Myths and Matters

Californica and More

August should be a mellow month, but that hasn’t stopped me from working hard on Weird Hunter, my forthcoming career-spanning essay collection, to be published (Goddess knows when) by Strange Attractor Press. It’s also really lovely outside. So in lieu of a fatty essay I herewith offer up another plate of Californica and news ‘n’ notes.

Upcoming Events

• Practice Circle. This Saturday, August 16, at the Berkeley Alembic, from 2 to 4 pm, I will once again host a conversational workshop about the practicing life with my squeeze Jennifer Dumpert. Everybody talks about “practice” but what do we mean by it? What are the features and traps of being a practitioner? Rather than focus on particular practices, the Circle offers room for us to discuss the sometimes difficult issues that arise around practice in general — issues like commitment, guilt, obsession, intuition, experimentation, trust, rejection. Suggested donation, $20-40, no one turned away. Registration here.

• 3rd Ear Presents: Fletcher Tucker performing Kin. This amazing show will take place Saturday, August 16, 6:30 pm, also at the Berkeley Alembic. Join the Big Sur musician, Gnome Life Records label head, and wilderness junkie Fletcher Tucker for a rare live performance celebrating the release of his new album. Composed while trekking through the remote Big Sur back country, Kin is a sonic offering to the living world: an incantation of kinship, mystic communion, and mythopoetic storytelling. Tucker’s immersive set will bring to life the record’s elemental palette of “ancestral instruments” — pump organ, Swedish bagpipes, flutes, and bowed zithers — alongside chanted verse and percussive portals to the liminal.

The opener for the evening will be LFZ, the exploratory sound project of Los Angeles–based artist Sean Smith. Together, these two visionary artists will unfold a night of vibrational ceremony and sonic enchantment. At the end of the evening, I will moderate a discussion with Tucker about his animist approach to culture-making. Deets here; $20-$50, but no one turned away for lack of funds.

Californica

• LD Deutsch, Time, Myth and Matter. There is a vast modern literature that attempts to build bridges between science and spirituality — quantum mysticism, paranormal theory, and far too many retellings of Kekulé’s ouroboros dream. California is responsible for a lot of this stuff, much of which is profoundly unsatisfying, if not actively crappy. In her wonderful essays, which were first published as chapbooks by LA hepcat label Sacred Bones and now gathered into a beautifully designed book, the Los Angeles writer LD Deutsch takes another tack. Carefully, with deep research and bright, illuminating prose, Deutsch traces the points where the narratives of science and myth diverge, echo, and assemble themselves into genuinely new patterns of understanding. She can discuss physics with clarity, respect, and rigor, but like the first wave of quantum theorists, she allows herself to move deeply into philosophy, myth, and the mystery of consciousness. She is not, in a strict sense, a physicalist. And yet, when she does wrestle with uncanny things, like gods and oracles and synchronicity, she does not sink into the typical archetypal Jungiana. Every line of her book is devoted to the clarity and discrimination and serious joy required to trace the cracks and zig-zags and fluttering ripples in our weird conundrum. In fact, I believe she is incapable of writing a New Age sentence. Instead she does the hard work of getting to the heart of the matter of the mystery.

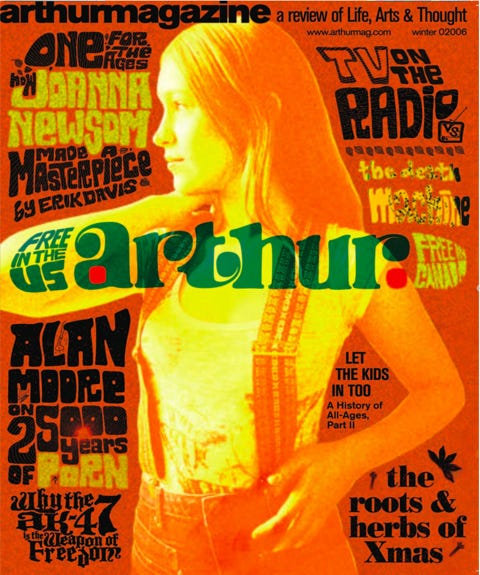

• Arthur Scans. Arthur magazine was the last print publication I wrote for regularly, the last general publication I identified with, and probably the last one that I really cared about. A creature of Los Angeles, Arthur was principally associated with music, especially psychedelic rock, freak folk, and all manner of spiritual riffs. But it also worked hard to sustain and nurture a sense of organic subculture that was being squeezed out of existence. I wrote a column for a while called “The Analog Life” and also penned a monster cover feature on Joanna Newsom and Ys.

