Thar She Blows

News and Notes

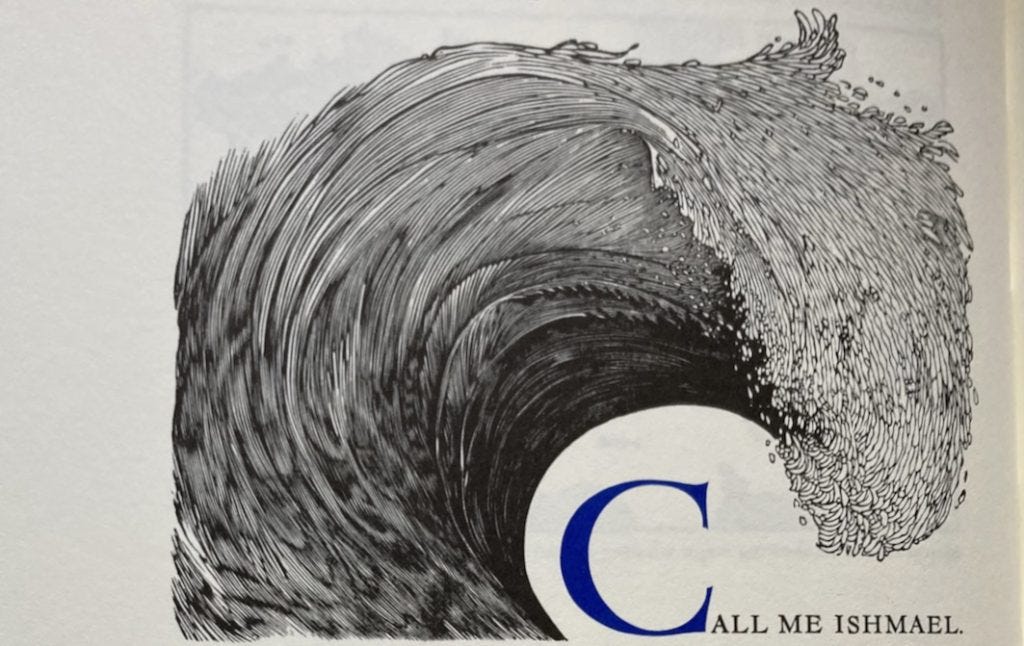

This has been my third time through Moby Dick, a novel I first read in my late teens, and years later in the apocalyptic fall after 9/11. I’m rereading it for an upcoming online seminar on the book I am co-teaching with JF Martel over at the Weirdosphere. The class starts this coming Tuesday, and if you hear the call of the wild and want to venture with us into the craziest and most prophetic book of the American canon, please consider hopping onboard. For six weeks, we will meet twice weekly, for talks and discussion. For more info, check out this link, which also gives Burning Shore readers a 10% discount.

Moby Dick is a lot of things. A lot of words, for one thing — a seething, sometimes overwhelming torrent of languages: scientific, mystical, goofy, poetic, morbid, mad. These multiple tongues enrich this book immeasurably, but can make the project of reading the thing feel rather intimidating. While we think its best just to go for it, we also invite folks to read in ways that work for them. Listen to some of it on an audiobook (we prefer Frank Muller), skim the “boring chapters” (which don’t really exist), and, at a minimum, closely read the specific chapters JF and I are going to concentrate on each week. Our aim is not so much to provide our own weirding takes on the Whale — which we will do, of course — but to support folks in settling into a fine and tasty meal with this justified classic, and its gnarly, playful, and unquestionably psychoactive prose.

A word about reading “classics.” There have always been classics, certainly centuries before bearded white males schemed to install themselves as arbiters of everything. The I Ching means the “Classic of Changes” — an oracular book for the eons, even if those eons keep not settling down. But what about actually reading the things? Is it worth your precious time to read The Whale, or Homer, or War and Peace?

