I Was a Teenage Jesus Freak

Plus News and Notes

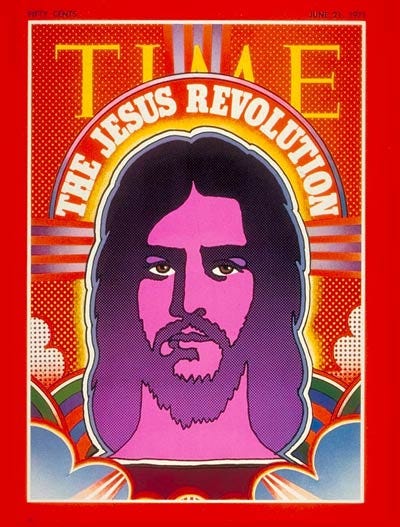

One thing that the Christmas season really hits home is that, even if you are living on the atheist edge of what many experience as a secular, postmodern, polarized culture, there is no escaping Jesus. His continued imaginal presence can feel oppressive to non-believers, but I think folks are making a mistake when they try to flee or erase or overwrite the figure. To live and think and imagine in our time and place means to have some sort of JC in your head. The question should not be, why is JC still in my head? But rather, which JC is in my head? For of course, they are legion. There is gospel r&b Jesus, magic New Age Jesus, little baby Jesus, Santo Daime Jesus, hunky Jesus, Hallmark Jesus, “arc of history” Jesus, rave Jesus. It’s kind of a choose your own adventure situation, one that even believers are performing, though they largely refuse to admit it. It’s not necessarily about worshipping the guy, but about accepting an avatar on your team who might counterbalance the less savory Saviors promulgated these days — AI-ripped Jesus, vengeful Jesus, Aryan Jesus.

My favorite Jesus is the freaky Jesus, the long-haired outlaw cosmic prophet who rode the cultural imaginary in the early 1970s. There was a broaderer cultural turn to Jesus at the time — think Jesus Christ Superstar and the Doobie Brothers. But he also rose high in the hearts of the Jesus People, aka the Jesus Freaks, who found their “one way” to the Savior from within the druggy occult youth scene of the late 60s. Later in this post you will find a lecture I recently gave on the “psychedelic Jesus of the counterculture” at Harvard Divinity School’s Center for the Study of World Religions, where I had the honor to be a scholar in residence this fall. But before we get to that, I thought I would reflect on some of the personal lore that lies behind my long-standing fascination with this figure and the scruffy street Christians who followed him: my own brief teenage sojourn, during the spring of 1983, as a born-again Christian, SoCal-style.

Where to begin? A number of years ago I was gathered around a table with friends, including two other Californian males roughly my age (I am now pushing 60). A question came up: When was the weirdest time of your life? All three of us immediately answered: “when I was 14 years old”. Why the coincidence? My personal bet is that the permissive subcultural milieu of California in its post-hippie heyday provided just the right fuel to supercharge the liminal headspace of mid-puberty. Reflecting on my own experience, 14 seemed to mark a time when the mind, anxiously and greedily opening up to adult desires and concerns, was still high on the pixie dust residues of the preteen myth-mind. It made for a time of sullen magic.

Drugs didn’t help (but they didn’t hurt either). I started eating acid on Halloween in 1980, when I was 13, tripping out to “Careful with that Axe, Eugene” in the colorfully festooned loft that Bry-Fry had built in his family’s garage. By sophomore year, me and my gang of half-throwback freaks were cooking along with shrooms, windowpane, and the excellent cannabis products our position on the globe — coastal San Diego County, aka “North County” — afforded us in the early 1980s. My friends and I absorbed counterculture lore, mostly through books and records and VHS tapes of Performance and 200 Motels. But we also had direct encounters with wandering hippie monks and Zen guys and a former est leader who taught “Epistemics” at our high school, Torrey Pines High, which was also Tony Hawk’s alma mater. We caught rides to UCSD to see Ram Dass and to the Siddha Yoga Center down in Kensington, where we would toke up in the car before chanting “Hare Krishna” for hours.

At 14 I was reading stuff like Castaneda, Lovecraft, Hunter S. Thompson, Dune, and Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. I started meditating as well, boosting the gain with resin hits, and discovering humanity’s infinite capacity to entrance itself. A particularly excruciating trance accelerant was my phantasmagoric and unrequited crush on Barbara Zinke, a girl I took for a budding white witch. Into this heady, horny mix came various occult attractions — I Ching, Tarot, astral travel, and Crowleyan magick, at least fantasized via John Symonds’ scandalous biography. One summer a few of us, including the crush, got our hands on a mimeographed spiral-bound Book of Shadows, and were soon drawing down the moon.

