Today, February 20, is the (possible) fiftieth anniversary of that strange day when Philip K. Dick glimpsed a delivery woman’s Christian fish necklace and launched into the extraordinary series of bizarre experiences and events that the author referred to as “2/3/74.” Lawrence Sutin gives us this date in his bio, but I don’t know where it comes from. Today is also the last gathering of my Alembic lecture series on The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. The date lies heavy, it seems.

So for this “One from the Archive” (new slug) I decided to repost some excerpts from a Dick essay I first ran on the nettime listserv on September 25, 1996. (For the full version, plus citations, see Techgnosis.com.) In the 1990s and 2000s, nettime was a wonderful and spiky gathering place for media artists, tech critics, theory heads, and avant-garde hackers. I owe a profound debt of gratitude to the collective insights, grumpy comaradery, and social and critical possibilities catalyzed on that important listserv, whose sharp and radical European voices countered the dominant voices of American and especially West Coast tech speculators (in both senses of the term) in those years.

When this essay ran, few Dick critics were really engaging the man’s religious experiences, something I wrote about for my Yale thesis in 1988 and would discuss in Techgnosis two years later and, two decades later, in High Weirdness. Attentive readers will recognize some language and arguments from those texts, but there is enough unique stuff in here — particularly the discussion of Three Stigmata and Jean Baudrillard, whose revival is seriously overdue in these AI daze — to beam it to you on this uncanny anniversary.

