King of the Jinn

Esoteric Tourism in Morocco

Sometime it really pays off to be a perpetual student of religion and the occult. Travel, especially, can be unexpectedly transfigured if you equip yourself with a well-honed sacred radar, especially one tuned to animist and esoteric frequencies. With this sort of spirit-tech in hand, or in mind, even banal and hyper-touristy environments can pack a spectral punch.

I touched this truth again last June, when circumstances landed me in Morocco, with a few days on my own after the rest of my party had moved on to other climes. Morocco was the first new-to-me country I had visited in quite some time, and though you can hardly expect to go deep over a weekend, I was excited. That said, traveling on a tight schedule in an unfamiliar and popular “global destination” in the high season of the 21st century generally means a lot of research and booking beforehand. Covid and midlife drift have rendered unplanned travel a rarity for me. And the Internet, mobile phones, and the spread of signal have rendered it, perhaps, less possible in some objective fabric-of-space-time way.

With my Morocco dates approaching, all this boiled down to more time on the fucking Internet, rabbit-holing and credit-carding and adjudicating hustle and bullshit. Which also meant that I kept putting off the hassle until it was effectively too late. Out of some desperation, I turned to a friend of a friend named Jude, a woman who programs bespoke trips for a living. I characterized myself as a fan of religious sites who wanted to walk in rural areas and eat good grub but didn’t have enough time to travel far from Marrakesh. I hoped to hike to Tinmel, a gorgeous 12th-century mosque in the Atlas Mountains, and one of only two Moroccan mosques open to non-Muslims, but Jude told me it was closed for renovation. So I let that go and happily accepted her generous offer to design a quick package without her usual fee.

To make the most of my few days, Jude suggested a single driver-guide for the long weekend. Guides are a dice roll, of course. When I first met Ali in Marrakesh, I wasn’t sure if we were going to be able to establish a rapport. Broad, somewhat jockish, Ali spoke passable English, drove cautiously, and sported deep scars on his forehead, the aftershocks of adolescent rock fights that went down in the blazing village where he grew up on the edge of the Sahara. We chatted a bit but mostly drove in silence.

The first site he took me to, on our way out of Marrakesh, was Anima Garden, the work of a highly successful Austrian artist and German-language musician named André Heller. It was the second Moroccan garden crafted by a European I had visited in as many days, the first being the Majorelle Garden in Marrakesh, designed by a French Orientalist in the 1920s and restored over half a century later by fashionistas Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé. In contrast to the designer-sunglasses hordes crowding Majorelle—where the relaxed modernist style and copious use of blue, from succulents to enormous fired pots, recalled another famous Yves—Anima was nearly empty when I arrived. This allowed the coy whimsy of its sculptures, structures, and slogans to gently charm me until the Mittel-brow avant-pop circus vibe grew rank in the ever-present heat.

When I returned to the car, Ali was sprawled in the backseat reading the Qur’an, a multi-hued copy unzippered from a handsome leather cover. As we started the drive, I asked him about his faith and practice. I usually enjoy talking to people about religion, and find that my kind of curiosity tends to open things up. Ali described Islam in Morocco as “not too much bar, not too much mosque.” I remarked how fortunate it was that the country was not inflicted with Wahhabi, especially for the women, whose local choice to wear a niqab or the occasional burka he explained was just that: a choice. This led to a fascinating if unresolved conversation about how the essential unity of Islam, a core dimension of the faith, could be squared with its mutually contradictory interpretations, some of which Ali was happy to describe as “wrong” without condemning as actively false or heretical. Despite all its associations with absolutism in the West, Islam in many ways is less authoritarian than Christianity. For Ali, religious practice meant establishing a direct link to Allah and his prophet, following the pillars, living a good life, and not worrying too much about what other people think or do.

Attempting to share something of my own long strange trip with religion, I gave Ali a riff on my practice of tourism-as-pilgrimage. I wasn’t talking about highfalutin sacred travel here, just about my habit of visiting charismatic places that draw real pilgrims. In addition to feeding my fascination with belief, these sites attract tourists who are actually part of the show. Pilgrims may chatter and obsess over their phones, buy Cokes and trinkets, but they also reanimate the tourist groove with sacred desires and ritual intentions. This is a distinct improvement over the secular herds seeking packaged novelties and well-trod distractions to fill in the time between snacks and beer.

