Grateful and Great Empty

Plus News & Notes

Things continue to be crunchy as we hurtle toward year’s end. Here is a brief November round-up of events, links, and reviews. In the next post, I will reveal more about the book I have been working on, whose first draft I hope to complete by the end of the year. As always, this reading experience may be more pleasant on the website—just click the title of the post above. — Erik

Upcoming Events

(•) The Dharmanaut Circle

I am happy to report that the online Dharmanaut Circle I started earlier this year (with help from some terrific volunteers) is going well, and you are invited to the next one on Sunday November 7, at 6pm PT. Again, the Circle is a monthly online meditation and conversation space for Buddhist psychonauts, experimental yogis, and mutant visionaries who dig my style. This Sunday we will work with the portal of sound. I will also record the talk and meditation—the Q&A will not be captured—and post them on the DC Youtube page which you can check out later. Follow this link to register for the upcoming circle. Suggested donation $33.

Links

(•) Warp Earth Catalog

The venerable Warp Records has been running a series of conceptual mixtapes they call “earth catalogs.” My friends over at Strange Attractor Press did Issue 10, and I was chuffed, as they say—they being British people, and occasionally Anglophiles like me—that Warp approached me to do the following catalog. As is so often the case, my list of recordings, videos, conversations, and long reads took a lot longer to gather and refine than I expected, but I am unusually satisfied with the results, which include classic links and new discoveries that largely cluster around the theme of California esoterica. Enjoy Earth Catalog Issue 11!

(•) Distended Animation

Every third post on Burning Shore is an edition of “Ask Dr. D,” a letters column I write for paid subscribers only. If you want to support Burning Shore and/or post a question, please don’t hesitate. I have a backlog to work through but it’s always nice to have freshies.

Sometimes my answers turn into dense listicles, which feel like they deserve a wider audience. After the last edition, which included my response to a question about abstract animation and avant-garde trip films, my long-time colleague and friend Josh Glenn, who writes cool books and edits the excellent cultural criticism site HiLoBrow, asked if he could break up the list and run it as a series on his website (which is big on series). I thought it was a terrific idea. The first post is on Scott Bartlett’s “OffOn” — a 1968 masterpiece which I had not even heard of before I got the question for Dr. D. There’s no escaping beginner’s mind!

(•) Camera Trips

Lucid News, which was been kindly re-running some of my Burning Shore columns, just posted one of the first pieces I wrote for this Substack, a review of two very different books of visionary photography largely focused on California’s subcultural fringe. The image of Del Mar below, from the Anthology Editions re-issue of Dennis Stock’s surreal and ascerbic California Trip, was particularly significant for me. The second my eyes fell on it I recognized the spot, since I moved to the town when I was a toddler and spent most of my adolescence there. Enjoying these images, and those from Roger Steffens’ The Family Acid: California (Ozma), gave me deeper insight into the strange California crucible that shaped me, as an early Gen X dude, at one remove.

Watching

I have been spending a lot time along the southern Mendocino coast of late, as much as possible really, but a few weeks ago I broke the spell and headed south to the city to catch the premier of Dennis Villeneuve’s Dune. I had been invited to see it at a small private screening organized by some friends over at the Long Now Foundation, a gathering that took away the heebie-jeebies induced by the specter of a packed house of utter strangers. I had just reread the book in anticipation of the flick (my second reread since teenhood), and I was preparing to be amazed and inspired and to channel that energy into an elaborate Burning Shore review that would dive into Dune’s treatment of religion, the story’s ecological underpinnings, and the Bay Area demimonde that Herbert, who palled around with Alan Watts, absorbed and transmuted when he wrote the first novels in the series.

Maybe someday. I did not hate the film by any means, but I found it kinda dull. More specifically, I found myself appreciating it without much emotion or imaginative spark. Another disappointment, in other words. Frankly I wish I had stayed in Mendocino, where the massive swells that accompanied the recent atmospheric river sucked away all the sand from a nearby cove, like a famished and watery Shai-Halud.

