the tricky Paracelsian art of dosage, but fraught experiments that can sometimes occasion pain, delirium, trauma, nausea, obsession, and acute toxicity.

What would it mean to see T. diversilobum as a plant teacher? Certainly its poison provides an unforgettable trip—a veritable spiritual ordeal, lemme tell ya, jouissance or no jouissance. But the real teachings lie in the qualities of relationship that the plant demands, which include attention, knowledge, and respect. You may not give a fig about identifying native California fauna, but you better learn to recognize the oak.

This isn’t always easy, however. Along with its effects, and the remedies for those effects, poison oak is possessed of a certain morphological ambiguity. Writing about poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) a few decades ago, the botanist Edward Frankel describes a “most perplexingly variable species,” an errancy that also characterizes its westward oak cousin. Poison oak’s species name—diversilobum—announces the extreme diversity of its leaves, whose color, size, patterned edges, and even number can vary significantly. “Leaves of three, let it be,” goes the mnemonic, but oak can have five and even seven leaflets (sometimes on the same stem as the usual three). T. diversilobum also grows in many different habitats, and shapes itself to that diversity. As a certain Dr. Kellogg noted in the San Francisco Pacific in the early 1850s, poison oak

is wonderfully changed in general appearance by its locality; when flourishing near trees, it becomes all at once very aspiring, and the self-same obscure growth elsewhere, is transformed, as if by the enchanter’s wand into a slender creeping vine climbing to the tops of the tallest trees.

Oak can grow into a stout tree, a shrub, a climbing vine, an aerial creeper. (Just check out its range of costumery here.) In the gum forests near me in San Francisco, it often hides, sneaky-cheeky, within banks of the similarly toothy and three-leafleted wild blackberry.

Another dimension of the oak mystery has to do with what one botanist called “the vagaries of susceptibility.” As noted, many of us suddenly switch from a lifetime of seeming immunity to utter sensitivity. But the acute rashes that result can, in some cases, be followed by a later drop-off in susceptibility. (This is the category I had fantasized I was in.) Then there is the vexed matter of hyposensitization. People I know claim to have reduced or even eliminated their sensitivity by eating small spring leaves of the oak—a practice also popular among many indigenous Californians—or by drinking the milk of goats who ate the stuff. But following a boatload of inconclusive studies in the mid-twentieth century, these claims are rejected in most of the official literature—partly, one suspects, because the mechanism of such desensitization, as with so many immune system puzzles, simply sets up another enigma.

Then there are more circumstantial vagaries. Sometimes you crash right into a thick shrub like a doofus and nothing happens down the road. Other times, you seem to barely catch a glimpse of the stuff out of the corner of your eye and wham-o—the pleasure. Kellogg, back in the nineteenth century, reports that some people break out in rashes simply by coming “within the sphere of this shrub, without touching it.” He also insists that outbreaks can reoccur months and even years later in individuals “far remote from all exhalations of the plant.” Such anecdotes, also officially denied, echo down through the itchy ages. I have heard them myself.

Perhaps it’s just a matter of luck, a roll of the poison dice. None of my West County creek-walk pals, many of whom were oak sensitive, got anything more than a pimple or two after our hike, and one commented on what he perceived as my care around the young leaves. I was certainly being as vigilant as possible, but when I review the day, I do recall one lapse, when the luminous loveliness of the morning induced a brief swoon as I carefully picked my way streamside. When I came to, mere seconds later, I realized that pale and creamy lotus leaves shimmering before me like a veil were, shake it off now soldier, the dreaded oak.

But why did such a brief brush produce such terrible results after fifteen years of similar California bushwhacking? Urushiol resin is tenacious stuff, to be sure, and fully binds itself to the skin within an hour. But the scattershot distribution of the rash across my body remains hard to square with the idea, still insisted on by many doctors and websites, that the dermatitis results solely from direct contact with the oil. I suppose I could I have picked at my armpit with my dosed fingers, or, I dunno, rubbed my sneakers on my inner thigh just for kicks. But it sure seemed like my body was undergoing a systemic response, an expressive immune system jam rather that a rote billiard-ball reaction. Some lesions even popped up in the same hotspots that have been afflicted in the past, as if expressing some weird kind of allergic memory.