I had a number of anomalous experiences in those years, including creepy lucid dreams, an old hag on my bed, a doppelganger in my mirror, a cosmic lovebomb from Ram Dass, and a galactic download from a mystical satellite signal that popped into my head the same year, I would later learn, that Philip K. Dick died. These visionary intrusions were of a piece with the pockets of the mystical marvelverse my friends and I stumbled into as we wandered tripping through Del Mar, a coastal suburbia that, blessedly, was dotted with arroyos, funky culverts, beach access, 7-11s, and amusing surfer keggers.

In the fall of 1982, having turned 15 and in junior year, things twisted towards the dark, at least in my head. I took a course in Comparative Literature from the wonderful Dee Frank, who let me choose most of the books I read. I started out staring at the void with Sartre before moving on to Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (in the classic 1958 Leclerq translation), which helped demonize my abiding horniness. Then I consumed two books I still really love, Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita and Mann’s Doctor Faustus, both of which happen to feature Satan. I grew more grim and isolated, certainly from my family, and sometimes had lucid nightmares and dark hypnagogic encounters. Though I didn’t get into any real-world trouble, I was sinking into something more twisted than depression. I wrote fetid Dungeons & Dragons poetry, listened to tons of Van der Graaf Generator, and became obsessed with the idea of “sophisticated evil.” (Don’t ask.) I crowned the semester with a Christmastime reading of Kazantzakis’ The Last Temptation of Christ, which got me obsessed with Judas, a rebel figure I had first fallen for years earlier during repeated listenings of my Mom’s scratchy copy of Jesus Christ Superstar. My mind was even clearer now, I thought, and I became convinced that Judas’ betrayal was the key to Christ’s cosmic passion.

My family was not Christian. Jesus was on my mind because of another consequential class I took that fall: typing. It was consequential not because I learned something that’s still actually useful, which is true, but because of the two dudes I sat behind as we ratta-tat-tapped our way through the drills. One guy was a chunky blond surfer and the other a semi-feral metalhead with a mullet. They weren’t particularly smart, but they were friendly and talkative. They also happened to be newly born-again Christians, and hot to spread the news. I grilled them about their faith, a well-established habit of mine since junior high, and they eventually invited me to a Bible study that took place Friday nights in a house in the Del Mar highlands near the interstate.

I don’t recall the order of events now, but somehow between the invitation, my peculiar headspace, and my reading and writing, something shifted. I didn’t have a come-to-Jesus moment, but something more like a melty mutation over a number of weeks. I started to attend the Bible study gatherings, which took place in the living room of a small tract home with beige wall-to-wall carpeting, which was usually packed with a dozen or so teenage souls. Our exegete was a young man with shaggy hair and an impressive command of scripture, which he strung together in the loosely Pentecostal and fundamentalist style favored by many otherwise informal SoCal evangelicals of the era. Michael offered compelling readings whose content I recall much less than his passionate, commanding, but laid-back style. If you have ever listened to David Koresh preach in one of his less apocalyptic moods, and you’d have a decent sense of Michael’s charismatic blend of scriptural citation and dude-sprache.

My favorite relic of those months is a version of the King James Bible I picked up at a Christian bookstore at a strip mall near the coast. The store, which I visited a number of times and was more important to me than any particular church, was one of the many nondenominational Christian shops that popped up in the 1980s, paralleling the New Age stores of the era with their spiritual lifestyle blend of books, cassette tapes, bumper stickers, statues, jewelry, and inspirational wall art.

The Bible in question, which I still own, was a more old-school affair: a faux-leather-bound copy of the Dake’s Annotated Reference Bible. On its thin scritta pages, the 17th-century King James prose was copiously, almost talmudically broken down with over 35,000 notes and commentaries crammed into side columns and myriad appendixes. Its author was one Finis J. Dake, a Pentecostal evangelist from Missouri who, after violating the Mann Act in 1937, became the first Pentecostal to publish a scriptural reference work on anywhere near this scale. Imagine a listaholic fusion of Jack Chick and Charles Kinbote, the deranged literary critic who animates Nabokov’s Pale Fire, and you would not be far off. Here, for example, are some facts about angels tucked into Dake’s notes on Psalms:

They need no rest (Rev. 4:8); can eat food (Gen. 18:8; 19:3; Ps. 78:25); appear visible and invisible (Num. 22:22-35; Jn. 20:12; Heb. 13:2); operate in the material realms (Gen. 18-19; 22:11; 2 Sam. 24; 2 Ki. 19:35; Acts 1; 12); travel at inconceivable speed (Ez. 1; Rev. 8:13; 9:1); ascend and descend (Gen. 28:12; Jn. 1:51); speak languages (1 Cor. 13:1); and can do anything man can do, including sin.

