The New Yorkers are everywhere. Stacked on the nightstand, frosting the john, piled on the kitchen table next to the battery recharger and the bougie electric kettle. And they just keep coming, ticking off the quickening weeks, worming their way into the narrow spaciotemporal cracks in my day. And they’ve been doing so, in various places of residence, for most of my life. This despite the fact that the humor writing remains unfunny, the short stories bloodless (my fav was by Stephen King from like twenty years ago), and the Manhattan posturing smug and parochial, just like Saul Steinberg’s famous “View of the World from 9th Avenue” cover, only not so cute.

I occasionally threaten to cancel the subscription — a move that Jennifer resists because of, yes, the cartoons. But most issues have at least a couple good things in them, and the writing and research is reliably non-insulting to the intelligence. I have enjoyed the rise of newer voices, like Jia Tolentino and Hua Hsu, and appreciate growing grizzled alongside OG staff writers like Alex Ross, Peter Schjeldahl, Anthony Lane, and Louis Menand. And I really admire the commitment to a copy-editing style, an art that these days seems to have been handed over entirely to machines, or the void.

Except those aren’t the only reasons I keep it coming.

As a writer with more ambition and envy that is good for me, I need the New Yorker to drive a double-pincer movement, a love-hate wrangle with Consensus Status bound up with two facts. One is that, for all its mockable flaws, and even its mockable achievements, the New Yorker still Stands For Something. It is a premium publication that maintains the fantasy of a “smart set” holding down the acme of taste and sensibility. The magazine is like an upper-middle-brow Asgaard where the gods hobnob as trolls and giants hammer away at the foundations, inflicting a Götterdämmerung of social media, gatekeeper meltdown, and an algorithmic race to the bottom.

The second fact is that I never got through those rainbow gates, and almost certainly never will.

As a young freelance writer and critic in New York in the early ‘90s, I worked myself into the lower ranks of the slick magazine world, writing about drugs and bands and weird technologies. Given my pop intellectual goals and my dedication to good writing, the New Yorker became the ultimate object of aspiration. I gave it some hustle, but I’ve never been good at networking. Even my Yalie friend who worked at the magazine told me to give up because the editorial department was “too straight.” Cold comfort. At least my commitment to the weirdo fringe, a nomad zone which provided me a sense of independent identity as well as a source of curveball pitches, also helped justify my frustrated ambition. To extend the Wagner analogy, I felt like a Loge who could hang with the gods if he wanted to but preferred to hunt his magic elsewhere. But I was equally an Alberich, who enviously chose to shine in the underground rather than serve, or schmooze, in heaven.

(Full disclosure: I actually did make it into the pages of the New Yorker, when Adam Gopnik cited the “Dick scholar Erik Davis” in a 2003 piece on the Matrix films. My friends had fun with that one.)

Burning Shore is the latest chapter in my post-NYC writing “careen.” I turned to Substack out of the gut sense that, in the current environment, it offers a creative, dynamic, and pleasantly old-schoolish solution to the problem of writing stuff I want to online and getting paid for it. (As a Gutenberg soul, I still prefer writing for books and print.) But while Substack opens up many possibilities, one thing it does not and cannot dangle is anything like the brass ring — not gold, it’s important to remember — of Consensus Status.

So you can imagine I had some feelings when I opened the Jan. 4 & 11 issue of the New Yorker and saw “You’ve Got Mail,” a piece on the “newsletter service” Substack. The author: Anna Wiener, a smart and incisive thirtysomething ex-New Yorker whose appropriately caustic and excellently entitled 2020 Silicon Valley memoir Uncanny Valley helped land a choice gig as tech critic at the mag.

I put off reading “You’ve Got Mail” for a couple weeks, because I knew it would rile me up. I also knew it would lead with a story about some writer much younger than me, whose quirky Substack pub, which I would duly check out and find chatty and alienating, was racking up vast numbers of adoring fans and raking in piles of cash, a kind of success that, alongside Wiener’s enviable if still nebulous parvenu aura, provided exact figures with which to measure myself and find myself wanting. I was right on both counts. But the real irks were elsewhere.