So I was pleased to stumble across the following admission in a recent nursing journal:

Cutaneous contact with urushiol can lead to autoeczematization (also called an id reaction), with dozens of red papules and vesicles on the trunk and extremities. This is frequently referred to as a systemic reaction because the sensitized white bloodcells are thought to travel to other areas of skin, causing an itchy rash in places where there was no skin contact with urushiol.

Mystery solved! It’s autoeczematization, or even better yet, the id reaction, which seems an even better name for ugly surface symptoms that emerge from the depths, rather than from any direct external trigger. But while the story about vagabond white bloodcells is nifty, it is only that: a tale. Dig down, and you discover that the id reaction is “not fully understood.” And when things aren’t understood, or when they behave in ambiguous or tricksy ways, this feeds the growth, and even reasonableness, of relational animism. Rationalists don’t want to admit it, but sometimes magical thinking is the most pragmatic avenue at hand.

SO WHAT KIND of plant teacher is T. diversilobum, what manner of vegetal sage? My wife, who is terribly sensitive, thinks the oak is evil and should be expunged from the universe. I am not down with such demonism. Nor was the loudmouthed Captain Smith, of Jamestown and Pocahontas fame, who was the first whitey on American soil to describe poison ivy. After enumerating its painful but ultimately superficial effects, he admits that “It hath got itself an ill name, although questionless of no ill nature.”

But what is that nature then? Some California plant folks like to call the shrub guardian oak. The idea is that, because it is only noxious to humans—with a special bead on settler-colonialists, perhaps—the oak guards and maintains space for other-than-human beings. The oak is a pioneer species, after all, moving readily into disturbed land, where it provides food and shelter for all manner of critters while keeping two-legs at bay. Such guardianship can also be seen as kind of spiritual stance, not unlike the protector spirits that Tantric Buddhism names Dharmapalas: wrathful deities that safeguard the dharma.

For the wilderness vagabond Fletcher Tucker, a native Californian I know who offers prayers to the oak but still gets stung sometimes (and favors fresh mugwort in his healing baths), the fierce guardian teaches humility. “Maybe you don’t get to scramble down that hillside or jump into that pool. Just stop for a second and look at the beautiful view. Maybe that’s all you get.” Another homegrown Californian plant person I know, an expert in native flora, argues for the feminine face of the plant—the supple, curving spring branch that strokes you with a soft delicious caress. I think the oak is maybe genderqueer.

And what about the herbalists? In his forthcoming magnum opus, Arcana Viridia (“The Green Mysteries”), the poison pathworker Daniel Schulke—a California-based folk herbalist and head of the magical order Cultus Sabbati—provides some esoteric correspondences for T. diversilobum. Associating the oak with Mars and the element of Fire, Schulke suggests that its central powers are defense and harassment. He names its spiritual essence contagion—making it a fit emblem for our times—and aligns it with the alchemical procedure known as deflagration, which occurs when a material—usually touched with saltpeter—is tossed into the hot crucible, where it burns like gunpowder.

Schulke’s peppery divinations are confirmed in part by the Pomo folks who once lived around that same Sonoma creek where I got schooled. They called (and call) poison oak Ma-ta-yä”-ho, which is parsed by V.K. Chestnut, in Plants Used by the Indians of Mendocino County, California (1902), as Southern Fire Doctor. Pragmatically, this name may represent the medicinal use of oak to burn out and remove warts and ringworm (though doctor also suggests an other-than-human shaman). The Chumash similarly used the sap to cauterize wounds, while one Wailaki fellow from up near the Eel river told Chestnut that fresh oak leaves, quickly bound to the wound, were good for snake bite. All these uses, however, should not lure us into the old folk belief that Indians were naturally immune. Many tribes recognized T. diversilobum as poisonous, and offered many remedies in turn. Gumplant, a native daisy, was used to treat the inflammation, and today serves as the main ingredient in the over-the-counter medication Tecnu Extreme.