My Mom has long pegged War and Peace her favorite novel, so three years ago I picked up a copy and said, fuck it let’s go. It was no more challenging than watching twenty seasons of excellent prestige TV. In fact it was an utter delight, just challenging enough to require me to minimize distractions, focus my weakening powers of attention, and get truly absorbed. Since then, I have always had one fat classic bubbling on the burner — Dostoevsky, Mann, Woolf, Musil, Kazantzakis. Say what you want about the concept of a literary classic, and the purported virtue, or not, of taking the time to read them. As a practice I have found it to be grounding, nourishing, illuminating, and, somewhat to my surprise, very entertaining — often far more entertaining than reading accessible contemporary fiction, genre or ortherwise. There is good new stuff out there, calm down everyone, but there is nothing like the chewy, resonating, and demanding claims of The Good Shit. And there is no richer, more glorious, and more fecund, fungi-festooned pile than Moby Dick.

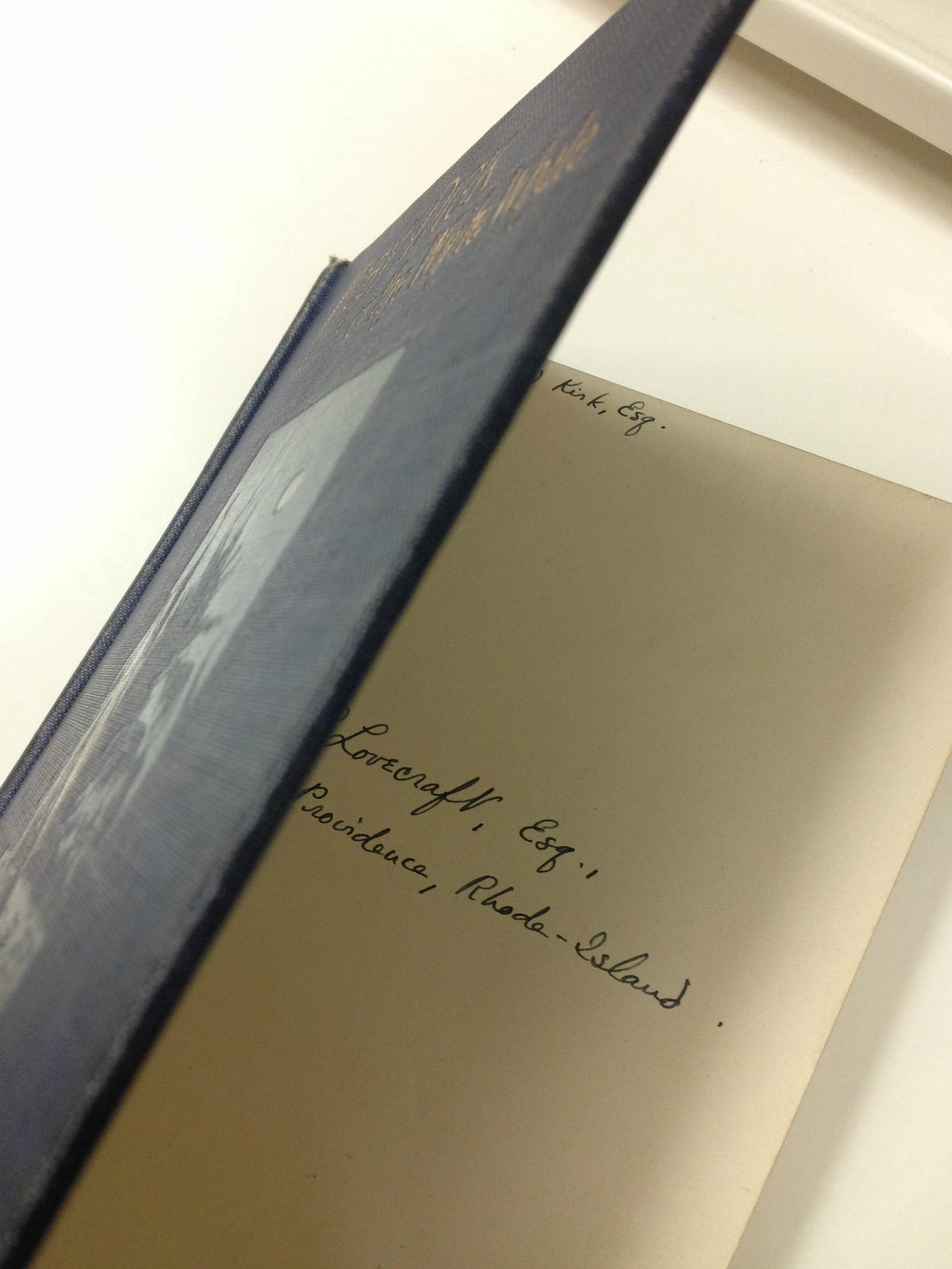

The book is not just loaded with words or tongues. Its also loaded with genres, or more accurately, different modes of literature. And one of the modes I particularly enjoyed this time around is, appropriately, the Weird. In ways long noted on forlorn and unspeakable subreddits, there is a decidedly Lovecraftian dimension to Melville’s Whale, which the Master of Providence did read and enjoy months before writing his game-changing “Call of Cthulhu.” We begin the novel with a sick soul, who may or may not be named after an Old Testament outcast, wandering through a macabre and fetid New England whale-town, following grim portents that lead him on towards a cursed ship doomed to confront a monster who sleeps or at least feeds, and presumably dreams, at the bottom of the sea. And that’s just the first couple of chapters.

What lies ahead are many moments of outright cosmic horror that puncture the novel. Take, for example, the famous scene when Pip loses his reason after being left alone bobbing in the water.

The sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, but drowned the infinite of his soul. Not drowned entirely, though. Rather carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad.

Or this description of a giant squid:

A vast pulpy mass, furlongs in length and breadth, of a glancing cream-color, lay floating on the water, innumerable long arms radiating from its centre, and curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas, as if blindly to clutch at any hapless object within reach. No perceptible face or front did it have; no conceivable token of either sensation or instinct; but undulated there on the billows, an unearthly, formless, chance-like apparition of life.

