Ishi's Cave

The Burning Shore, no. 4

Last Friday, I once again headed down to Golden Gate Park. I needed to clear my spinning head and ease a particularly freighted heart. While I had a few fine critter encounters, including an eye-to-eye with a fledgling hawk perched low on a nearby eucalyptus, the effort failed. There were just too many fucking people. The weather was tasty, the panic’s dimmed, and so “they” were everywhere, exploring all the nooks and crannies, tearing up the trails on mountain bikes, yapping away about zoom meetings and masks, doing that modern human weekend thing on a weekday that, a few months or even weeks ago, would have drawn a far smaller crowd.

I wanted birdsong, and so I headed toward the woodlands in the northeast corner of the park, where some of the last remaining old-growth oaks in the city continue their now ancient shelter-in-place. With their help, I started clawing my way towards some sort of half-assed philosophic calm. Then I heard a loud hand-clap behind me: a jogger alerting me to his presence. It seemed an obnoxious gesture, but whatevs: I followed the same protocol I have maintained for weeks, pulled on my mask and crammed up along the edge of the path, turning my face away. But this was not good enough for Mr. Bro. “Hey aren’t you going to step off?” he demanded in an imperious tone. I was in too foul a mood to respond—I can be a mouthy asshole, so that wouldn’t go well—and so, rather that hustling into the bushes, I shuffled forward until a cross-path let me give him the full local allotment of six feet of separation. He jogged by with a snide “Thanks” and an all-too-familiar odor of douchebag entitlement, that sweet stank of San Francisco success.

The next morning I left the house at 6 am and walked uphill rather than down. I climbed the Farnsworth Steps—named for the Mormon inventor who concocted the first all-electronic television system on Green Street in 1927—and got up into the lovely volunteer-maintained trails that thread through the eucalyptus forests on Mount Sutro. (Inwardly, I call the place Mount Parnassus, the high hill’s original and superior name.) The robins and goldfinches were out in force, and so were the spontaneous shrines.

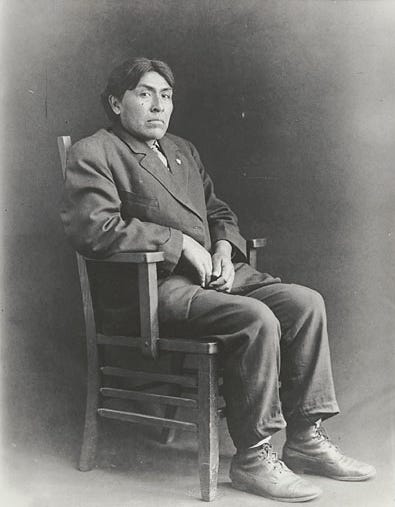

Way to go, humans! After a satisfying stroll, peppered with intentionally friendly greetings to make up for the social funk of the day before, I headed down to Cole Valley for snacks. I passed by the Grattan elementary school that my Nana attended almost a century ago. In the corner of the scraggly streetside garden, there was a display case announcing “The Ishi Watershed.” WTF? Alongside an explanation of a watershed, there were a number of photographs and short texts about Ishi, the Yahi Indian who, along with Hunter S. Thompson, was one of the most famous residents of Parnassus Heights, the hilly neighborhood around the UCSF Medical Center where I live. I feel sort of vulnerable admitting this, but I got all weepy-eyed.