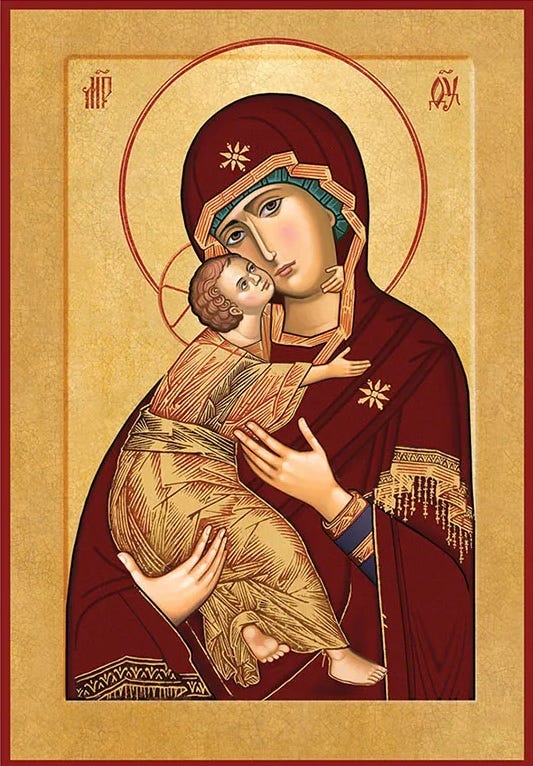

Tourism-as-pilgrimage is also an invitation to stay open to unexpected transrational encounters. I will never forget the cosmic portal that opened up one lazy afternoon in the Exeter Cathedral, as the blue mantle on an Orthodox Virgin of Vladimir icon melted into galactic black, a sea of stars that Stella Mara drowned me in for a divine minute or so. Zowee.

Of course, the sacred is in the eye of the beholder. I’ve also had convulsive epiphanies at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, the gritty bare-bones ruins of Eleusis, and a James Turrell Skyspace in Seattle. There is a lesson in this for the sacred tourist: the entire earth is filled with portals.

Nor must such encounters trigger sharp convulsions to shift your field. I am still nursing the vibe of a marabout shrine south of Algiers I visited in the late 1980s. Marabout is a Maghreb term for saints, or sidis, usually Sufi, sometimes scholarly and sometimes wild. I don’t know anything about the saint whose tomb our crew visited that afternoon, but I felt like I was walking into the antechamber of an elegant folk heaven. Women and children sat casually on the floor, praying for healing and blessings, or just enjoying each other’s company. Despite the central presence of a sepulcher, the place radiated life, verdant energies that are stitched into my memory with green thread, green being the shrine’s dominant interior color. It’s a familiar enough color to frequenters of mosques, but it was my first taste of an Abrahamic hue outside the bloodier and more regal stains of Christendom, and it felt like spring.

With that encounter in mind, I asked Ali whether it would be possible to visit any marabout shrines during our weekend together. Ali thought a moment, revising his route for the next day’s hike, and smiled.

That afternoon we drove into the Imlil Valley in the high Atlas Mountains, which a seasoned traveler I know had warned me to avoid. As we passed Richard Branson’s high-dollar Kasbah Tamadot, I understood why. Imlil is also the main access point for Toubkal, at 4167 meters the tallest mountain in the Arabic world, and it attracts tons of trekkers whose numbers visibly increased as we drove up the valley. That night I found myself at a hobbity hotel in the steep village of Tamatert, my tiny cabin room perfumed with the honest funk of nearby beasts.

Next morning’s walk started promising enough. Ali and I left Tamatert along winding and old cobblestone paths half covered with irregular concrete slabs, passing old Berber women lugging massive bundles of hay. The cherries were in season, and they hung in the orchards like pendant rubies. The night before I had learned the name of the shrine’s occupant, Sidi Chamharouch, and I asked Ali what he knew about the saint. Not much, Ali said, though he did know that Chamharouch was also considered to be King of the Jinn.