As with a low sucking sound it slowly disappeared again,…

Or later, when Ishmael is reflecting on the whale fossils that, like other relics of the ancient past, were eroding the confident claim of Biblical history still widely accepted in Melville’s day.

When I stand among these mighty Leviathan skeletons, skulls, tusks, jaws, ribs, and vertebræ, all characterized by partial resemblances to the existing breeds of sea-monsters; but at the same time bearing on the other hand similar affinities to the annihilated antechronical Leviathans, their incalculable seniors; I am, by a flood, borne back to that wondrous period, ere time itself can be said to have begun; for time began with man. Here Saturn’s grey chaos rolls over me, and I obtain dim, shuddering glimpses into those Polar eternities; when wedged bastions of ice pressed hard upon what are now the Tropics; and in all the 25,000 miles of this world’s circumference, not an inhabitable hand’s breadth of land was visible.

Lovecraft, of course, is all about those “dim, shuddering glimpses” into eternities. But Melville, unlike other 19th-century proto-Weird American masters like Poe or Hawthorne or old Charles Brockden Brown, draws many of his Gothic gnostic mysteries out of the close observation and careful appreciation for the natural and material world — the planet as cosmic conundrum.

Melville is a fascinating if skeptical weaver of the religious imagination, and Moby Dick is (in part) a book of pantheism, and polytheism, and prophecy, and dharma. But it is also a profoundly naturalistic book. This is why none of the chapters in the not-always-a-novel are boring — not the one about krill, not the one about the history of whaling, and certainly not the notorious one where Melville classifies whale species the way bookdealers classify physical volumes. Melville’s deep research in these chapters shows his appreciation for the naturalist eye, for combining observation, reason, skepticism, and imagination into the sorts of accounts that drive a Charles Darwin to upend the human story in the crisp light of the more-than-human world. Melville’s acute, almost journalistic appreciation for material processes also informs his devastating portrayal of the realities of the American whaling industy, which gives this book a depressing relevance in an era of extinction and catastrophic climate feedback. Remember: before there was petroleum, there was sperm oil, the central lubricant of early industrialism.

