Russ House & Gardens

The Burning Shore, no. 7

My middle name is Russ, which is also my father’s given name, his middle name being my own Erik. There are no family reasons given for this loop-de-loop, nor for the Erik, nor for why the Nordic spelling was chosen over the more common German one. Whatever the cause, I praise all Æsir and Vanir for the K, which not only balances the easy “E” with a Krazy Kat bookend, but lends my otherwise ordinary name a slight google hedge against all manner of Eric D.’s: outfielders, clowns, rugby players, and most excellent cornerbacks.

The cornerback in question, it should be mentioned, played for the 49ers. This fact is relevant, or at least resonant, because of the story I want to tell here, which unrolls from the other name I share with my dad. Russ is not short for Russell, you see, but is a kind of patronym drawn from my great-great-great grandfather Emmanuel Charles Christian Russ, who put ashore at the newly rechristened hamlet of San Francisco, with brood in tow, in the timely year of 1847. He wasn’t a 49er, then, but a pre-49er: an avant-Argonaut.

I grew up thinking that the Russ family was German, which, along with my mother’s ancestry, would make my DNA more über alles than anything. But though I.C.C. (as we called him) was born in Hildberghausen, the royal seat of a small and heavily taxed duchy in Thuringia, his family had either fled or gotten kicked out of Poland after the Russians grabbed their doormat back in 1791. In my files I have a photograph of a portrait of the purported Polish ancestor, identified in pen on the back of the picture as “Count Rienskei (sp?).” I see a slightly amused fellow with a sharp ’stache, though to my eyes his uniform looks more like an Ohio State drum major than a Polish aristocrat.

Who is this guy anyway? Is his phenotype echoing in mine? Can I see my father’s eyes in his? Is he actually a nobleman, and why do I care? Such questions haunt ancestral work, which flickers between phantasm and dull data, projection and resemblance, lore and lies. As you piece together your fragile tissue of tales, persons, and relations, it becomes clear that this pattern takes shape against oblivion, which grows more intimate at the same time, nibbling at the edge of every research breakthrough and connection. The abyss is close to home, as the Mekons sang.

I.C.C. was a silversmith by trade, but he also fashioned fireworks for the local duke. Ka-BOOM—my imagination crackles at this hand-me-down bit of lore. But the flash fades fast. When the Saxe-Hildburghausen duchy was more or less dissolved in 1826, I.C.C. lost the gig and, according to my distant cousin Jane Bernasconi, had trouble supporting the growing family with his regular trade. Or maybe he just got bored.

In any case, I.C.C. emigrated alone to New York City in the early 1830s. He sold enough jewelry and watches to send for his wife and family and set up a storefront in New Jersey. By 1845, the family had a decent pile, and everyone was probably feeling good and cheery when, on June 24 of that year, the whole family ferried over to the city to witness the massive funeral procession for President Andrew Jackson. They returned from the spectacle to find their store burglarized, and everything of value gone. Soon the clan, now numbering almost a dozen, were encamped in the tenements of East New York.

It almost serves them right. Andrew Jackson was a monster, an ardent slave-holder and anti-abolitionist who unleashed the Trail of Tears and other horrifying rip-offs on the native peoples he called—get this—“my red children.” But the Russ family’s rapid plunge in circumstances also generated the momentum that allowed them to catch and ride the wave of western expansion that Jackson had put into motion. The United States was at war with Mexico in 1845, and, in an underhanded and aggressive move that was condemned as such by anti-imperialists of the day, President Polk ordered Colonel Jonathan Stevenson to gather a regiment of New York volunteers and to sail around the Horn to fight Mexico on what was then Mexican soil: Alta California.

The goal of this operation was crisply captured by the title of Donald Biggs’ book about Stevenson’s Regiment: Conquer and Colonize. The U.S. needed soldiers out west to push back Mexico, but they also needed settlers. As such, a variety of professionals and “persons of good habits” were recruited, including I.C.C. and his eldest son, while two of the younger Russ boys were tasked with fife and drum. (My great-great-grandfather Henry was only seven at the time.) So while the large bulk of Stevenson’s Regiment was composed of single men, the whole Russ family shipped out in the fall of 1846 on the Loo Choo, a 639-ton merchant ship built in Medford, one of four ships that transported the regiment to the west coast. As Biggs dryly notes, these vessels were packed, not with warmongers, but with “immigrant adventurers bound for a distant land of many charms under the protection of government.”