As someone who came of age writing for classic alternative newspapers like the Village Voice and the LA Weekly, I have always appreciated (and, later, mourned) the way that print publications can weave themselves into the material life of a city or a culture or a scene. Arthur ranged too widely to fit into a narrow demographic, but it did have a consistent local vibe, an Angeleno sense of mystery and bluster that was at once crunchy and spiky and leafy and down-to-earth. Its consistency was due in no small part to the visionary leadership of its indefatigable editor and co-founder Jay Babcock, who currently pens one of my favorite and most consistently read Substacks, the informal but deeply nourishing Landline.

Arthur ran through most of the 2000s, and then returned in a different but still satisfying format from 2012 to about 2014. I was sad to see it go. So I was incredibly pleased to learn that the complete run of the magazine has been scanned, OCR'ed, indexed, and made searchable by the hardcore archivists at Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale (RILM). The Arthur page is part of their recently launched “Archive of Popular Music Magazines" (RAPMM) collection, which the RILM describes as "the ever-expanding full-text compilation of zines that facilitates unprecedented federated searches.”

Huh? As you might guess, RILM is an institutional joint, a subscriber-based operation geared (and priced) towards universities, research institutions, libraries and so forth. While that’s great for Arthur’s legacy, as well as future researchers, it’s not necessarily helpful for you or me. Luckily, drawing from both scans and the original digital files, Jay has also recently posted pdfs of every single issue on the Arthur website. Whoopee!

• Lost Coast: Some Visionary Music from California, 1980-1992

This extraordinarily pleasing compilation of obscure and charming private press recordings from the Golden State is so deep in the Burning Shore pocket that it rips out the other side like a meteorite plunging through the exosphere. These cosmic and spiritually-minded tracks were made during the golden age of Golden State New Age. But they only really bounce along the boundaries of that genre, and from different angles to boot: Martin & Scott’s “African Sweet Fantasy” starts out with ET chimes and Native flutes but veers towards diaphanous dissonance, while Clay Play’s “Ancestress” sounds like the ambient B-side of an industrial track that mutates into an indigenous Scots-Irish chant fantasy. There are avant-garde sine waves, zithers by the sea, and a lovely song with words entitled “Song Without Words.” Welcome the low-fi divine.

Many of these tracks are so obscure they still carry the penumbra of transience with them, like the last glow of sunset that somehow got bottled against oblivion. They were gathered by Zully Adler, the overlord of the cassette label Goaty Tapes, known for informal experiments, four-track wanderings, and bedroom pop, recordings marked with a rare quality of intimacy and enchanted scruff. Reflecting a similar spirit, the tunes on Lost Coast were produced far from the circuits of commerce and broadcasting — DIY gifts of and for the spirit. They were sourced from private collections, estate sales, flea markets, and thrift store trawls. Some tracks here were composed for yoga classes or ceramics studios, and one was sourced from the collection of a former mescaline dealer near Eureka.

Adler met the guy because he used to know Martin Wong, a wonderful and sometimes visionary California-to-New York Chinese-American freaky queer artist whom Adler wrote about for his dissertation at Oxford. Wong is a fascinating character, and Adler has the chops to relate his work to the various subcultures the man moved through, including Haight Street freakdom (Wong was in the Angels of Light). I thoroughly enjoyed the Cali parts of Adler’s dissertation, and am happy to report that he is currently turning the manuscript into a book.

Adler can rock the artcrit speech, but he knows the vibe of the underground from the inside, and is a damn fine curator to boot. You can catch a whiff of his care in this interview about Lost Coast. One of the major concerns for creative curators is context — what brings a collection of items together, what sort of story or “category” does it imply, how does it crystalize a larger network of associations, forms, realities? Regarding Lost Coast, Adler notes that:

Each recording is stylistically different — dream pop, guitar soli, fourth world, avant-electronic — but they are held together by a regional ethos of the “visionary.” This is music that sees through the mind’s eye and conjures new worlds. […] Some people say that California is where “the nuts stop rolling” — where those too eccentric to fit in elsewhere often find themselves. What was meant pejoratively is easily reclaimed as a celebration of the free-thinking and the freely-freaking. Until the turn of the millennium, all manner of seekers rolled westward until they hit the pacific. Stationed along this edge, music was a way to roll still further, imagining territories unencountered and wavelengths as yet unheard.

Notice that Adler does not say “New Age.” The problem with the latter category is that, like so many well established designations, it shuts down as much as it clarifies. By preferring the broader and less defined “visionary,” Adler lets us hear these sorta New Age pieces in a new and different light. He has assembled a uniquely shining crystal that in turn tunes and refracts the larger psycho-history of California’s sacred experimentalism, its peaks and valleys lost and found and lost again, but then dug out of a pile at a yard sale in McKinleyville.