They came from both sides, proponents and critics. Having spent an isolating day at a Zoom conference for Substack writers, filled with millennial talk of analytics, social media integration, and hamster-wheel fan interaction that had nothing to do with actual writing, I was under no illusions about feeling particularly at home in the Substack “community.” But I was not quite ready for CEO Chris Best’s statement to the New Yorker that the company’s goal is to “make it so that you could type into this box, and if the things you type are good, you’re going to get rich.”

Talk about rich! This statement has it all. There is the reduction of writing to a mechanical act of bare life — “typing” — that itself is submitted to an enframing technical form — the online textfield, or box. Then there is the nihilistic, post-literary collapse of value — the “good” — to the universal equivalent of money. If it sells, its good. And finally there is a lure and a lie, or at the very least an exaggeration. No way is everyone slinging good stuff on the platform getting rich.

On the other hand, Wiener gives voice to some fatuous critiques of the platform, which equally sacrifice any discussion of quality, meaning, or actual writing to a concern for political economy that sounds smarter than it is. My favorite quotation in this category comes from the media historian and NYU professor Lisa Gitelman. She pushes back against what Substack would claim as its “democratizing” gesture, redescribing it as “the democracy of neoliberal self-empowerment. The message to users is that you can empower yourself by creating.”

Don’t get me started about the workings of Ms. Gitlman’s own rival platform, the contemporary academy. (From my perspective, scholarship has its uses and values, but it is also an infernal engine of personal disempowerment, toxic political messaging, and absolutely terrible writing.) Instead, let’s think through Gitelman’s last line. She seems to be saying that enjoying the sense of power and satisfaction that comes from creating something yourself — recording a song, knocking together a bookshelf, inventing a new dish, scribbling a poem you actually like — is simply a capitulation to neoliberal ideology. Or maybe she is saying that this creativity, or “labor” if you want, only becomes neoliberal if you use a platform to distribute it and try and earn some coin. By this logic, Etsy is also a regressive expression of neoliberal self-empowerment, so maybe we should just be honest about the situation and shop at Amazon after all.

Wiener’s own pull-quote conclusion is that “Substack is a natural fit for the influencer, the pundit, the personality, and the political contrarian.” These may not be terrible things exactly, but they’re not “good,” at least from the New Yorker’s embattled position as a bastion of liberal Consensus Status holding the line against the Götterdämmerung hordes. The inclusion of “personality” is, again, a bit rich. As anyone who reads the New Yorker online knows, the magazine now identifies their staff contributors with cutesy but sober cartoons.

I don’t identify with any of the categories on Wiener’s list, and I am not alone. Absent are freelance writers or poets or scholars or cult authors, the sort of scribblers whose recherché topics, intellectual sensibility, or peculiar style naturally precludes virality while nonetheless attracting a passionate if eccentric core audience. I’ve long thought of myself as a cult author, looking for ways to share, or get away with, my weirdo-smart explorations as I pass through various publishing ecologies: alt weeklies, magazines, books, blogs, academia, and now Substack. I guess I was just pumping my personal brand all along.

Events

— SF PSYCHEDELIC SANGHA: After a month off, I will be reconvening the monthly online gathering of the San Francisco Psychedelic Sangha at 6pm PT on Saturday, February 6. The event will combine a talk, a practice, and discussion, all focused on the heretical arts of the dharmanaut. The emphasis is not about taking psychedelics, or even navigating psychedelic experience, so much as understanding yourself and the world through a psychedelic lens. Tonight we will be honing in on the meaning of attention both inside and outside of meditation and visionary experience. Sign up here; any dana should be tossed into the SF Dharma Collective bucket.