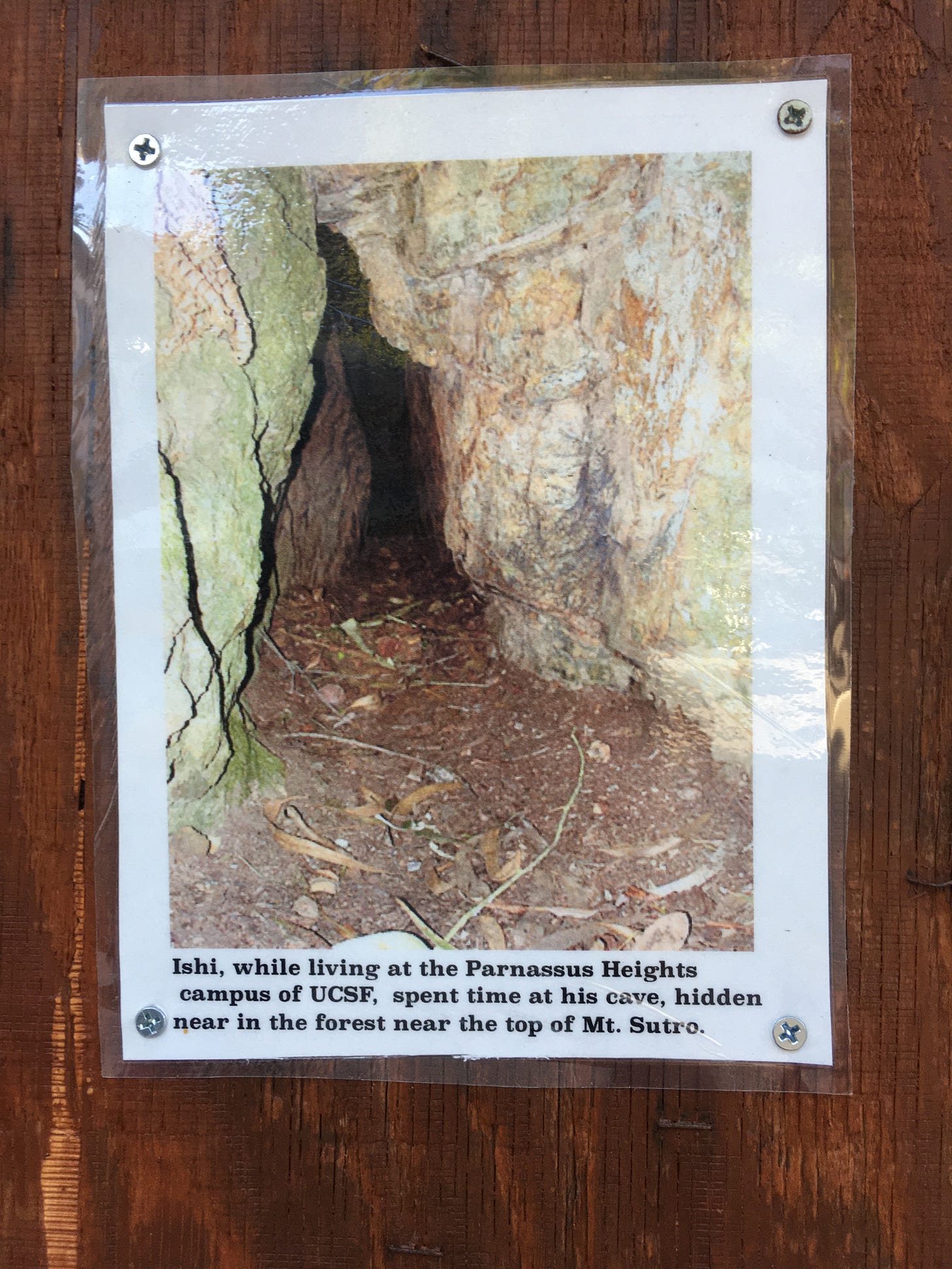

Part of the reason is that I had been thinking of writing about Ishi here, but felt conflicted about it. If you are a distant scion of settler-colonialists, a non-specialist who has never even attended a bear dance or a NAC ceremony, you probably want to step carefully into the matter of Indians in California. This land’s indigenous cultures were spectacularly varied, and their treatment at the hand of the Anglo incomers was spectacularly brutal, even by the bleak overall measures of North American colonization. I also wanted to talk about Ishi’s cave, a cleft in a chert outcrop near the top of Mount Sutro that I sometimes like to visit. I wasn’t sure about spreading word about the site, which everyone I’ve talked to who might know anything agrees was a place Ishi liked to hang out. But there it was: a photograph of Ishi’s cave on the Grattan board. I took it as a thumbs-up from the synchro lords.