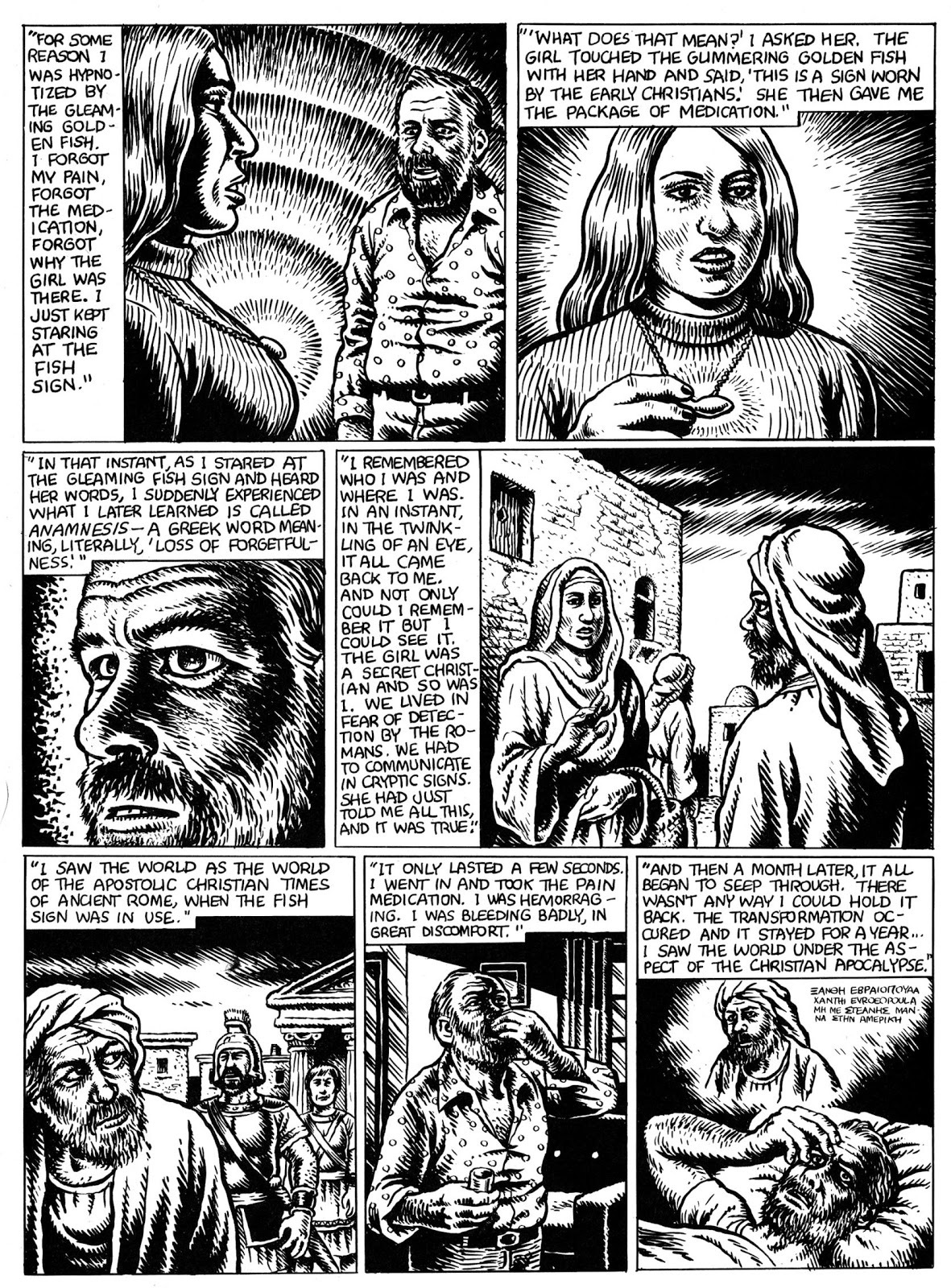

It was February of 1974, and the American science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick was in pain. The man whose darkly comic novels of androids, weird drugs, and false realities stand as some of the most brilliant and visionary in the genre had just had an impacted wisdom tooth removed, and the sodium pentathol was wearing off. A delivery woman arrived with a package of Darvon, and when the burly, bearded man opened the door, he was struck by the beauty of this dark-haired girl. He was especially drawn to her golden necklace, and he asked her about its curious fish-shaped design. “This is a sign used by the early Christians,” she said, and then departed.

Most of us who hit the freeways in the U.S. know this fish well, as its Christian and Darwinian mutations wage a war of competing faiths from the rear ends of BMWs and Hondas. As a Christian logo, the fish predates the cross, and its Piscean connotations of baptism and magical bounty (the miracle of loaves and fishes) reaches back to the time when the harshly persecuted cult secretly gathered in the catacombs of Alexandria. Ichthus, the Greek word for fish often inscribed within the symbol, is also a code, an acrostic of the phrase “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.” One apocryphal story claims that Christians would secretly test the spiritual allegiance of new acquaintances by casually drawing one curve of the fish on the ground. If their companion was “in the know,” he or she would complete the fish shape.

For Dick, the ichthus was a secret sign of an altogether different order: it was a trigger for gnosis. As he wrote later in a personal journal,

The (golden) fish sign causes you to remember. Remember what?…Your celestial origins; this has to do with the DNA because the memory is located in the DNA…You remember your real nature…The Gnostic Gnosis: You are here in this world in a thrown condition, but are not of this world.