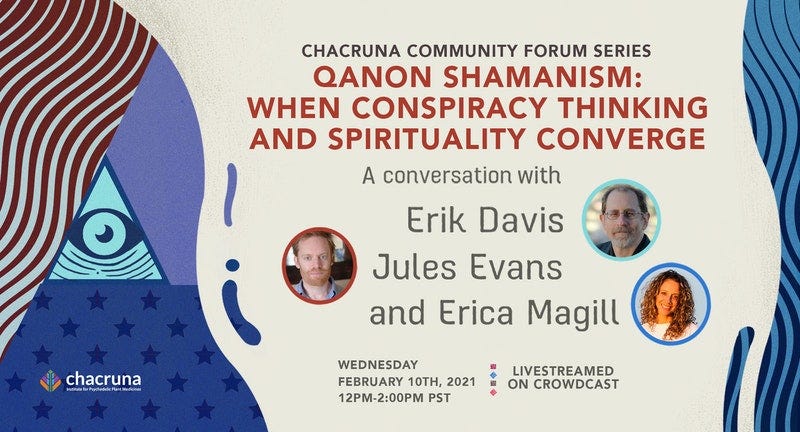

— CHACRUNA COMMUNITY FORM. You might be tired of hearing me go on about Jake Angeli, the QAnon Shaman, but we are not done with the reckoning and its implications for transformative culture. (As you will see from some of my links below.) Over the last year plus, scores of “spiritual but not religious” communities — engaged in wellness, yoga, mindfulness, and psychedelic healing — have seen the virulent spread of paranoid plots, baseless vaccine conspiracies, and feverish rumors of Satanic mind-control. Yes, we should interrogate mainstream narratives, but what else is going on here?

The next Chacruna Community Forum, which takes place Wednesday, February 10, at noon PT, will be devoted to “QAnon Shamanism: When Conspiracy Thinking and Spirituality Converge.” I will be in conversation with Jules Evans, who authored some widely-read pieces on “conspirituality”, and Erica Magill, one half of the dynamic duo who runs the Lost Angels Yoga Club and the remarkable mailing list LAYC Almanac. Together we will explore this worrying trend and map some exit ramps from the rabbit hole. Register here.

Appearances

— MAGIC AND ECOLOGY. Animism is not fairy-tale dust bunny to me, but a philosophically and aesthetically valid framework for engaging the world, including the technological world. As such, I was incredibly honored to be interviewed by Simone Kotva for the fascinating Magic and Ecology project, an online symposium, podcast, and art exhibit that explores the myriad linkages between esoteric perception, political possibilities, and ecological thinking. (Other interviewees for the project include folks like Isabelle Stengers, David Abram and the witch and artist Charlotte Rodgers.) Here I was able to think big, and weave together themes from Techgnosis, High Weirdness, and the mostly unpublished work I’ve done on contemporary animism.

— A GLITCH IN THE MATRIX. Last Saturday, I hopped over to Sundance to see Rodney Ascher’s new documentary A Glitch in the Matrix and participate in a short Q&A panel for the film. The movie, which has just opened for general release, explores the simulation hypothesis, the probabalistic cyberpunk reboot of the ancient intuition that life is a dream. Ascher traces the idea that we live in a CG sim through PKD’s Valis experiences, the Matrix movies, video games, and the philosophical arguments of Nick Bostrom, who appears as a somehow spooky talking head. Cartoonist Chris Ware and writer Emily Pothast also dropped some incisive words; I got to weigh in as well, and I am happy with both my comments and my facial hair.

But we were just the support crew. Ascher centers his story on “eyewitnesses”: individuals, some of whom admit they may be suffering from mental illness, who experience the ordinary world as a simulation, with glitches and NPCs and too-perfect synchronicities. In one case, which is already garnering Ascher some grief, the headspace goes most foul, as we hear Joshua Cooke, who murdered his parents and later presented the “Matrix defense” in court, narrate his deluded deeds. (In the end Cooke abandoned the defense and willingly went to prison.) Brilliantly, Ascher and his team rendered the eyewitnesses — though not Cooke — as goofy CG avatars.