I want to write more about the voyage of the Loo Choo, about the four days of sea-sickness the wayfarers faced the moment they left New York; about Major Hardie’s assessment of the men’s discipline (“Not Good”) and military appearance (“indifferent”); about the weeks of monster seas off Tierra del Fuego; about the barrel of sauerkraut that mother Christina insisted they bring along for the ride; and about the wheezing burst of “Yankee Doodle Dandy” that greeted the ship when, in March 1847, it passed by the old presidio of San Francisco, which during the six months the Loo Choo had been at sea had been seized by the Americans, obviating the need for the volunteers to actually fight anybody. But I think it’s more important to consider that “under the protection of government” thing instead.

The free ride the Russ family got recalls one of the central arguments that Joan Didion makes in her 2003 essay collection Where I Was From, a book that beautifully and bitterly deflates the California myths Didion supped on growing up in Sacramento to an old pioneer family. A mea culpa that excoriates whatever shreds of nostalgia and romance lurked in her earlier work and attitudes, Where I Was From is a valuable book for us out here on the burning shore. Like most places, California’s major narratives are riven with lies, hypocrisies, violent undercurrents, and bleak ironies, and the whole Endless Summer branding demands, at least for many writers, an even more bleak realism in response—though nihilism and dystopia too, it needs remembering, are zones of California’s apocalyptic Dreamtime.

I love Didion’s 1960s meditations on this cracked place almost as much as I love her prose. But I learned long ago—from reading her unforgiving take-down of the ex-Episcopal Bishop (and Phil Dick pal) James Pike in The White Album—not to expect too much of the weird California that compels me to pass muster in her eye. That’s OK; it’s a big place and there is room for all sorts of Californians, including ex-Californian, Upper East Side turn-coats like Didion. Kidding. Still I cannot repress the thought of another Californian, the delightfully shameless Eve Babitz, who, at the beginning of Eve’s Hollywood, thanks Didion and her husband John Dunne “for having to be who I am not.”

Where I Was From—note the past tense—roasts old pioneer myths that I was spared growing up, and attacks the Golden State as well for its prisons, its asylums, and its heartless corporate libertarianism. But Didion’s bleak air of grievance, her terrible disappointment with it all, also sours her critical disavowal; unmixed with love or fascination or even attachment, the debunking seems party to her own affective limbo, at which we can merely stare. Nonetheless, her central claim is absolutely key: California’s roster of independent, innovative, and risk-taking pioneers and innovators is a myth that radically distorts how much Californians have always depended on U.S. largess, public institutions, and strategic long-term development plans. And it hasn’t just been that way since the beginning. As I.C.C.’s experience shows, it’s been that way since before the beginning.

Still, pluck is pluck. Putting your family on a troop ship for six months and volunteering to wage war at the edge of nowhere takes some gumption—even if “gumption” is pioneer myth-speak for being at the right place in the right time with the right—or wrong—historical forces backing you up.