Dake’s interpretations today are largely considered “personal,” aka wacky, with fanciful Aramaic etymologies and Clarence Larkin-style dispensationalist illustrations. At the time I thought I had fallen in love with the Word, but I think what I really fell for was obsessive hermeneutics — the kind of conspiratorial intertextual “readings” that would later make a Pynchon and Illuminatus! fan out of me. The doctrine of Biblical inerrancy I imbibed did strain credulity, but its literalism also made for some wonderfully phantasmic bedfellows — angels that eat food and travel at inconceivable speeds, just like UFOs.

A number of years later, I took an English seminar at Yale called The Bible as Literature, which was taught by Leslie Brisman, a wonderful teacher and a student of both Harold Bloom and an orthodox yeshiva. It was a profoundly influential and engaging experience. One day in class we were discussing the King of Tyre, who appears in Ezekiel 28, and I said, “That’s Satan.” Brisman gave me a quizzical, intimate look, as if we had discovered we might share the same great-aunt. “How did you know that?” Thank you, Finis Dake.

As a high school born-again, I did not exactly conform to the mold. I didn’t like the groupthink vibe at the nondenominational church the Bible study kids attended, nor did I get baptized, which I was tempted to do, my parents having kept me heathen as a babe. Though I stopped taking drugs, I didn’t cut my hair and still hung out with my stoner pals, to whom I learned not to witness too heavily. In some ways I approached my new faith as a head. I had some trippy visions, which I took very seriously, though I feared one of them may have been the satanic simulacra that Paul warns about in 2 Corinthians. I slipped into tongues a few times, and had something devilish shaken out of me one Friday evening after lapsing into what I would now identify as a spontaneous kriya. In other words, I remained a seeker, up for peak experiences, kinda solo, and fascinated with resonating signs and wonders.

I did worry about demons, too, having spent so much imaginal time with them the previous fall. But as the months rolled by and my brain remained sharp, I grew tired of the widespread Christian fetish in those years for demonizing popular culture. Though I bought records by Phil Keaggy and a few other Christian acts, I kept listening to secular rock and prog because it was just way better. I remember chatting about Peter Gabriel with one of my brethren, and he promptly condemned the artist’s “Shock the Monkey” video for its demonic African paganism. I understood the concern, but he still sounded like an idiot.

Cracks like this continued to grow, and the inevitable contradictions inherent in the literalist approach — like trying to square the two creation stories crammed into Genesis — left me more bemused than believing. I was trying to stay in the groove, to not “backslide,” but the writing was on the wall. That June I turned 16, which meant a driver’s license and, finally, a girlfriend. By the end of the summer, I was eating blotter and dancing to the Dead.