Melville also fully and deliriously recognizes the limits of naturalism — the false promises of “objective” language, the ultimate futility of scientific categories, and the inevitable mysteries that fringe our maps, whatever their accuracy. Ahab is not wrong to destroy his sextant. Here, in the margins, something anomalous still appears — ancient godforms, signs and portents, glimmers of a grim Beyond. Before us an enormous cetacean Enigma sky-hops and sounds above, beyond, and beneath the human horizon. Melville is an amphibian, one who can follow the logic of the land and the trackless drift of sea-being. That’s how he winds up writing some of the first passages of cosmic horror in American literature. More than that, he unrolls a foundational text, at once a scripture and an anatomy, of the other-than-rational view of the other-than-human world. This is what I, in High Weirdness, called weird naturalism: the respect for natural fact and the practice of attentive perception of the material cosmos, even as this gaze peers deeper, into the glittering and haunted void, the Abyss that stares back with a creaturely eye. Hello.

Other Upcoming Events

• Weird Academia

From Tuesday January 27 through Friday January 30, I will be at Indiana University in Bloomington to join the previously mentioned JF Martel, his Weird Studies partner Phil Ford, and a host of other thinky oddballs (including friends Jeff Kripal, Michael Garfield and Shannon Taggart) for Weird Academia, a gathering that will explore how serious engagement with the strange and the paranormal might find a real place within the contemporary humanities. Here are the three public events going down:

Tuesday, January 27, 4:30 - 6:30 pm

Gallery opening for Shannon Taggart’s Séance. McCalla School Gallery

An exhibition of Shannon’s amazing Spiritualist photography project Séance, with live music by the ever groovy Michael Garfield.

Wednesday, January 28, 7:00 pm

Ken Russell’s Altered States (1980), with a live episode of Weird Studies to follow. IU Cinema

Come hear JF and Phil riff in person after a showing of this excellent and deranged film. The event is free but ticketed. You can reserve your seat HERE.

Thursday, January 29, 7:00 pm

Weird Academia: A conversation with Phil Ford, J. F. Martel, Erik Davis, Jeffrey Kripal, Jacob Foster, Shannon Taggart, and Cat Hobaiter. Buskirk Chumley Theater

God knows what we all will conjure. This event is free but ticketed. You can reserve your seat HERE.