Don’t get me wrong. I was impressed and pleased at Villeneuve’s fidelity to the novel, at least in the portions it included. But I missed the baroque complexities and vexed interiorities of the book, not to mention the funky wackadoodle of Lynch’s version, which I watched in a fan cut years ago to great if sometimes strained amusement. (The best Dune film, of course, is Jodorowsky’s, playing at a parallel universe near you.) As expected, Villeneuve’s film looked terrific, his muted palette and sober minimalism well-suited to Arrakis and its war machines. The Baron was gross, the ‘thopters and shields convincing, and the worms and their spice intoxicating enough. I was particularly impressed by the Arrivaliste attention Villeneuve brought to the multiple modes of communication—hand signs, prophecy, the Voice—presented in the novel.

But the sand, as it does, got into everything. I don’t know about you, but the Lady Jessica in my head is a far less fragile character—any Bene Gesserit worth her salt, let alone one capable of birthing the Kwisatz Haderach, would have evinced more control over the mind killer, or at least more deftly masked her struggles. The teen hearthrob omens that struck Paul also grew mighty tedious, and it didn’t help that Zendaya, playing Chani, got framed as a pop exotica refresh of that Afghani girl from National Geographic. And though Herbert’s novel is one of the most sophisticated science fictions to engage the anthropology of the sacred, exploring both prophetic Abrahamic faiths and more mystical spiritualities, the film basically dropped these balls, dodging the abyssal depths of Paul’s spacetime meltdowns and, for the most part, missing the opportunity to have fun with the Fremen’s “Islamic” desert militancy.

But none of these explain the emotional vacancy of the film, which for all its action was stately and monotonous. Some critics have complained that Villeneuve was too faithful to Herbert, which gave the film a lifeless, overly reverent quality utterly lacking, say, in the delirious Lynch. I can hear that. But there is another, more interesting way to read this flatness, this sense that all the characters are simply going through the motions, and it has to do with how we read Paul’s destiny, and the attitude towards that destiny that animates the original novel.

Once Paul reads the writing on the proverbial wall, and understands the messianic fate before him, he performs what PKD always saw as the essence of ethics: he balks. Navigating the parallel currents of spacetime that Villeneuve did not even attempt to illustrate, Paul tries to dodge the coming jihad and his own autocratic role in it. He doesn’t want to rule but to simply abide…

But Paul’s efforts fail, and the path towards God-emperor and universal violence becomes set in narrative concrete. This sense of defeat, of human will foundering before the intransigent karma of myth, characterizes the grim irony that characterizes Herbert’s attitude towards his central protagonist, as well as his critical understanding of the religious patterns in human culture.

Some reactionaries celebrate Dune as an übermensch novel of old-school mastery and command, but these people are idiots who cannot read. Here the Hero’s Journey is really an implacable death march, a Penal Colony inscription machine, a self-fulfilling—and in the case of the Bene Gesserit, self-seeding—doom. Liet Kyne’s father, an offworlder who first bonded with the Fremen, tells them at one point that “No more terrible disaster could befall your people than for them to fall into the hands of a Hero.” In one of the appendixes in the first edition, Herbert is even more clear: the planet Arrakis (like the planet Hollywood) is “afflicted with a Hero.” From this perspective, the wan and mirthless narrative of Villeneuve’s Dune is an affective index of Paul’s submission to the already scripted demand of his own ascendence—a submission that the film also performs in sticking (relatively) close to a novel that so many have already read and reread. At a time of reactionary resurgence and increasingly fuedal brutalisms, not to mention the pervasive sense that “the story of civilization” has us by the collective throat, such fatalism cannot help but strike us as sobering.

Listening

I have been grinding through life for the last few weeks. Nothing major—lots of good things going down, though some bummers are afoot—but I have felt unusually afflicted by a stream of hassles, disappointments, missteps, frustrations, inabilities, and time-sucking tasks at once complicated and trivial, a typical 21C run I guess, but made more stern and enervating by all those looming Zeitgeist thunderheads about, swollen with their intransigent karma, ready to release their rain of suck. Though my sitting practice has been bearing fruit of late, it sometimes seems that my delusions have not dissolved nearly as much as my capacity for denial, and that whatever insight comes simply make more room for the fine-grained grok of dukha.