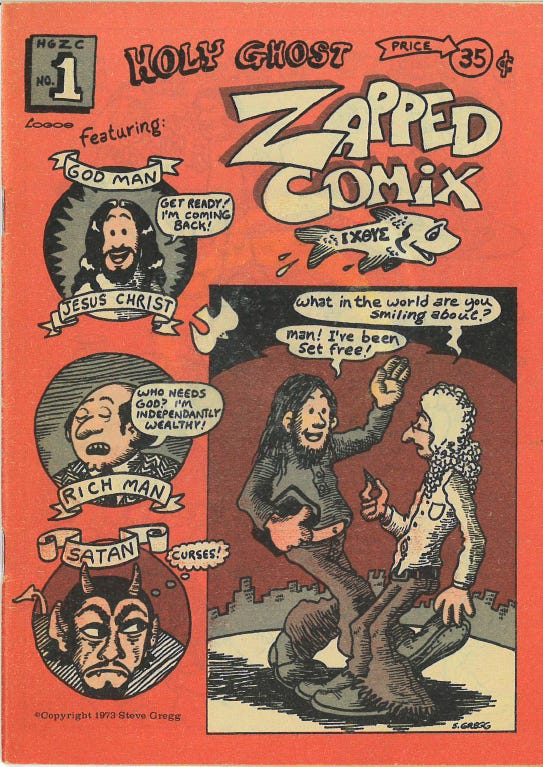

Over the decades, as my own path splintered and mended itself into a California crazy quilt I can’t even map anymore, I never quite lost that JC-shaped hole in my heart. These days I continue to read scripture, apocryphal and otherwise, and find sustenance and imaginal challenge in esoteric, literary, and radical sides of the faith, from the atheist Christianity of Žižek to the poetry of George Herbert and Thomas Vaughan to the Orthodox doctrines of theosis. I also study Christian history when I can, fascinated if regularly repelled by cranky old cenobites and creepy new nationalists. And I continue to research the Jesus People, those scruffy street Christians who first emerged among druggy hippies in California before exploding into national prominence.