King of the Jinn?!! My eyes almost popped out at this sudden swerve towards eldritch lore. Though I hadn’t studied much about Jinn—the genies most westerners first encounter in the Arabian Nights—I did know that they were invisible creatures that Allah fashioned from fire at the beginning of things, alongside Adam but not partaking of his clay. These preternatural agents also play an important role in Islamic folklore and magic—and I have a grimoire to prove it. They are no strangers to players of D&D as well.

But what are such creatures doing in a shrine? Ali was a modern-minded Muslim, and believed that jinn referred to a largely psychological range of phenomena, rather than actual entities. To dig out more fantastic lore, I asked about any jinn stories he heard growing up. The jinn are easy to offend, he explained, which is why some Muslims do not throw away hot water—remember the fiery origin of the creatures—but allow it to grow tepid first. Ali also explained that there are Muslim jinn and unbelieving jinn, but that both might get on your ass, producing symptoms that can resemble mental illness. Sometimes jinn punish disrespectful or immoral behavior, but they are also capable of inflicting vengeance for unintended ills, like throwing a rock aimlessly over some wall, where it might do harm you are neither aware of nor intend.

I was feeling good now. The esoteric jam was on. The gummy didn’t hurt either. Passing through cherry orchards on the outskirts of another village, we entered a wide and rocky river plain. And there my heart sank. The one path from the Imlil villages towards Toubkal was thronged with trekkers, each pod led by a local guide. As Ali and I merged into the stream of bodies, I felt like I was slotting into a mechanical track, my silly sense of discovery dissolving into a Patagonia ad. The title of a travel book that the activist and humorist Andrew Boyd once considered writing came to mind: Wherever You Go, They’re Already There.

The milling hordes can really harsh my mellow. When all of us hikers reached a trailside police station we stopped to have our identification checked, and listening to the conversations of my fellow travelers I recognized the tourist honeytrap I had fallen for that morning, the one that flashes novelty and delivers banality. As the world colonizes its own cultural and geographic differences, integrating them into circuits of desire, consumption, and digital exposure, it gentrifies everything not unlucky enough to become a disastrous no-go zone. It’s hard to shake the sense that hypermediation depletes the substance of the world. The lure of travel may charm, but the more the path is pampered for convenience, with Tripadvisor recs, WiFi, and credit swipes, the easier it is for us to never really leave home. I was relying on these circuits as much as anyone, but many of my fellow trekkers didn’t even seem to be trying to avoid the tractor beam of the predictable.

Hell, we weren’t even having the “authentic experience” of waiting around in border control offices, with their vague ambience of threat. Instead, we waited outside as the guides took care of the paperwork. Occasionally we had to step off the path to make way for mules, which my stoned head initially presumed were shuttling local goods between villages, as they had for centuries. But the beasts were only loaded with backpacks and rolly bags, so that the trekkers would have all their stuff at the high-elevation camps.

Once I got my documents back, I dropped the topic of jinn and asked Ali about his job. After growing up in a small Saharan village, he moved to a Berber mountain town, where he started to fall into delinquency until a couple of kind teachers helped pull him out of a downward spiral. Later he decided to become a mountain guide. Unlike the more ubiquitous city guides, mountain guides face a grueling training program that sounded like boot camp, with plebes routinely hiking 20 miles through difficult terrain before setting up camp and cooking meals. Though an injury had set Ali back for the last few years—precarity knows no borders—he was making a living again, and hoped to soon move his wife and parents from their village to Marrakesh. I asked him if he had any concerns about Morocco’s flourishing tourist trade. Yes, he said. He had seen young people in some villages developed for tourism dramatically change their values and behavior, and that worried him.

As we followed the crowds up the mountain path, I started to check out the other guides. I was impressed with the sartorial flash of the younger men, who were of a different generation than Ali. A number sported a particularly groovy style of sneakers, a grooviness that spoke directly to the globalized cultural framework that allowed both them and me to perceive the shoes that way. It felt like a shared sensibility, and a common stain.