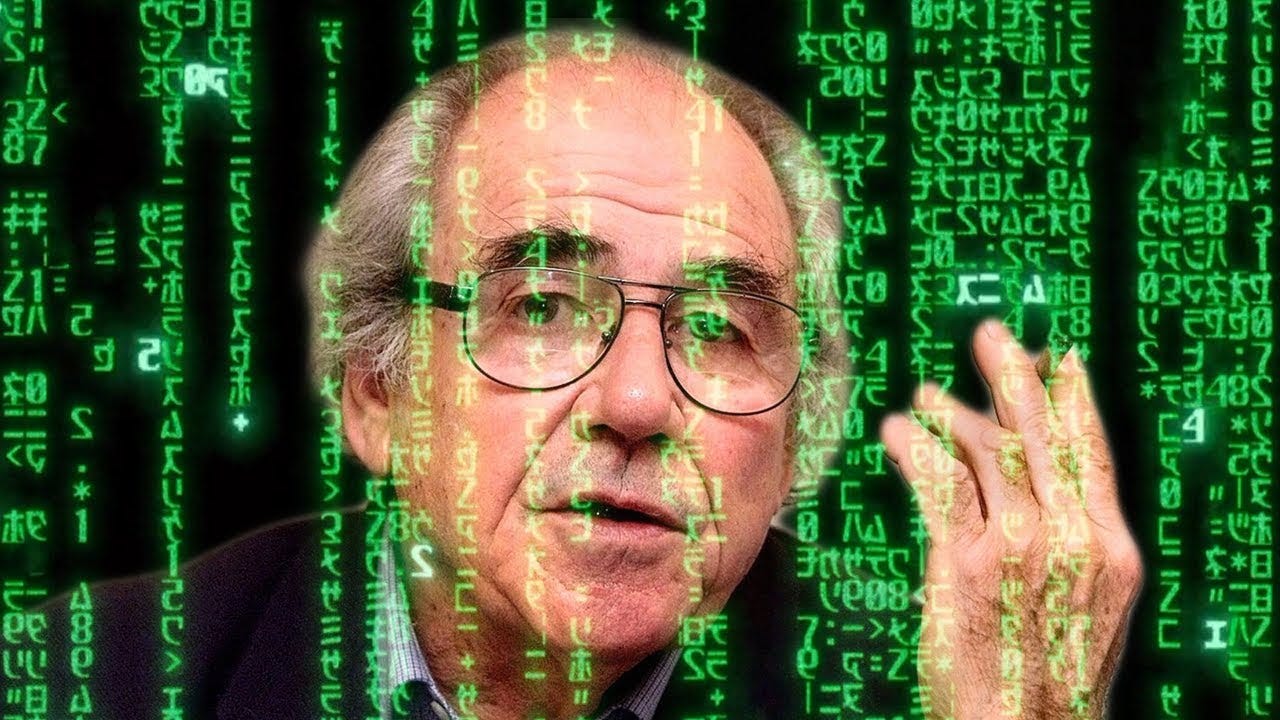

Following this event, Dick experienced a remarkable series of visions, hallucinations, and dreams, many of which centered around VALIS, a “Vast Active Living Intelligence System” that he defined in his 1980 novel of the same name as a “spontaneous self-monitoring negentropic vortex…tending to progressively subsume and incorporate its environment into arrangements of information.” Not a bad definition of the Internet, though Dick experienced this incoming information web far more intensely than today’s online grazers. Sometimes it struck him as a pink beam of esoteric data, or as a compassionate feminine “AI [Artificial Intelligence] voice” speaking to him from outer space. Other times, Dick felt he was in telepathic communication with a first-century Christian named Thomas, and once “the landscape of California, U.S.A. 1974 ebbed out and the landscape of Rome of the first century C.E. ebbed in.”

Like many an acid casualty (Dick himself preferred amphetamines), Dick also picked up strange signals from electronic devices, and for a time he received “die messages” from the radio. This should be no surprise; radios, stereos and TVs feature prominently in a number of his novels, where the war of signal and noise often takes on metaphysical connotations. But Dick’s paranoia could turn itself inside-out and become divine intervention, and once when listening to the Beatles’ “Strawberry Fields Forever,” the strawberry-pink light informed him that his son Christopher was about to die. Rushing the kid to their physician, Dick discovered that the child indeed had a potentially fatal inguinal hernia, and was soon wheeled into the operating room.

Many more fantastic events played themselves across Dick’s nervous system, and he would sometimes refer to the whole barrage simply by its date, “2-3-74.” As Dick himself recognized, 2-3-74 avails itself equally to the language of religious experience and psychological pathology. And yet the events seem too fractured for the one, too resonant and rich for the other. As has often been noted, 2-3-74 reminds one of nothing so much as the ontological paradoxes of a Philip K. Dick novel, where the spurious realities that often surround his characters can collapse like cardboard in the face of disruptive information coming from another order of reality beyond the local simulation. Even if Dick underwent something like a temporal lobe epilepsy (which Lawrence Sutin argues is the most likely somatic explanation), earlier books like Ubik, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch and A Maze of Death provide more than enough evidence that 2-3-74 erupted from his own creative daemon.

Besides, Dick himself could never make up his mind about what happened to him, his broiling considerations of the matter clipped only by the stroke that ended his life in 1982. Besides weaving elements of 2-3-74 into a number of novels, including the masterful VALIS, Dick cranked out what is known as the “Exegesis” — a couple million mostly handwritten words that restlessly elaborate, analyze, and pull the rug out from under his experiences. To judge from those portions that have seen the light of day, the Exegesis is an alternately incandescent, boring, and disturbing document, where sparkling metaphysical jewels and inspiring chunks of garage philosophy swim in a turgid and depressing sea of speculative indulgence and self-obsession.