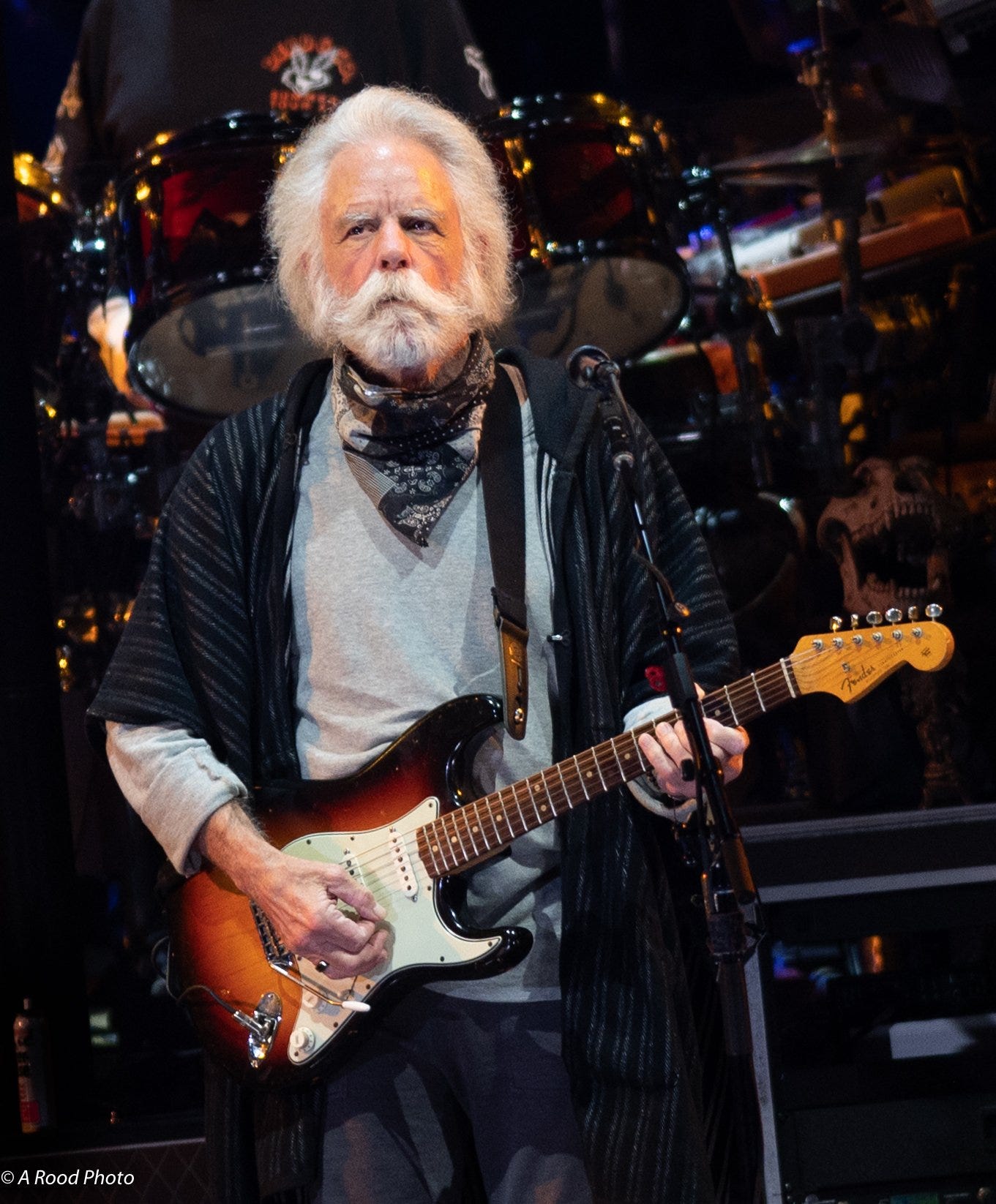

That’s why I am happy to say that I closed out the month with two Dead & Co. shows at the Hollywood Bowl. I’m lazy about tickets, but a pal with better connections and more foresight than I set me up. I missed most of the first set on Saturday night, as said pal—aka Jamie Wheal, author of the aptly named Recapture the Rapture—had woken up that morning at the bottom of a canyon in Utah and so was understandably a bit behind the ball, but had a fine old time nonetheless. We boogied near a small section of deaf folk, and watching one of the interpreters was as fun as watching the band. A middle-aged jester straight out of the Oregon Country Fair, he illustrated the music as well as the words, plucking out the syncopation and doodling along with the solos, a performance that provided a skeleton key to one of the Dead’s many mysteria: the whole song is saturated with signs.