Appearances

• ICPR Interview. I met Péter Sárosi and his fellow Hungarian “drog riporters” at the Open Foundation’s Interdisciplinary Conference on Psychedelic Research in the summer of 2024. Blotter had just been published, I was prepping intensely for my keynote address, and my mind was filled with reservations about the cultural, psychological, and spiritual costs of the mainstreaming of psychedelics. The field of psychedelics has changed a lot in the year since, but I still feel swell about this interview and the intelligence of the Drog Reporter team (except for some creative misspellings of my name, including the “Eric” that dogged the first printing of Blotter).

• Dharma and the Dead. While the Grateful Dead need no more smoke blown in their direction, from hash pipes or from hagiographers, it must be said that the 60th anniversary Dead and Company’s shows at Golden Gate Park only further knitted the Dead’s legacy into the texture of San Francisco, the Burning Shore, and our now terrifying America. Legacy is maybe not the greatest reason to go to a show, but thankfully the Nameless Mystery was still prowling about amidst the poster tubes and corn dogs, providing galactic boogie and heartfelt devotions alongside a number of questionable musical moves and the steady flow of dollars into the pockets of promoters inside and nitrous dealers outside (“Cold ones! Get your ice colds!”).

Didn’t matter to me: I was happy dancing my prayers. Wandering through the polo field before the show on Friday night, I knew immediately that the Cosmic Dancers would gather behind the windmill thingee, where the sound was good but you couldn’t see the stage. And indeed they were there, the whirling, spinning, bone-dancing initiates, my new and ancient friends. At one point I felt a disturbance in the force, and made a Good Samaritan beeline towards the scene: some yellow-vested security folks surrounding a middle-aged woman in full freak-out — half nude, lunging around in awe and terror, eyes alight with strange shadows. I caught her gaze and, despite my pragmatic orientation toward harm reduction, realized that she was deeply in trance, swallowed up in a nightside of spiritual ecstasy she had reached at the extreme end of a visionary protocol — drugs, dancing, worship, who knows — that she probably did not expect would take her quite this far. Luckily she was surrounded by friends, and the yellow-vested kids were mellow. I don’t know where they led her away to, and I dearly hope that Another Planet Entertainment provides some sort of decent psychedelic support at this point (though I doubt it). But at least she was surrounded by kindness and care.

This encounter reminded me, once again, of the sacred stakes of Deaddom, devotional, risky, and sublime. Before the shows, Jamie Wheal and I gave a presentation at the Portal in Mill Valley about the initiatory powers and feral wisdom of the band, and particularly their matchless songbook. In different but complementary ways, Jamie and I were really trying to grapple with the paradoxical religiosity of the Dead’s profane illuminations. We weren’t just high on nostalgia. We were interested in how the Dead phenomenon — the jamming, the lyrics, the ethos of Americana, the cosmic synchro-syncopation — all helped provide qualities of collective play, cultural resonance, and integration that our current psychedelic renaissance, with its AI guides and corporate takeovers, could certainly use. During Q&A, Rose Barlow, the daughter of Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow, pushed back on some of our rosier views with straight talk about the inner scene’s narcissism and foolishness. But she did insist that the core ethos was well captured in that line from “Uncle John’s Band”: “Wo-oh, what I want to know is are you kind?"

Not sure if our discussion will ever be posted, but Jamie and I were both pleased with this clip of Bob Weir talking to Dan Rather about the “American Zen” of Hank Williams. He also makes the core interpretive point that religion and non-religion are both legitimate approaches to this American Zen current, a current that really is bound up with an American ethos that, I am afraid, is effectively dead and gone, but therefore, at least possibly, still Dead.

I dove into the band’s American Zen more directly for a San Francisco Zen Center workshop I did last weekend with the Zen teacher Kokyo Henkel. Kokyo is a delight — sharp as Manjushri’s sword, twinkly-eyed, and ever so slightly goofy. In the late 80s, Cosmic Charlie — as he was then known — racked up a couple hundred shows on tour before making his way to Tassajara monastery. Earlier this year, Kokyo participated in the Psychedelic Sangha’s Psychedelic Buddhism 2025 conference, but we didn’t talk about drugs directly. We had a great time going through our favorite tunes, and riffing on words and meanings, emptiness and form. SFZC kindly made our three-hour conversation available at this link. If you like the idea of studying Zen with a Deadhead, you can explore Kokyo’s website or visit his Bright Window hermitage. You might see clear through to another day.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. More than anything, I want to resonate with readers out there. So if you want to show support, the best thing is to forward my posts to friends or colleagues. You are also welcome to consider a paid subscription, and you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

Always inspiring jazz from you Erik. Love your delivery. Got the same buzz-nature as RAW. Happy Trailz. 😊⚛️👽🕉️🚀

Jealousy and envy are two threads that would be interesting to examine as practice barriers. I'll contemplate this tonight under the Black Moon while experiencing the soul stirring magic of David Guetta on his Monolith Stadium tour in Tallin Estonia.