Unlike most religious seers, Dick did not approach his visions with anything like certitude. Dick distrusted reification of any sort (his novels constantly wage war against the process that turns people and ideas into things), and so he refused to solidify his experiences into a belief system. Like William Blake, another impoverished autodidact whose bubbling imagination was steeped in the Western visionary tradition, Dick approached his theophany (or “in-breaking of God”) as artistic material, reworking it in his writings with an artist’s commitment to irony, craft, and a political bite. Even in his private journals, he constantly liquefies his revelations, writing with a modern thinker’s sense of the tentativeness of speculative thought. “Indeterminacy is the central characteristic of 2-3-74,” writes Sutin in his Dick biography Divine Invasions. Sutin points out that mystics traditionally interpret their experiences within the faiths they are raised in. “Phil adhered to no single faith. The one tradition indubitably his was SFwhich exalts ‘What IF?’ above all. In 2-3-74, all the ‘What IFs?’ were rolled up into one.”

In the excepts of the Exegesis reworked into the “Tractates Crytptica Scriptura” that close the novel VALIS, Dick expresses the MIT computer scientist Edward Fredkin’s view that the universe is composed of information. The world we experience is a hologram, “a hypostasis of information” that we, as nodes in the true Mind, process. “We hypostasize information into objects. Rearrangement of objects is change in the content of information. This is the language we have lost the ability to read.” With this Adamic code scrambled, both ourselves and the world as we know it are “occluded,” cut off from the brimming “Matrix” of cosmic information. Instead, we are under the sway of the “Black Iron Prison,” Dick’s terms for the demiurgic worldly forces of political tyranny and oppressive social control. Rome is the eternal paragon of this “Empire,” whose archetypal lineaments the feverish Dick recognized in the Nixon administration.

Just as William Blake condensed the coming horrors of industrialism into his image of “Satanic mills,” Dick’s Black Iron Prison imaginatively captured the “disciplinary apparatus” of power analyzed by Michel Foucault. Demonstrating that prisons, mental institutions, schools, and military establishments all share similar organizations of space and time, Foucault argued that a “technology of power” was distributed throughout social space, enmeshing human subjects at every turn. Foucault argued that liberal social reforms are only cosmetic brush-ups of an underlying mechanism of control. As Dick put it, “The Empire never ended.”

VALIS invades this spurious world of control in order to liberate us. For Dick, this “living information…replicates itself — not through information or in information — but as information.” VALIS is a virus, a kind of metaphysical DNA that encodes the Logos or “Word” that opens the Gospel of St. John. Birth from the spirit occurs when the information plasmate “penetrate(s) the world, replicating in human brains, crossbanding with them and assisting them…” Dick calls these hybrid humans “homeoplasmates”. At one point Dick believed that when the last of the homeoplasmates were killed off with the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans in 70 C.E., “real time ceased.” The plasmate reentered human history in 1945, when jars stuffed with ancient gnostic codices were discovered in Nag Hammadi, Egypt.

In order to snake its way into the Black Iron Prison, “the true God” must mimic “sticks and trees and beer cans in gutters.” Dick’s God “presumes to be trash discarded, debris no longer needed,” so that “lurking, the true God literally ambushes reality and us as well.” Here Dick suggests a kind of liberation info-theology, a set of guerrilla tactics for our saturated data age: stick to the fringes of the spectacle, pay attention to marginal or discarded information, and never let your beliefs get in the way of surprise. Dick knew well that the political and metaphysical search for secret orders of power invites the black iron prison of paranoia, but he also recognized that “Surprise is an antidote to paranoia.”

Dick was well aware of the nuttiness of 2-3-74, and when he turned to the problem of narrating the event in VALIS, he split himself into two characters: the narrator, a sober science-fiction writer named Phil Dick, and a mad visionary named Horselover Fat. The book itself is a hybrid, a melange of autobiography and fantasy that’s laced with an encyclopedic range of philosophical and religious information: citations from the I Ching, Henry Vaughan, Heraclitus, Wagner, Xenophanes, the Bible, Pascal, and, of course, the science-fiction writer Philip K. Dick.