Once or twice we passed a different sort of traveler on the trail: pilgrims coming from the shrine of Sidi Chamharouch. Soon the path converged with a tumbling and rocky river bed before clambering up across another escarpment. The cluster of buildings surrounding the shrine seemed mostly empty when we arrived. One or two restaurants on the outskirts were feeding trekkers, but most folks kept hiking, leaving the souvenir shops and tea stalls largely shuttered. From where we stood, a bridge passed back over the bubbling water, on the far side of which lay the large whitewashed boulder where the sidi was entombed. A small building was built directly onto the stones, and this shared a wall with an only slightly larger mosque. All these structures were off limits to non-Muslims, a prohibition first codified by the French.

As we approached a sitting area on the near side of the bridge, Ali offered to ask some locals to talk about the shrine and translate for me. It was a kindness I trace to my respectful curiosity about religion. We first met a tea seller, a man bedecked in crisp Moroccan football attire, including an excellent trucker hat that I instantly coveted. He didn’t say much about the saint, but eagerly told his own story. He came from the city, where he had a family before his wife left him and took the kids. He said he was crying all the time, presumably not just from the divorce, but from whatever malady had already been eating at him and causing strife at home. His sobbing and grieving got so out of hand that he spent months at a mental hospital, taking pills and receiving injections. Nothing helped.

Out of desperation, he came to Sidi Chamharouch and was relieved of his suffering. (I neglected to ask how he found out about the shrine; later I learned that some pilgrims get directions from dreams.) After returning to the city he realized that he felt better near the shrine, so he returned and set up a tea shop for trekkers and pilgrims. He seemed happy and energized, but he vibrated like a live wire, with the forced overenthusiasm one sometimes senses among folks in recovery.

After sitting down to drink some tea, Ali hunted down the main poobah of the shrine complex. The man joined us, sitting down with a cup of coffee. He had a kind face, open and slightly sad. He had lived and worked there for over half a century, treating the jinn-damaged as his father had before him. I forgot to write down the name of this wonderful man, and Ali couldn’t remember it later, though he did text me some English terms for the guy’s job: healer, shrine guard, and, most interestingly, juggler—a now antiquated term for a practitioner of prestidigitation and the magic arts.

The shrine guard clearly drew some of his power from his way with words. He knew his story like the back of his hand; it rolled out of him without interruption, only a small portion of which Ali was able to translate and summarize. The man said he basically ran a hospital, by which he meant a mental hospital, since the jinn vexings lay largely in the realm that we might dub “psychological.” As Ali had explained before, there were different reasons people got saddled with vengeful jinn. Sometimes it was payback for moral failings, but other times it was nothing more than ill luck, the wrong place at the wrong time.

“Possession” is a heavy-duty word in pop culture—where it suggests demons, which jinn decidedly aren’t—and in anthropology, which today often prefers the less stigmatizing “incorporation.” I doubt possession is the right word here. For one thing, the treatment seemed less like an exorcism and more like a conversation. As the shrine guard explained, clients are invited to sleep in the shrine room, while the Qur’an is chanted over them. Then the healer directly addresses the jinn, who respond, as far as I could tell, using the client’s vocal cords. The healer first tries to reason with the interlopers, asking them to forgive the client and offering up Qur’anic prayers as part of the influence campaign. With recalcitrant jinn, things become more complicated. Here the difference between Muslim and non-Muslim jinn became an important explanatory principle, since the Qur’an obviously doesn’t work on unbelievers. But rather than banish or excoriate such infidels, the healer’s job is to instead convert them to Islam. Since this sometimes takes a while, some clients are housed in a nearby structure, divided into men’s and women’s quarters, that abuts the cold mountain stream. Here the jinn-damaged can plunge in the no doubt revivifying waters and maybe shock the fire creatures out of their systems.