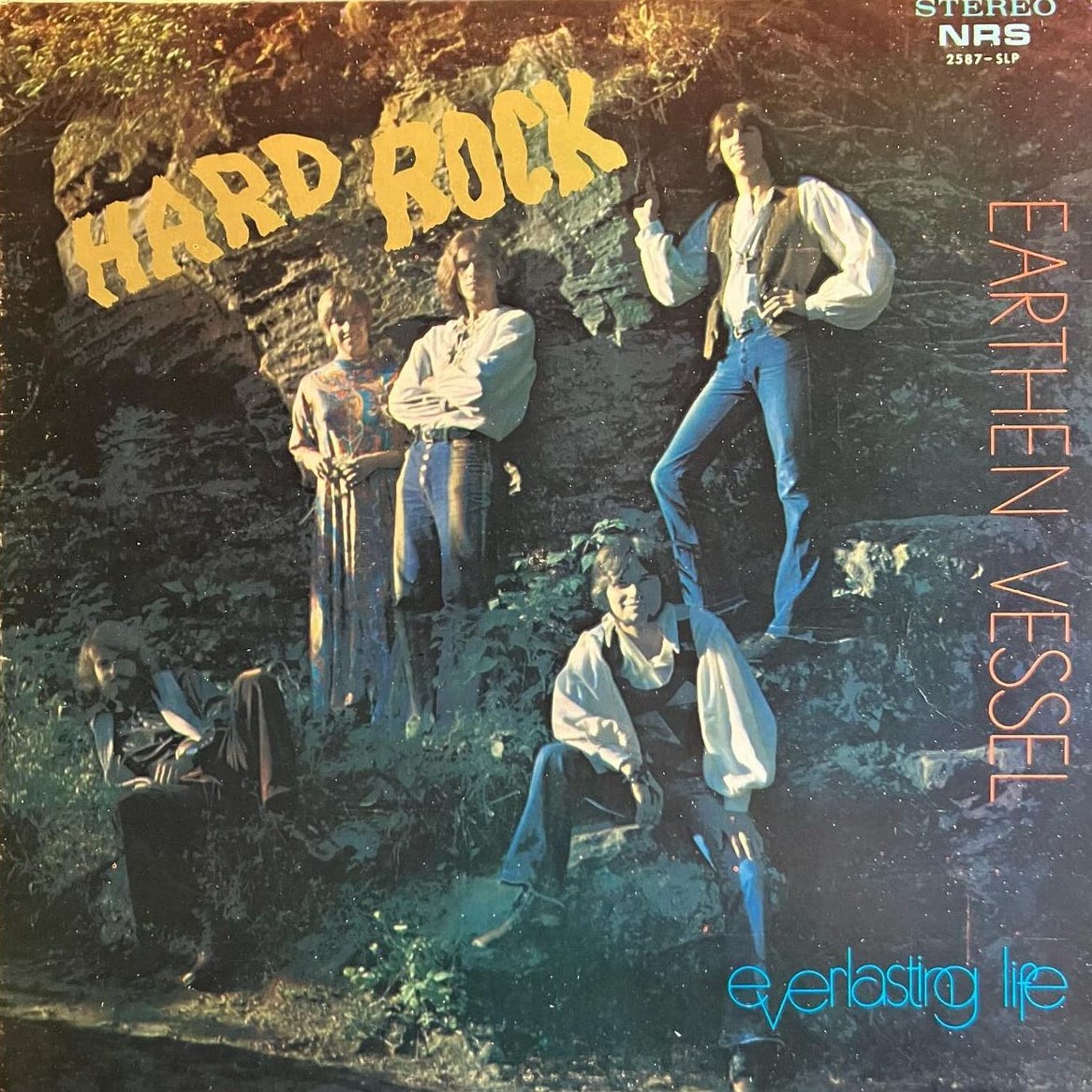

Part of my attraction to the Jesus People is personal, as if immersing myself in these moldy subcultural vibes allows me to catch a lingering whiff of the sweet enigma of my own born-again experience, which also took place after a teenage plunge into LSD and the occult. It’s not the theology that draws me, but the earnest charm, and then only at one remove. As their “underground” newspapers show, Jesus People discourse is mostly strident, predictable, and naive. But when they picked up electric guitars, things could get beautiful and heavy. There is an impressive amount of amateur Christian rock and folk from the Jesus People days, mostly appearing on private-press LPs, most of which are as medicore as they are rare. But there is gold in them thar hills. Years ago I started collecting the stuff, both reissues and originals. At first I favored gnarly psych monsters by groups like Fraction, Agape, Azitis, and the Exkursions. But I developed a taste for some of the schmaltz as well, crunchy folk-rock praise songs and bittersweet ballads whose artless sincerity can, in this outsider’s heart anyway, serve up the most singular of feels.

Jesus People are also fun to think about. As a student of wayward postwar religiosity, I am fascinated by the anomalous role that these hirsute converts play in counterculture history and memory. Should they be seen as just another variation of the novel spiritualities that bloomed following the psychedelic youthquake of the late 60s? Or, as the Jesus People themselves liked to think, did they represent a total backlash against stuff like gurus, Zen, paganism, and the human potential movement? Things are just as unclear on the Christian side. Were the Jesus People just another American revival movement, or did their hippie origins introduce something new and radical? Historians of American Christianity still debate the significance of the movement, some seeing it as a flash in the pan, and others arguing that we don’t get blue jeans and acoustic guitars at suburban mega-churches without it. You certainly don’t get Bob Dylan’s great gospel period without it. And I am pretty sure you don’t get born-again surfer Bible study groups in Del Mar without it.

As mentioned above, this October I found myself at Harvard’s Center for the Study of World Religions as a visiting scholar. The CSWR, which runs a lot of excellent public programs and has a terrific mailing list, has been exploring psychedelic humanities of late. I decided to focus my research time there on a very particular question: how do we understand the role that psychedelics played in the Jesus People movement and particularly in people’s conversions, which sometimes involved LSD? How was that influence narrated, and repressed, and paradoxically acknowledged? I took full advantage of Harvard’s libraries, turning up a number of rare books and scholarly studies, including David Di Sabatino’s scarce and excellent annotated bibliography The Jesus People Movement, which also includes an extensive guide to the music of the era. The following lecture is the result of that research.

Upcoming Events

• The Phurst Church of Phun

For this month’s Chalice, which will take place at the Berkeley Alembic on Wednesday, Jan 7, at 7pm, we will be welcoming Johnny Dwork, a multimedia artist, Oregon psilocybin guide, and renowned producer of psychedelic music and art festivals. In 1984, the legendary Merry Prankster Wavy Gravy ordained Johnny as The Rabbi of the Phurst Church of Phun, an underground society of comics and clowns that first emerged from the protest movements of the 1960s. Through a wide variety of theatrical and comedic modalities, Johnny has since helped thousands of people embrace good-hearted humor as a vehicle for health, healing, and more playful approaches to psychedelic experience. Johnny and the full Chalice crew will discuss sacred foolery, mystical mirth, and the role of clowning in activism, as seen recently in his hometown of Portland, Oregon. In the second half of the evening, initiations into the Phurst Church of Phun will be on offer. Click here to attend in person; alternative for online only (which will only feature the first-half discussion).

• The Occult Internet

Things are getting weird online. Beyond fake news, AI slop, and social media madness, our digital ecosystem seems to be eroding reality itself: tech bros believe we live in a simulation, people debate false memories known as “Mandela effects,” young people are “reality shifting” between different dimensions. To help break it down, join me at the Alembic to hear Internet scholar Shira Chess discuss her new book, The Unseen Internet: Conjuring the Occult in Digital Discourse. Shira tracks a lot of the weirdness to the 1990s, when many of the people shaping early Internet culture were also hacking reality, practicing Technopaganism, and engaging in other forms of alternative spiritualities that intersected with emerging technologies. For the book, Chess interviewed a hodgepodge of characters who were influential at the dawn of the commercial internet, including me. Her conclusion: it’s kinda our fault. Joining Chess for the evening will be a panel of OG techheads including myself, Paco Nathan (Machine Learning, AI expert and editor of the great FringeWare Review), Mark Pesce (Co-inventor of VRML, futurist, and host of the podcast The Next One Billion Seconds), and R.U. Sirius (Editor of Mondo 2000, Reality Hackers, and High Frontiers). In-person link; online-only link.