The first half of the narrative is a loosely autobiographical account of Dick’s/Fat’s own “pink light” experiences of 2-3-74. Then Fat and his friends go to see a trashy B-movie called Valis. Like kabbalistic scholars or acidheads who see meaning everywhere they turn, Fat and his friends uncover a host of subtle symbols and puns in the flick, all of which seem to refer to Fat’s half-baked theophany. Here Dick the author implies that the divine virus can infect you through the process of reading and decoding the cultural hieroglyphs scattered about the world. And since the film Valis clearly emerges from the same pulp ghetto that Dick himself wrote for throughout his mostly marginal career, he sly hints that careful readers of his own trashy paperbacks, with their lurid covers and cheesy titles, may pick up far more than they bargained for.

Dick spent his last years in Orange County, living only a few miles from Disneyland. For a writer obsessed with the metaphysical tango between the authentic and the artificial, the environment was almost too perfect. Ambiguously characterizing the theme park as an “evolving organism,” Dick tied its synthetic realities to both the global developments of postindustrial culture and to the ersatz constructs of his own books. As he pointed out in his late essay “How to Build a Universe that Doesn’t Fall Apart in Two Days,”

…today we live in a society in which spurious realities are manufactured by the media, by governments, by big corporations, by religious groups, political groups…unceasingly we are bombarded with pseudo-realities manufactured by very sophisticated people using very sophisticated electronic mechanisms. I do not distrust their motives; I distrust their power.

As Jean Baudrillard has argued into the ground, simulation rather than representation has become the defining characteristic of cultural signs and artifacts in our time. For Baudrillard, the objects of simulation transcends the binary opposition of “authentic” and “fake,” “original” and “copy.” The technological simulacrum creates its own reality, which Baudrillard calls the “hyperreal,” a kind of ersatz parody of Plato’s ideal world of forms. For example, when you download a printer driver from the Internet or record a CD onto digital tape, you do not “copy” the information so much as replicate a hyperreal object.

For Baudrillard, the power of simulation only further extends the reach of what Guy Debord castigated in the 1960s as “the society of the spectacle.” The media have become a kind of orbiting genetic code that “mutates” the real into the hyperreal, thereby producing “social control by anticipation, simulation and programming.” Like Dick, Baudrillard saw Disneyland as the archetypal hyperreal environment, though perhaps the technophilic “Gulf War” we watched through the dark glass of CNN, with its smart bombs and virtual-reality pilot runs, should stand as the most delirious thrill ride yet offered by the new world order of simulation.

As an exhausted rationalist, Baudrillard simply abandoned himself to a morbid celebration of the pixel apocalypse, giving up any notion of resistance or transformation while ignoring the messy realities that gum up the works of all such grand intellectual scenarios. But Dick never gave up his commitment to the “authentically human,” the “viable, elastic organism which can bounce back, absorb, and deal with the new.” He also recognized that simulacra lie deep in our souls, and that we are not so far from the spiritual paradigms of the ancient world, with their camouflage spirits, talking images, and automata gods. And so Dick redeployed the gnostic struggle for authenticity and freedom within the hard-sell universe of simulation. The world is a prison not because of its materiality — which was the opinion of some of the ancient “Gnostics” — but because of the hidden orders of power and control it houses: the various corporate, political, and ideological archons herding us into increasingly compelling synthetic worlds.

Dick’s greatest novel of demiurgic media control is 1964’s The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch. In order to escape the dismal toil of their lives, the colonists on Mars resort to Perky Pat Layouts, miniature doll-houses complete with Pat and Walt, svelte figurines resembling those postwar archetypes Barbie and Ken. After gathering together in their hovels, the colonists swallow an illegal drug, Can-D, which “translates” them into Pat and Walt’s Baywatch-like lives for a painfully brief spell. Some colonists view their virtual trip as escapism, others as a religious experience in which they lose the flesh and “put on imperishable bodies” instead. A satellite owned by Perky Pat Layouts orbits Mars, emitting a stream of ads for new Perky Pat accessories, while the DJs deal Can-D on the side. Even psychic powers are exploited for commercial gain, as “pre-cogs” working for PPL use their gifts to predict which new accessories will be hits with the colonists.