As I noted in a recent post, Ascher’s films are all great, so I expected to like Glitch a good deal. But it’s more accurate to say I was blown away. As one correspondent put it, the film was invigorating, both conceptually and aesthetically, as the sound design, music, and copious digital graphics combine into a confrontation with a dread conundrum whose cultural significance is more pervasive than many critics of the film recognize. Before the panel, I told Rodney that Glitch was a proper mindfuck, which he accepted, rightly, as the highest of complements. The panel was fun — I “did” Sundance for a full half hour. I chose not to attend the VR avatar schmooze room later that weekend, though. I am worn down by screen socializing these days, and besides, with Glitch still on my mind, it seemed a little darkly ironic even for me.

— REBEL WISDOM DOCS. The Rebel Wisdom boys knocked on my door twice last month. I’ve written a few pieces on psychedelic capitalism over the years, and given some talks on the topic as well , so when Alex Beiner was putting together a short documentary on “The Rise of Psychedelic Capitalism,” he gave me a buzz. The doc features a solid range of perspectives, and includes valuable comments from Usona Institute’s Bill Linton, incisive critic Jamie Wheal, and Kat Conour, co-founder of the North Star Project, which is attempting to ethically wrangle the emerging industry. There is a lot of drama around this topic these days — finger-pointing, hand-waving, rabbits out of hats, it’s a real show. At this point I don’t know what more to say: commercialization is happening, it might outrun business as usual, but probably not. Let’s hope that open science, just access, and patient-centered care can decelerate what Wheal sees as an inevitable “race to the bottom.”

“The Rise of Psychedelic Capitalism” first streamed on January 7, a day after an even stranger mutation of psychedelia erupted onto our screens straight from the United States Capital. I used Burning Shore to write a bit about Jake Angeli, the now legendary QAnon Shaman, and soon David Fuller, the other Rebel Wisdom rebel, drew me into a conversation. The finished piece includes great stuff from my old esoterica colleague Gary Lachman, and my newer conspirituality critic colleague Jules Evans. And yes: I would love to stop talking about this stuff, but I am afraid that critical weirdos possess relevant angles on this frightening rent in the body politic.

— LIFE IS A FESTIVAL. I have always enjoyed undergroundy festivals: Deadshow parking lots, Rainbow Gatherings, Burning Man, Boom. Even when the scene is goofy and the music meh and the dust dusty, I still enjoy melting my psychic armor into the neotribal flux of stoned bonhomie, humorous grooves, and serendipity. I miss that feeling terribly. These days I imagine I could achieve ecstatic collective bliss at a conference of dental technicians in Peoria.

Eamon Armstrong hosts the podcast Life is a Festival, which is devoted to the proposition that festivals offer serious models for inhabiting the “default world” in better ways than we usually do. Armstrong is more of a canny hedonic engineer than a warrior of psychedelic wu — he is grounded and intelligent, and bravely foregrounds human vulnerability, both his own and his guests’. Our 2020 talk on weirdness (episode #23, folks) went in pleasantly unexpected directions.

Last month, Eamon and I spoke again, and for the same conspiritual reasons that have brought other folks a’ knocking of late. It was a good one. As is his wont, Armstrong steered me to reflect on my own sense of responsibility, and even complicity, as a translator of esoteric weirdness at a time when the tides of “metaphysical mud” is rising. At the same time, we also discussed our own susceptibility to conspiracy thinking and the necessity to embrace practices of “withering self-observation.” If life is a festival, it’s not only about group ecstasies, but also about adjusting to the provisional and ephemeral mess of it all.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Hi Eric,

I finally subscribed to your Substack after reading Chris Best's quote and your reaction to it (a longtime TechGnosis and High Weirdness fan). It truly has it all :)