That’s one of the reasons its so fun on drugs: the signs have more surfaces to bounce off of, more opportunities to trigger cascades, micro-eurekas, reverberant lines of flight. But you don’t even need the buzz (and I restricted my intake those nights to beer and cannabis). The Dead songbook—an illuminated storybook really, populated with wolves and warf rats, cowpoke Americana, and acid koans twinkling like diamonds—is such that, even if you know it by heart, it retains the capacity to surprise and signify. That’s partly what lends the whole thing a sacred or at least ritual character: the repeated reframings of resonant songs that most of the crowd know and often belt out in stadium sing-alongs is liturgically stable but enlivened, at least a lot of the time, by the holy ghost of the improvised and intensified Now.

The final night was one of the more revivifying shows I’ve seen in some time. While I was sad that an ailing Billy Kreutzman had to skip the show, I was not sad to enjoy the propulsion provided by pinchhitter Jay Lane. Though Bob Weir’s vocals seemed rusty at first, he found his groove, especially in the second set, where he managed to make “El Paso”—a song that often functioned in Grateful Dead shows as a sherbet-like palette cleanser between Big Tunes—into a Big Tune. And while Bobby’s attention wandered at times, and his bone-white Yosemite Sam ‘stache spoke the tickings of the clock, his eyes were still young, or at least faraway and strange.

It was also the best night I have seen by far from guitarist and terminal pretty boy John Mayer. I have not loved him in the past, though I always tried to give the guy a break. It’s not easy to stand in Jerry’s shoes, working an idiosyncratic musical current that paradoxically must be improvised upon to retain its essence. On Halloween, and especially on “Althea” and “Eyes of the World,” Mayer showed he was not a clown in Garcia’s burying ground. His slowhandy licks, modal explorations, and nearly subsonic butterfly runs unspooled and reinscribed Jerry’s stylistic DNA while leaving room for less scripted interplay with keyboardist Jeff Chimenti and occasional forays into more singular Mayeresque zones. Rather than telegraph any lack of invention or fire, his nerdy, bedroom-musician reserve—communicated by onstage headphones and modest, non-hippie style—somehow underscored his ability to thread the third eye of a very peculiar needle.

But I can’t write as a critic here, or don’t want to really. I would rather just embrace the holy foolishness of Deadheadom, of loving much of this music very much, and feeling grateful for all the thrills and spills and sublimities it has revealed over the decades, as well as its capacity for release and renovation. If this sounds a bit “religious,” I’m OK with that—nebulous spirituality is easy to find in the freak zone, but its in religious needs and patterns that the rubber hits the golden road. Not dogma or militancy now, but deep story, and a collective structure to mint revelations out of neural fritz. That’s religio, the ties that bind: the unbroken circle, the unbroken chain. And that night it totally worked: bone-dancing and singing along, I felt healed and whole, and the following days were infused with a sense of good-will and ease sustained enough, at least in this personality, to count as mild euphoria.

Sunday began on an appropriately churchy note, with the traditional Old Testament tale of “Samson and Delilah” followed by what I’ve always heard as the hippie New Testament promise of “Uncle John’s Band” (John the Baptist, by the riverside, seeing the light). There is a subset of Dead songs that inspire kumbaya, and this one brought the children home. Other old-timey story tunes that night—”Dire Wolf” and “Brown-Eyed Women,” the first Dead tune I learned on guitar—made common cause with common suffering, a crucial binder of religio. And now I too can attest that the old man is indeed getting on, part of the reason for my SoCal sojourn in the first place.

Earlier that day I had thought of two Big Tunes I wanted to hear, and I got ‘em both, “Terrapin Station” and “Eyes of the World,” the latter being the musical highlight of the show. I want to write about “Eyes” some other time, but the early verses of the “Terrapin” suite is important here because of one absolutely crucial existential twist I need to add to the religious reading of the Dead I am offering. In the Christian context, religion offers a rock, a faith and a rule and a more-or-less defined community of believers. But the Dead’s sacred is without foundation, without messiah or hero or rules for the human zoo. Reason is tattered, delusion an ever-present possibility, even a likelihood. The paths through these ashes are beyond belief, offering only the possibility of that singular gnostic spark that Harold Bloom identified as the essence of American religion, a transient nightfall (un)knowing that, as Wheal describes in his book Recapture the Rapture, also resonates with the ecstatic deeps of psychedelia.