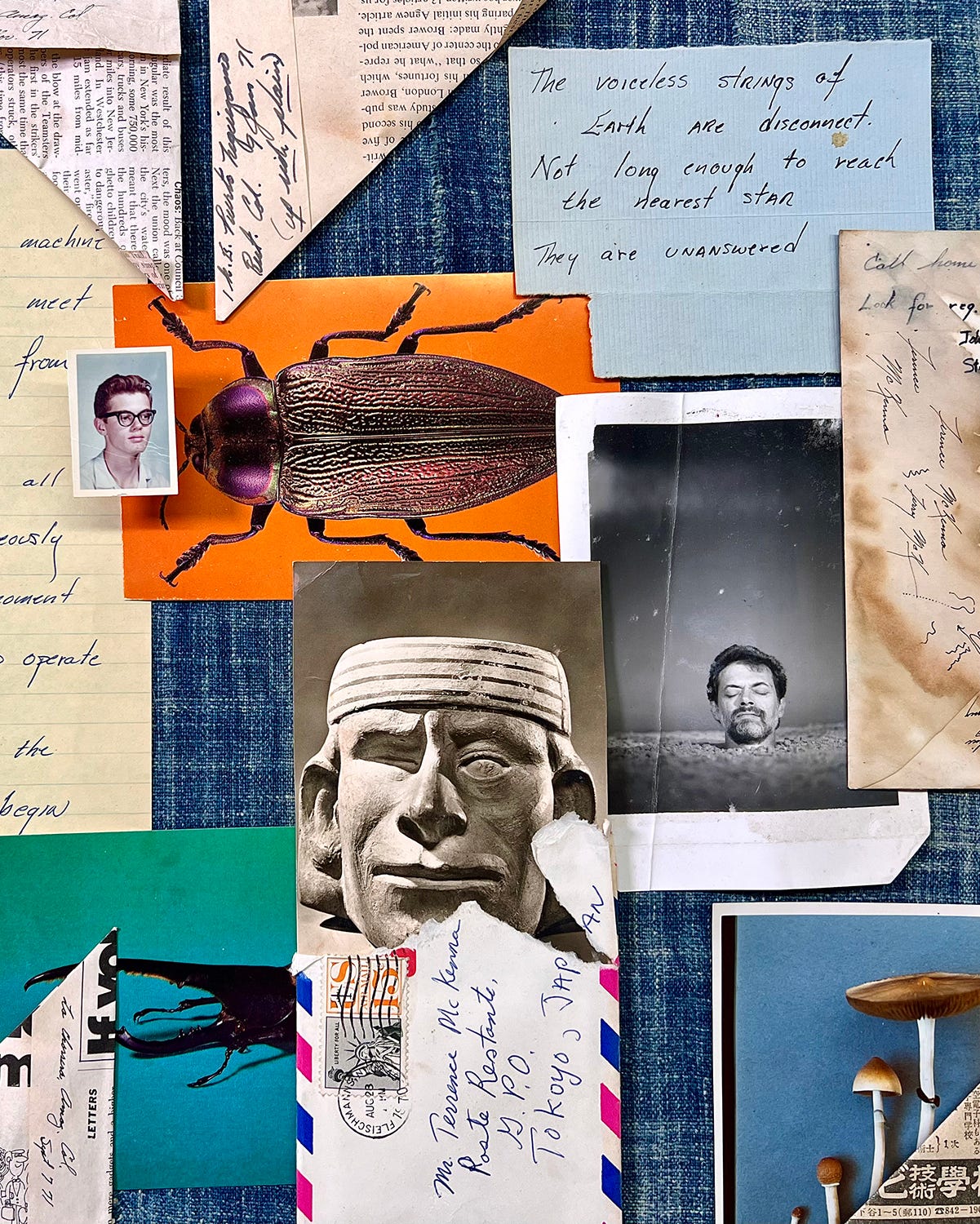

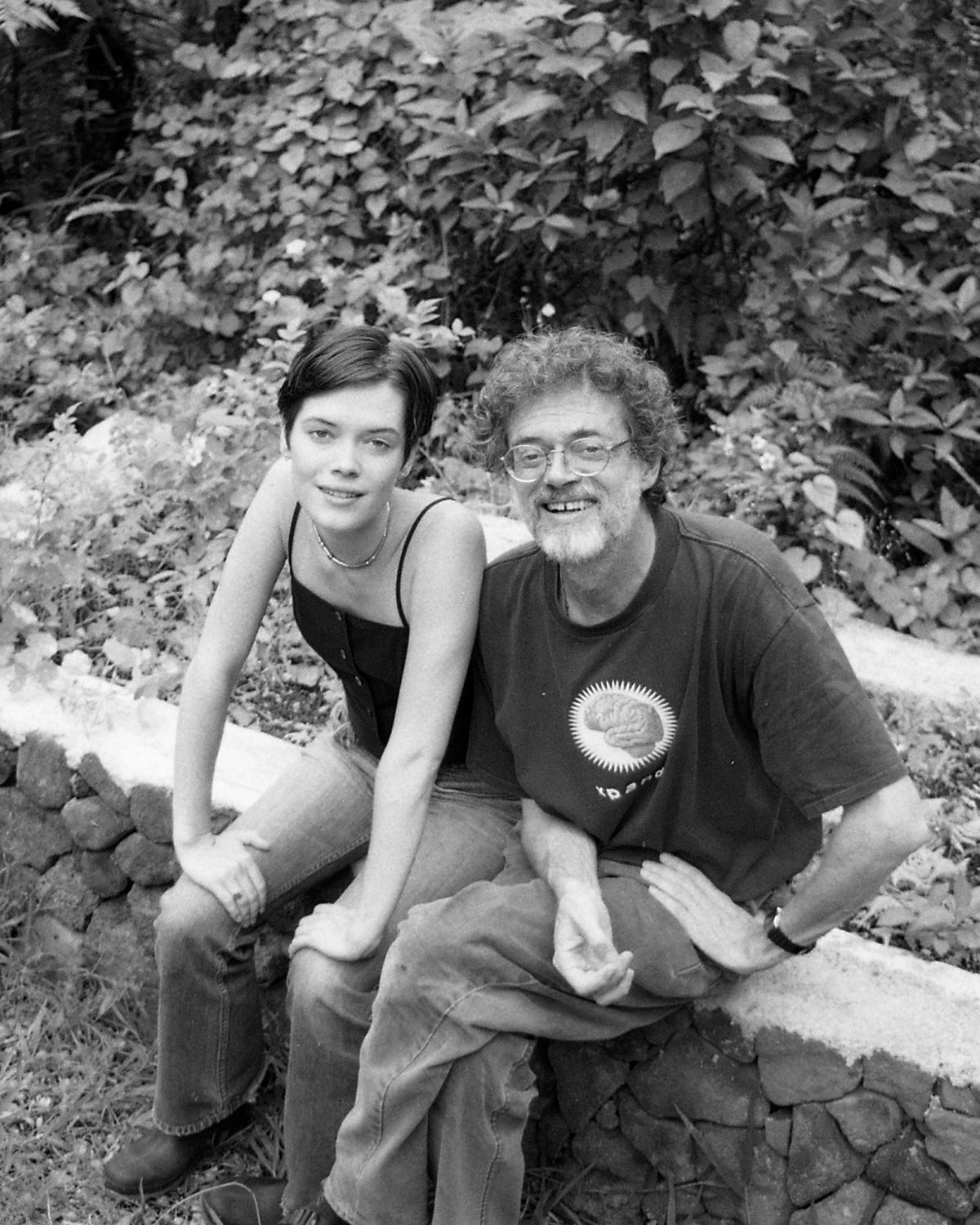

• Archiving Terence McKenna, a Chalice conversation with Klea McKenna

Over a quarter century after Terence McKenna’s death, his visions, voice, and “funny ideas” continue to loom large in a world now exploding with the apocalyptic novelties he foresaw. In 2024, Terence’s daughter, artist and photographer Klea McKenna, began gathering, digitizing, and interpreting her father’s work, intellectual legacy, and life story. I first met Klea when she was a teenager, and have followed her subsequent career with great appreciation. For this February’s Chalice — the Berkeley Alembic’s monthly psychedelic salon — Klea will provide a glimpse of the new Terence McKenna Archive, sharing elements of her process and digging out some gems from the collection’s thousands of letters, lecture notes, journal pages, photos, and butterfly specimens. Hopefully Klea will talk a bit about her own extraordinary photography work, especially her early work The Butterfly Hunter, a response to her father’s time in Indonesia. Join us at the Alembic on Wednesday, February 4th, at 7pm. Links for in-person and online.

Recent Appearances

• The Unseen Internet

All the wireheads were out in force for a recent Alembic event celebrating the Internet scholar Shira Chess’s new book, The Unseen Internet: Conjuring the Occult in Digital Discourse. Along with looking at today’s WitchTok, reality-shifts, and glitch culture, Chess tracks the weirdness back to the 1990s, when many of the people shaping early Internet culture were also hacking reality, practicing Technopaganism, and engaging in