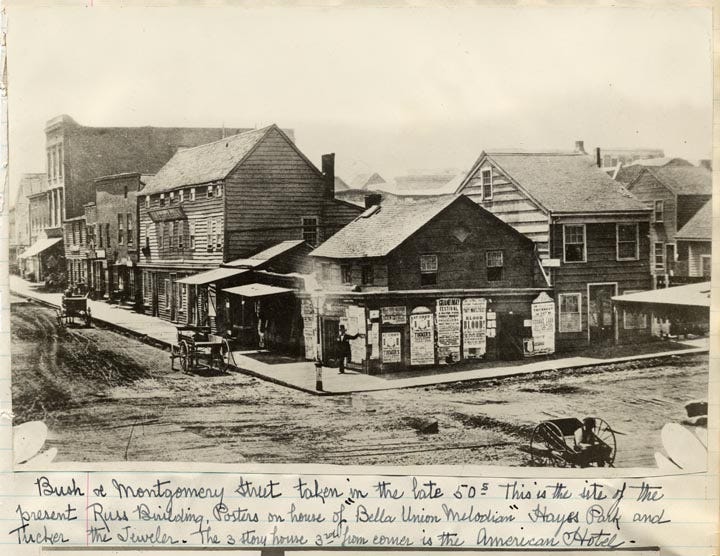

Arriving at a city of some 200-odd souls, I.C.C. bought three 5-vara lots south of the main hamlet, past the dunes down Montgomery street, which then fronted the bay. They purchased the lumber from their bunks on the Loo Choo and slammed together a ramshackle affair later reinforced with adobe. (That’s the Russ residence to the far left above, behind the trees, now the Montgomery block between Pine and Bush.) Then they built thirty-odd shanties, rented them, and bought more land. When gold fever hit, they were well situated to take their cut of the dream, as transients multiplied by the thousands, prices exploded, and I.C.C. turned his metal-working chops towards assaying and jewelry. “Take your poke to Chris Russ,” the miners said of I.C.C., who sometimes made rings out of the ore.

Living on Montgomery Street meant living in the heart of the action, which during the Gold Rush also meant thievery, brawls, whoring, dance-halls, mindless intoxication, general cacophony, and the other sorts of rowdy antics that thrive in far-flung port towns with loose cash and little law. Soon Russ moved his brood, including his four youngish daughters, into a large house out in the sticks. One of the many fires that beset early San Francisco—some of them set by the Sydney Ducks and other hooligan gangs to cover their crimes—had taken their Montgomery home anyway, and in its place they built the American Hotel, which is the humble three-story peaked structure standing three buildings left from the corner in the shot below. (If the identification of the hotel is accurate, though, the corner we see must be Montgomery and Pine, not Bush as claimed.) Today this is the site of the Russ Building, a neo-Gothic office tower that was once the tallest in the city, and that passed from family hands long ago.