When “Terrapin” announced itself, Jamie settled back in his seat. “It’s storytime,” he said. But this story too is an open-ended one, and feels improvised despite its folkloric familiarity. At the heart of the tale is a Sailor and a Soldier, who are challenged by a Lady who throws her fan into a lion’s den:

Which of you to gain me, tell

will risk uncertain pains of Hell?

I will not forgive you

if you will not take the chance

With the Lady’s coupling of forgiveness and infernal risk, we are already outside the Christian story, just as, in “Eyes,” a redeemer comes and then fades away, leaving a vehicle, or yana, filled with the same old human clay. But the deeper sacred irony here is that the meaning of the Lady’s dare is itself up for grabs. After the Sailor leaps into the breach, we—the hearers of the tune—”decide if he was wise.” This is not the singer’s purview:

The storyteller makes no choice

soon you will not hear his voice

his job is to shed light

and not to master

I took these words to heart long ago, and they still guide my hand. Earlier that evening I had spoken with Jamie about my career, and his curiosity about my ambivalence and what he called my apparent “nihilism.” I pushed back against that word, but I know what he means. Out in the world, Wheal is doing his damndest to lead, to cajole the sinking ship to right itself, to influence and train the other, whereas I feel increasingly resigned, at least beyond a certain charmed circle of insiders. Age and alienation are playing a role in all that, but this sense of refusal has always been part of the package. Whatever my gifts, I have never wanted to be a bigwig or a guru or a thought leader or an organizer. I have never wanted to save the world. And I can trace part of that ethic here, to a powerful sense of vocation that sheds light but refuses to master—that is, to rely on the discourse of the master, of “the one who knows,” or the one who masters meanings by resolving them or presenting them sewn up with a bow.

I am the first to admit that such ambivalence might be profoundly flawed, more a failure than a strength, or at least an insufficiency, especially with today’s turn of the wheel. But I’m a grace guy, not a works guy, and for grace to be unearned, it must be undecided. Such psychedelic grace animates one of the great lines in “Scarlet Begonias,” which garlanded Sunday’s second set: “Once in a while, you get shown the light / In the strangest of places if you look at it right.” In other words, you don’t make it happen, but you need to train yourself to share the happening. In “Terrapin,” the word for that light is inspiration:

Inspiration, move me brightly

light the song with sense and color

Hold away despair

more than this I will not ask

Faced with mysteries dark and vast

statements just seem vain at last

In this prayer, perhaps the most petitionary in the Dead catalog, we can glimpse the vision that motivates the refusal to master—a refusal that is more than some postmodern fetish for indeterminancy or a quavering inability to make up our minds or get it together. The refusal to master, ideally, is a kind of humility that models a response rather than demanding a stance. We ask to be moved, not to understand or define, an invitation to the Other and an affirmation of how little we know and how little we ultimately need. Relief from despair would be nice, of course, and I am grateful for the dollop I received that night. But more important is the animation of that Song of Myself that we no-selves get to sing for a spell, sometimes with others, and sometimes all on our own.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

I'm yet to see Dune and oddly don't feel particularly compelled to. I've always meant to read the novel before watching the Lynch film and have so far done neither. While that is clearly an issue, I've also fallen out of love with Villeneuve's work a bit. I re-watched both Arrival and Blade Runner 2049 in recent months and, while they are spectacular in some respects, they are also a little clunky. For all they look incredible, they are both surprisingly quite weighed down with clunky exposition that prevents them from being masterpieces. On first viewing, I thought BR2049 enriched the original Blade Runner, but second time around I was left feeling a little flat. All of the rich religious subtext I'd gotten excited about in the cinema just didn't seem all that interesting. Arrival bowled me over emotionally the first time I saw it, but much of its cleverness was down to the way the narrative unfolds. Its remarkable that Villeneuve made a film about language so visually arresting and Amy Adams is phenomenal in it, but there's just something lacking. Its hard to put a finger on what exactly. Something about your Dune review kind of nailed it for me even though I've not seen that specific film. It makes me wonder whether Prisoners was his best film all along. All of this has made me really want to finally grab a copy of the novel anyway, so that's something!

Hey that first Dharmanaut guided meditation is a gem, thanks for making that available.