other forms of alternative spiritualities that intersected with emerging technologies. And some of those people were present at the event, including myself, Paco Nathan (Machine Learning, AI expert and editor of the great FringeWare Review), Mark Pesce (Co-inventor of VRML and futurist), and R.U. Sirius (Mondo 2000). Together we wrangled with consensus reality. You judge who survived.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. More than anything, I want to resonate with readers. If you would like to show support, the best thing is to subscribe and to forward my posts to friends or colleagues. You are also welcome to consider a paid subscription, and you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

Dipping into this essay as I prep for tonight's lecture (though the L-word misses your wonderfully convivial style) -- I just wanted to write & convey my heartfelt thanks. I had a truly great English professor in college, who taught as his spirit bade him, and in some ways he both saved my life and set a course for it. You and JF are bringing memories of his class (and person) back to me in a vivid rush, with all kinds of new color and depth. And...and! ...Shining all that light on and into the book that re-fired the reading habit in me, in the midst of my long sojourn in the blue-suited, beige-cubicled world. On lecture and discussion days I'm all but skipping into the kitchen to pour my coffee. For that alone, this not-quite-old-enough-to-be-a-real hippie hippie thanks you from the bottom of his heart!

One of my all-time favorite books. Every time a publisher tells me I can’t do something, I counter with, “Melville did.”