As Peter Fitting points out, Three Stigmata paints a world where “the liberatory potential of the media and new technologies has been completely debased.” We are not so far from this world. Increasingly Hollywood churns out, not films, but events: virtual constructs that envelope us like theme park rides and which seep into ordinary life through spin-offs and a tsunami of merchandise. Much of children’s television fuses toys and imaginative experience; kids (and their parents) must buy their way into these worlds in order to “play.” Though distributed media like the Internet hold out the possibility of democratizing the imagination, high-tech simulation is expensive, and crude corporate-run virtual realities have started popping up on the World Wide Web like the mushrooms of Wonderland.

But things get much worse for the hapless characters in Three Stigmata. The industrialist Palmer Eldritch returns from the Proxima system with Chew-Z, a new and stronger drug that competes against Can-D with the slogan “GOD PROMISES ETERNAL LIFE. WE CAN DELIVER IT.” Chew-Z needs no Layouts to work, but it also possesses the distinctly negative indication of putting the user into a universe which Eldritch controls, a universe that is difficult, if not impossible, to escape from. Dick paints Eldritch as a nefarious and possibly alien figure, his “three stigmata” (a prosthetic arm, eyes, and teeth) symbolizing what Dick saw as the “negative trinity of alienation, blurred reality, and despair” we all risk by losing our capacity for empathy and by giving into the technology of control.

Like the Gnostics of old, Dick flip-flopped between viewing the demiurge and his archons as evil, or as aberrant and selfish products of their own ignorance and power. The difference is crucial: the Manichaean notion that good and evil are absolute principles sucks you into a harsh and rather paranoid dualism, while the other, more “Valentinian” mode of gnosis opens into a continual transformation, an awakening that’s always on the fly. For the Valentinians of Alexandria, the moment of transcendence is not a E-ticket out of here but a signal fed back into the maze of the churning world. As Leo Bulero, the hero of Three Stigmata, writes with quiet hope, “I mean, after all; you have to consider we’re only made out of dust…So I personally have faith that even in this lousy situation we’re faced with we can make it.”

The distant alien god of the Gnostics may be nothing more than a metaphysical rumor lurking in the back of metaphysical bookstores, but the false god they called the demiurge is alive and well and living in technoculture. Networked computer games, Hollywood special effects, and virtual theme park rides all seek, not only to just distract or entertain, but to immerse us into new, concocted realities. In Out of Control, Kevin Kelly discusses “God games” like Populus and SimEarth, which allow players to play demiurge, tweaking creation by altering levels of carbon dioxide or the rate of urban development. Kelly points out that these games parallel the science of artificial life, where researchers “grow” synthetic life-like forms by introducing basic rules of behavior and then letting whole worlds of code evolve inside the computer. “I can’t imagine anything more addictive than being a god,” he writes. “A hundred years from now nothing will keep us away from artificial cosmos cartridges we can purchase and [then] pop…into a world machine [in order] to watch creatures come alive and interact on their own accord.”

Of course, novelists have been creating spurious worlds for centuries, and before them bards and shamans. Much SF writing — especially that “hard” SF that aspires to the rigor of “hard” sciences — works by establishing a set of axiomatic “What If?” assumptions, and then “running” an internally-consistent narrative based on those parameters. As Dick writes in his “How to Build a Universe” essay, “it is an astonishing power: that of creating whole universes, universes of the mind. I ought to know. I do the same thing.”

But Dick yanked the rug out from under the technocultural mania for producing ever more vivid and life-like simulations. “I will reveal a secret to you,” he writes in the same essay. “I like to build universes that do fall apart. I like to see them come unglued, and I like to see how the characters in the novels cope with this problem.” As a creator of worlds, Dick was not a proud and all-controlling demiurge but an ironic Trickster, a Shiva with a “secret love of chaos.”

But how does chaos and disorder fit into Dick’s various information cosmologies? Like Thomas Pynchon, Dick was obsessed with the second law of thermodynamics, and he coined words like kipple and gubble to denotes the corrosive power of entropy and its ability to render form into formlessness. Along with Norbert Wiener, Dick viewed entropy metaphysically, casting it in some tales as evil incarnate or as the sign of some cosmic Fall. In contrast to this, Dick later came to laud the positive and “negentropic” (or anti-entropic) power of VALIS’s restorative information. This makes good human sense: as finite, far-from-equilibrium organisms, we are whirlpools of order and information whipped together for a time against the steady downstream drift of entropy.