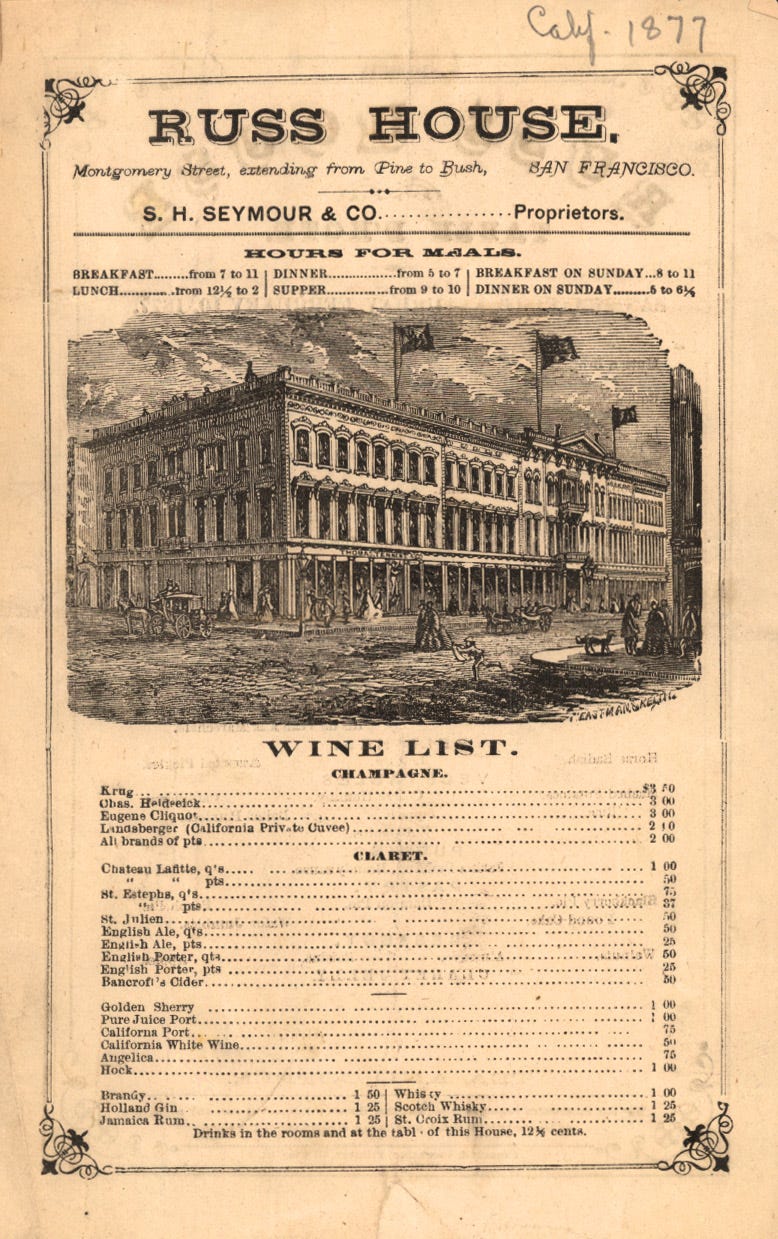

After I.C.C. died and the whole Montgomery block was acquired, the American Hotel was reborn as the Russ House, a massive three-story brick Italianate structure that served as the least pretentious of the city’s five big hotels. Ambrose Bierce lived there, and Mark Twain drank there. At $2 to $2.50 a night, rather than the $3 to $5 demanded by the Occidental or Lick, it was a deal. Forswearing the gilded mirrors and fancy French cuisine that drew the smart set elsewhere, the Russ House catered to traveling country folk, ranchers, farmers, merchants, and miners. “The furniture is substantial and plain, more adapted to use than ornament,” wrote one hotel reviewer in the Overland Monthly, “and apparently constructed with a view to its being able to resist the friction of boots as well as clothes.”

There is a demotic vibe that runs through the Russ tale that charms me, a frothing lager to go along with the filet mignon of I.C.C.’s business dealings and massive real estate holdings, for some time the largest in the city. This populist sentiment, which may be rooted in I.C.C.’s reportedly “jovial and friendly disposition,” manifested as well in the other large contribution that he made to the overblown young town: the pleasure resort he built in the huge and swampy South of Market plot where the family moved after fleeing the budding Barbary Coast.

Russ built his home on a dry knoll around 6th and Folsom, near the plank road that led out to the old Mission ruin. The frame of the house came from Boston, and the windows and sashes and apple trees—some of California’s first—were shipped all the way from the Old World. People liked to visit the grounds, at least if they didn’t get stuck in the mud. Seeing another opportunity, I.C.C. converted a chunk of his land into an entertainment park called the Russ Gardens. Here, for a fee, people whiled away their Sundays far from the dusty town. Immigrant communities—Germans, French, Irish, Scots—celebrated their national fetes, and everybody got to whoop it up for the 4th. But the ethnic ambience of the park was always clear. As Charles Caldwell Dobie sniffed in San Francisco: A Pageant, the Gardens “provided primitive entertainment and beer in the German fashion.”

All hail primitive entertainment! I found one nice description of a May Day blast that took place shortly after the gardens opened in 1853, when the Turner Gesang Verein, a German singing and acrobatics club, “leaped, balanced and twirled, danced, sang, drank, smoked and made merry.” On later occasions, the strongman Monsieur Guillot performed, as did the Great Blondin, who climbed a tight rope from the grass to the summit of the massive pavilion, pushing a wheelbarrow before him. According to the poet and travel writer Charles Warren Stoddard, there were few trees at the Gardens, and lots of painted scenes, making it resemble a toy Tyrolian village. “Meals were served at all hours, and beer at all minutes.” No word on any fireworks, but since San Francisco kept burning down, their absence makes sense.

Russ Gardens closed not long after I.C.C. died in 1857, giving way to more celebrated spots, like Woodward Gardens. Russ Street still runs for a few blocks nearby, but not many other concrete traces remain. I sometimes stroll down that namesake backstreet to Victoria Manola Draves Park, which the family donated to the city when their South of Market property was broken up. They called it Columbia Square back then, but its current name—honoring a local champ, the beautiful half-Filipina diver who won gold at the 1948 Olympics—is way more cool, and more fitting for a hood that Filipinos heavily settled in the early 20th century.