In 1911, Ishi was captured, emaciated and probably starving, in a slaughterhouse in Oroville. He was the only survivor of a small family band of Mill Creek Indians (or Yahi) who had, remarkably, hid out for four decades in the thorny foothills of Mt. Lassen, following their diminished lifeways after a series of atrocious massacres in the 1860s and 70s. A few years after the dwindling band encountered a survey party, who stole a lot of their remaining stuff, Ishi’s companions died. He was alone in his home, and so left it.

The usual story implies that he “gave up” when he headed into the white man’s world, though some believe he was headed to Maidu territory to seek out distant relatives when he was captured. In any case, he soon found himself in the care of Arthur Kroeber and T. T. Waterman, two anthropologists from the University of California who studied the state’s Indians. They were stoked: here was a genuinely “uncivilized and uncontaminated man,” an extraordinary scoop for salvage anthropologists like them, who labored to catalogue indigenous languages and cultures on the edge of what they saw—incorrectly, it is crucial to add—as inevitable oblivion.

So that’s how Ishi wound up on the side of Mount Sutro, where UC’s anthropology museum sat alongside the budding progenitors of today’s humming medical complex. Ishi lived in the very museum where some of artifacts of his own people were on display. Partly to justify the support that kept him there, Ishi was made the janitor, while he spent the weekends demonstrating his skills at fire-starting, archery, and arrow-making to large crowds. He didn’t just stick to the native habitus, either. He sometimes knapped modern glass for arrowheads, which he attached to shafts with novelties like glue and cotton string. He had an interesting relationship with the new technology around him: he was more impressed by matches and mechanical window shades than airplanes, and found the sheer numbers of city-dwellers more shocking than their noisy vehicles. He enthusiastically recorded dozens of hours of stories and songs on wax cylinders, and had little shyness before the many cameras that turned his way, as in this “authentic” scene staged by Kroeger during their one return trip to the Lassen foothills.

On one level, Ishi’s peculiar situation recalls the display case that the exotically garbed performance artists Guiremo Gomez Pena and Coco Fusco inhabited a century later in their piquant performance piece The Couple in a Cage: Two Amerindians Visit the West. But Ishi, it seems, managed to carve out a dignified life at the museum, forming close friendships with the Watermans and a nearby doctor, with whom he liked to hunt, and exploring the city with his wily pal Juan Dolores, a Tohono O'odham Indian who served as another of Kroeber’s informants. Though Ishi was creeped out by all the bones at the museum, he chose to stay in the museum when offered the chance to move to a reservation. Ironically, if he had been in an exhibition case, and not constantly mingling with whites who wanted to meet “the last wild Indian,” he might not have caught the tuberculosis that killed him in 1916.

By all accounts, even revisionist ones, Ishi was a mensch: patient, friendly, curious, upright. He weathered the sort of radical and traumatic change that would destroy most of us, and he did so with an unflappable calm that, as his joking and frequent delight suggested, had nothing to do with stony-faced stereotypes of native imperturbability. There was a charm to the man that radiates throughout his story, throughout time even, which is partly why his print-outs of his image are now stapled to that signboard at Grattan.

But for all the clarity of his spirit, Ishi remains profoundly veiled, especially in the dimension of language. The linguistic diversity in pre-contact California, where many Indians lived in small localized groups, was extraordinary, perhaps the richest on the planet. The Mill Creek Indians spoke the southernmost dialect of Yana. When Ishi’s companions died, he found himself on the edge of that stark void that is the extinction of a language, and of the particular world that language engenders, and that void seeps through his story. He died before he and the ace linguist Edward Sapir could complete a workable portrait of his tongue—indeed, the exhausting work they performed together that last summer probably worsened his condition. He never spoke much English, and he never revealed any of his Indian names to the whites—“Ishi,” Kroeber’s bestowal, is the Yana word “man.” Nor did Ishi ever speak about the massacres the Mill Creeks suffered, nor about the reasons he finally left the territory. Today, despite ongoing linguistic work, his recordings remain largely untranslated, his language a scholarly sketch. This is why Gerald Vizenor, the Native American author and postmodern scholar, calls him “Ishi Obscura.”