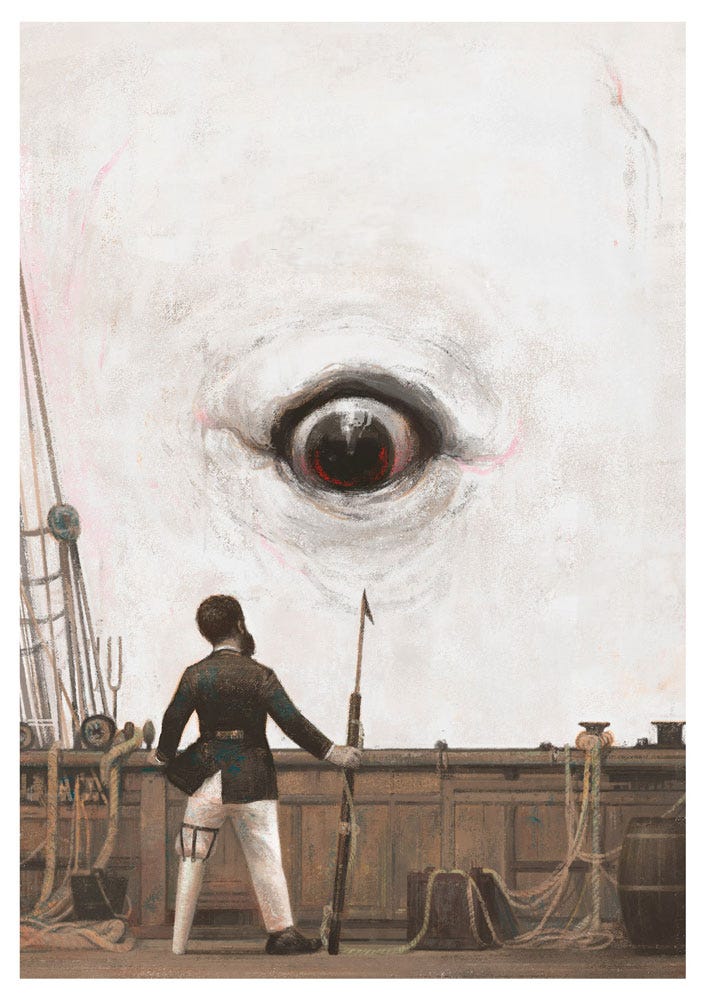

• The White Whale

Since embarking on Moby-Dick for the third time, I have found wakes of the white whale everywhere: mentions in the manosphere, by the integral wizard Layman Pascal, even on Ross Douthat. If you have yet to make the voyage, or want a return to the maelstrom, please consider joining me and Weird Studies co-founder J.F. Martel for our six-week class devoted to Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick. Prophetic, mystical, and unhinged, the novel is a book of riddles and mysteries, a secular scripture that wrestles with myth, modernity, the dangerous project of America, and the gnostic (and weird) dimensions of reality. J.F. and I love this book, and as we bring it into conversation with religion, philosophy, esotericism, and natural history, we have no doubt that the Whale will speak to us all. Class meets twice a week — a lecture slot where J.F. and I riff and roll, and an office hours session for discussion. For more info, follow this link, which gives Burning Shore readers a 10% discount.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. More than anything, I want to resonate with readers. If you would like to show support, the best thing is to subscribe and to forward my posts to friends or colleagues. You are also welcome to consider a paid subscription, and you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

Fascinating stuff, thanks. I’m glad I ran across your post. Weirdness attracts weirdness as I’m sure you know. I was also a teenage Jesus freak (well, a 20 year old Jesus freak) and I think you might be interested in my tale, especially as you mention a respect for Dylan’s gospel era. It’s up your alley—astral travels, rock and roll, sex and drugs, hidden messages. Take a look at my articles if you like, and be sure to start at the first chapter, where I tell my Jesus story. All the best,

Steven

hi Erik. I enjoyed watching your presentation again. (Met you at the Harvard thing.) Blessings, Ray Connolly (ex-cult guy.)