California Indians had a number of non-medical uses for poison oak as well. The Concow mixed its leaves into acorn meal, while the Karok used its stalks to spit salmon steaks for smoking. Some tribes used—and maybe still use—the deep oils of the roots to blacken strands for basketry or textiles, while the burnt remains of the same roots yielded good charcoal to poke into the skin for long-lasting tattoos. (Reportedly, some Pomo Indians also used these ashes to darken the skins of children with mixed blood.) But the weirdest traditional use I found was suggested by a brief line in an online ethnobotanical database. Apparently some Karok chewed the plant like tobacco—as one informant put it, “just to raise heck.”

As always, its vital to acknowledge that these plant ways continue today. In her book Healing With Medicinal Plants of the West (2009), written with James D. Adams, Jr., the remarkable Chumash healer and spiritual leader Cecilia Garcia wrote that eating the leaves can not only prevent the oak rash but can cure skin infections in general, including the venereal disease sores that first came with the Spanish. Garcia, who died in 2012, also used the oak with Vietnam vets who came back from the war in shock. “A tea of the leaves was used to make them vomit and wake them up. Then they were alive again."

Even Anglo-Americans treated poison oak and ivy as medicines, at least in the past. American Eclectic healers, who were inspired by Native American plant medicine, used the plant—sometimes even internally—for its “irritant, stimulant, and narcotic properties.” But the real settler magic lay with the myriad of remedies conjured by hook or by crook. Dr. Kellogg’s suggestions, from the 1850s again, include “sugar of lead” in water; cotton batts, “one side dipped in elder-flower tea, or in fresh blood;” and iodine splashed into an ounce of alcohol and “applied with a feather.” Other folks used corrosive sublimate, or gunpowder, or lye, or booze, or the classic oatmeal bath. Harvey Felter’s Eclectic Materia Medica provides a poem of possibilities:

lobelia (infusion), veratrum, gelsemium, hamamelis, grindelia, stramonium, eupatorium, serpentaria, lindera, sassafras bark, dulcamara, oak bark, tannic acid, alnus (boiled in buttermilk), carbolized olive oil, sodium bicarbonate, borax, alum curd, and solution of ferrous sulphate (green vitriol).

The one remedy I found closest to my own heart is the suggestion of a miner writing into Hutchings’ California Magazine in 1857 under the nom de plume Gold Spring. He suffered terribly from the oak in the goldfields, and tried everything, even the most violent methods. Still, he concludes, “I am inclined to the opinion that, when convenient, frequent bathings with water, as hot as can be borne, is about the best treatment.” That might be about the best you get.

Humility, attention, fear, mystery, luck, even jouissance: poison oak teaches all these and more, whether you want it to or not. It chastens our humanist hubris, and, for the budding animists among us, demands we respect the poison that is always at play in the poison path. I cannot speak for other places, as I am just a local boy, but it remains an essential plant master of these California climes. As Dr. Kellogg wrote, “to avoid it, is impossible, for it is ever-present along our path; not to know it, is both dangerous to ourselves and others.” Dangerous, yes, but also wondrous.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of The Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or pass it along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

This comment has little to do with FireDoctor which was a delight to read as someone who grew up traipsing the hills above Redwood City and then Los Altos and has trekked through every California terrain from Fresno to Arcata. Also really enjoyed Ishi's cave whose biography weirdly showed up again the next day in an audiobook called An Indigenous Peoples History of the United States.

2 questions: 1) Where, when or what exactly is the subscribers only material?

2)Will you still be writing about Gravity's Rainbow as you mentioned a few times?

Hi Joseph. 1) The subscriber-only content refers to paid subscribers. Its an annoyance of language, since if you just have the free subscription you are also...a subscriber. If you paid for a sub—thanks!—you should have received a post with a link to an audio recording of "Fire Doctor." More audio recordings will be spilling out over the months.

2) One of today's tasks is to transform all the passages marked by the dozens of multi-colored note flags in my Viking edition into digital text, so that I can start working towards a piece. I have half a dozen little pieces cooking now, and it's never clear which one will rise to the top.

Thanks for asking!