There was a lot more but I missed it and even what I have included here I am sure could be fact-checked further. When I started to write up my notes after returning to the States, I settled into one of my happiest places, which is researching arcane topics. But I soon gave it up, preferring to stick to what I learned at the time. I couldn’t find much about a marabout named Sidi Chamharouch anyway, at least not without some interlibrary loans. I did stumble across a scan of an 18th century grimoire on a random jinn wiki that included a talisman for “Shamhurish,” a jinn king associated with purple, Thursday, Jupiter, and tin—common esoteric correspondences to the ruler of the gods. Then it hit me: Sidi Chamharouch might not be a human at all, but himself an invisible being of fire.

I left our juggler with a small token of appreciation, but whether from shyness, respect, or a surfeit of satisfaction at the bubbling pot of esoteric tea I had just enjoyed, I neglected to ask for a photo. I wish I could share the image that is in my head: this seasoned spiritual expert, with his sad smile and casual confidence, set against the high Atlas Mountains and a nearby flock of strange corvids with yellow beaks. These alpine choughs also had something to do with the jinn, but I couldn’t get to the bottom of it. Maybe the jinn hop from the humans to the birds? In any case, it was considered a blessing to feed them, so they were having a grand old time fluttering about the shrine with their slightly comical banana bills.

Following tea, Ali and I started back on our descent. The path was now nearly empty of trekkers, which meant relief from the ceaseless tourist chatter. I could tune into birdsong and the distant plashing of the stream below, all of which conjured enough serenity of mind to really take in the beautiful cedars and junipers of these fine mountains, so similar to the High Sierra trees of the Burning Shore back home.

Reaching the village of Armed, we stopped for lunch at the home of a man Ali knew who worked at the local hammam. El Houssine invited us into a clean stone warren centuries old. His vegetable tagine was simple and delicious, his vibe friendly and dignified, and his young daughter cute as a button. During lunch I asked the man, who dressed traditionally, what he thought of the shrine. Jinn are mentioned in the Qur’an, and belief in their existence is widespread in the Muslim world. But the sorts of popular healing practices taking place up the mountain were hardly orthodox (nor are marabout for that matter). El Houssine said the imams in Imlil Valley were divided on the topic of the shine, and he didn’t think much of it himself. Here, as always, there are two main categories of complaint: religious ones—jinn healing is heretical or at least unsanctioned—or rational ones—the whole thing is kinda bullshit. El Houssine seemed to be of the latter school, but was too mellow to get worked up about it.

Back in my hobbity hotel that night, after chitchatting with fellow tourists, I reflected on the gentle liminal zone Ali had brought me to that day. Not just up and around the mountains, but into the margins of a Berber ontology that allowed me to sidestep the tourist track. A whitewashed boulder and a dusty tea shop were woven into a nexus of healing, pathology, jugglery, and negotiations with the non-human, a cluster of features whose esoteric overtones were at once enchanted and terribly familiar. It was the old high weirdness again, that porous continuum between here and there, everywhere you go.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. These pieces and updates come when they do, and I dodge the stress of the hamster wheel by not offering paid subscriptions. But you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

I am sure that there are problems, but my impression is that Morocco is a very safe place to travel. One good side of having such a robust tourist industry is that everyone is pretty interested in keeping things mellow, but there are still many areas that are less "routinized". At another point in my trip, I had the opportunity to visit a public hammam in a provincial town with no real tourist industry. My guide that day was a woman, so she just pointed me to the entrance, where I fumbled around taking off my clothes and putting them in a cubby before entering another room and bumbling around until somebody started lathering me up with the delicious mudstuff they use on your skin. At one point I was sitting there and realized that my wallet with all my cash and my passport was sitting there in an open cubby when all sorts of dudes saw me come in. But then I thought, "hey this is a provincial town, and all these dudes are Muslims." I could have been wrong of course, thieves are everywhere, but I chilled out and everything was fine.

Indeed. That is a very cool book. One problem with today's idolization of "shamanism" inside psychedelic healing is that it ignores all the many non-psychedelic forms of indigenous healing that are equally wild and colorful, and clearly effective (or it wouldnt keep happening all over the world). Some of the Bruno Latour material I use in High Weirdness came about because of his exposure to indigenous (probably African) healing practices now found all over Europe.