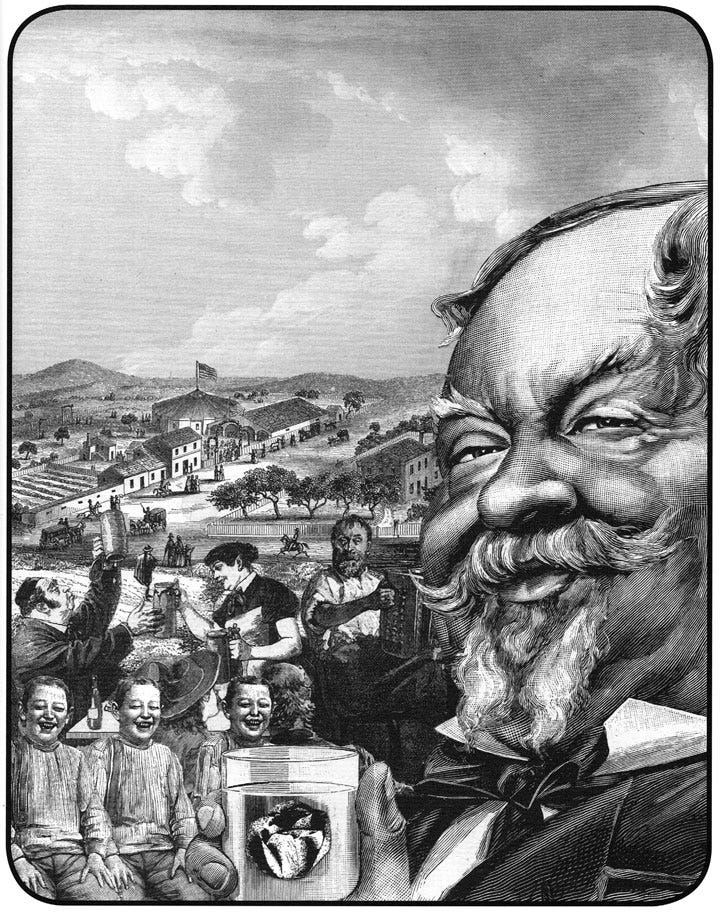

My favorite trace of the Gardens is a modern work of collage—an artform that, by the way, has inspired my own dense, sampledelic approach toward writing, history, religion—even reality. Wilfried Sätty was a German artist who moved to North Beach in the days of Beats and hippies. He constructed a cabinet of curiosities out of thrift store finds and magical street junk in his bohemian studio apartment, which he cheekily named “The North Beach U-Boat.” Practicing an explicitly alchemical art of juxtaposition and assemblage, Sätty produced psychedelic rock posters along with hundreds of dark, esoteric, and visionary collages, some of which were later used to illustrate Terence McKenna’s book The Archaic Revival. (A Sätty also illustrates the final chapter of my book High Weirdness.)

Sätty was into San Francisco history, and his extraordinary late work on that theme was gathered after his untimely death into the book Visions of Frisco: An Imaginative Depiction of San Francisco During the Gold Rush & The Barbary Coast Era. The image below celebrates Russ Gardens, and includes, in the center-left, part of an illustration of the actual place lifted from The Annals of San Francisco. That same publication, from 1853, also offered a numinous description of one celebration at the Gardens, a day when the weather was sweet, and the grounds “seemed beautiful beyond all expression of praise from the full heart that could only enjoy, while it knew not and cared not why.” That’s the kind of divine joy that sometimes sublimes even the most primitive of entertainments. It can transform swamp into heaven, beer into ambrosia, burghers into Bons Hommes. I have never seen an image of I.C.C., and the nose is all wrong, but this jovial fellow more than covers the absence.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of The Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. As a bonus you will get a paid-subscriber only audio recording of all new posts. And pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Dont forget me buddy.. you can send me something other than this website so we can remain private.