However, the pseudo-realities forged by the archons play havoc with this Manichaen scheme. In a world of manufactured illusions, the gremlins of entropy — malfunctions, interference, decay — can paradoxically liberate us by gouging holes in the smooth surface of simulation; these corrosive gaps create the space for breakthroughs and insights, imaginative or real. In a number of Dick’s works, it is only the anomalous decay of objects that alerts the characters that the false world around them is not what it seems. Even the disguised God of VALIS appears as “trash discarded, debris no longer needed.” In a sense, entropy is what kills all our illusions, and this dark liberation becomes even more important in a world of potentially insidious, or at least overbearing, technological constructs. As public spaces devolve into theme parks or malls, where the creative force of organic life is managed down to every blade of grass, entropy — mildew, rot, mulch — even becomes the final sign of nature and its spontaneous freedom.

In The Divine Invasion, a late Dick novel that carries on many of VALIS‘ metaphysical themes, electromagnetic noise play a liberating role. From his private dome on the off-world colony CY30-CY30B, Herb Asher transmits information and music to the other colonist domes. His high-tech entertainment system continually plays videos and tapes of his favorite pop singer Linda Fox, whose holographic posters cover the wall. But he keeps picking up a soupy muzak version of Fiddler on the Roof. Asher later discovers that he is actually in cryonic suspension, where his inert body picks up signals from a nearby radio station broadcasting the Broadway musical. Like the spirits in Swedenborg’s afterworld, whose first order of business is to convince incoming souls that they are actually dead, the radio interference acts as an Intercessor, calling Asher to wake up to his actual condition.

By insisting on the liberating truths concealed in crossed-wires and mixed messages, Dick serves as a kind of spiritual godfather for media tricksters everywhere, from graffiti artists to video activists to hackers to hoaxers. In his prescient 1972 speech “The Android and the Human,” Dick spoke glowingly about young phone phreaks like Captain Crunch, who built a blue-box that allowed him to make long distance calls for free. Anticipating the more frazzled edge of online libertarianism and the ethical ambiguities of hacker pranks and poachings, Dick went on to claim that in “a totalitarian society in which the state apparatus is all-powerful, the ethics most important for the survival of the true, human individual would be: Cheat, lie, evade, fake it, be elsewhere, forge documents, build improved electronic gadgets in your garage that’ll outwit the gadgets used by the authorities.”

Dick was no futurist; his value as an SF writer lies not in any predictions about the specific technological course of human civilization (there are few computers in his work), but in his extraordinary intuition for the subjective conditions of the mutating human self. So if Dick’s counter-cultural battle-cry sounds somewhat dated in an era when criminal cartels, fascist militiamen, and transnational corporations wage similar tactics against the state, his spiritual commitment to freedom does not. We cannot know whether the virtual webwork now girding the earth will become a holistic society of mind or a playground for the archons, a “vast active living intelligence system” or an infinite nest of Perky Pat Layouts — and the likelihood that it will fuse all of these possibilities, while producing enough novelties and shocks to surprise all but the most committed paranoids, only begs the question. Which is simply this: What are the ethical “postulates” that guide the self through such a world?

For Dick, one of these fundamental values was simply compassion, the caritas of St. Paul, or the empathy of Lord Running Clam, the telepathic Ganymedean slime-mold in his Clans of the Alphane Moon. We feel compassion for and in his characters, ordinary flawed people struggling with impossible emotional and ethical contradictions; we recognize these people and their slapstick dystopias; they are us. And yet Dick’s point of view was extremely alienated and critical; questioning authority (even the authority of the author), he shifted like an ontological nomad between subjects and truths and positions of power, constantly testing for the trap doors in the theater of the world. His was not a gnosis that knows, but one that seeks to know, or rather dissolves its own convictions into the anxious mysterium. Dick loved the seventeenth century English religious poet Henry Vaughan, and I think he may have seen himself in the final lines of Vaughan’s “Man”:

Man is the shuttle, to whose winding quest

And passage through these looms

God ordered motion, but ordained no rest.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription, though for now I will not be offering any subscriber-only content. ou can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

This is hilarious. And depressing! It reminds me of a point I made last year: that while "AI is Weird," that weirdness is always in a complex relationship with the banal. Weird and Banal are the new polarity!

Great summation of his theology and ethics.