In its strangeness, its economy, and its bittersweet load of human interest, Ishi’s story is hard to beat. As such, it has been major California lore since Theodora Kroeber, Arthur’s wife (and, with Arthur as sire, Ursula K. Le Guin’s mom), published Ishi in Two Worlds in 1961. Despite some inevitable flaws of tone and fact, Kroeber’s book has aged pretty well. She does not whitewash the particular horrors of California’s settler-colonialist violence, nor does she reduce Ishi’s story to “tragic pathos”—a sentiment that, already by Ishi’s day, had come to define a liberal, bleeding-heart version of manifest destiny that held up the nobility of American Indians at the very moment of their presumed disappearance.

My discomfort around this sentimental minefield is one of the reasons I wobbled over fessing to my enchantment with Ishi here, a love that is rooted in a naive childhood sense of place and story that only later grew into a vexed and tangled awareness of the historical contradictions involved. (Some of these contradictions are reflected in the worthwhile 1993 documentary Ishi: the Last Yahi, available on Youtube.) As the Grattan board reminds us, Ishi plays well for settler-colonialist kids, just as he apparently enjoyed playing with such kids when they came to see him at the musuem. Theodora Kroeber herself brought out a kid’s version of her book in the 1960s, an inferior work that was required reading in 4th grade California classrooms for decades. I don’t remember hearing about Ishi in school, but rather through my Bay Area family. I know that Nana kept Kroeger’s book in her San Carlos library, because I nicked it. My dad just thought Ishi was cool.

Ishi was cool. But for all his dignity and good humor, not to mention his apparent lack of bitterness, we blow it if we simply bask in the man’s “humanity,” as if that universal affirmation can heal settler-colonialist guilt or elide the tragic binds that characterize indigenous relationships with whites in a white-dominated world. Ishi was, in the end, and sadly, object as much as subject, specimen as much as friend. Despite Ishi’s own wishes, his body was autopsied before it was cremated. Moreover, as if to add insult to insult, his brain was plucked out and pickled—an organic “artifact” that Kroeber, who had attempted to prevent the postmortem, nonetheless passed on to the Smithsonian.

In the 1990s, the anthropologist Orin Starn tracked down the the location of Ishi’s brain, a discovery that inspired a repatriation project that eventually returned Ishi’s remains, including his ashes, to the Sierra foothills. As the former UC Santa Cruz HisCon anthropologist James Clifford discusses, in a sensitive and comprehensive essay on Ishi in his book Returns: Becoming Indigenous in the Twenty-First Century, different indigenous groups wrangled over the details of Ishi’s reinterment, which was ultimately performed by the Pit River tribe. Besides reminding us that Indians are a diverse lot, capable of being as cantankerous as anyone else, the struggle reflected the continued power and presence of Ishi in postcolonial California. Kroeger’s iconic but overly sutured story in Ishi Between Two Worlds has now been picked apart into various threads that in turn contribute to different indigenous articulations of Ishi’s legacy: healer, survivor, teacher, trickster. As Clifford notes, if Ishi once symbolized the death of indigenous Californians, his return to the foothills demonstrates their ongoing vitality.

The anthopology museum is long gone from Parnassus Heights, but a psychogeographic trace of Ishi still marks our local land: that cave. It lies near a road and enviable university housing, but it’s unsigned, and nobody’s ever there. Who knows, maybe the story isn’t even true. I bring pals there sometimes, though it’s nothing spectacular. The cave is not much more than a cranny, and a stupid fence intrudes on the space, a barrier erected, with the usual sensitivity of our overlords, as part of a surveillance upgrade of the UCSF chancellor’s nearby stately home. The cave has a potent vulval vibe, but it sometimes reminds me of a wound. I usually don’t stay long.

Thanks for reading Vegar...some good local history!

Well done. Sensitive without being sentimental.