The Poison Processor

Machine Learning, Oracles, and Pharmako-AI

What kind of new language could the insect teach us?

— Pharmako-AI

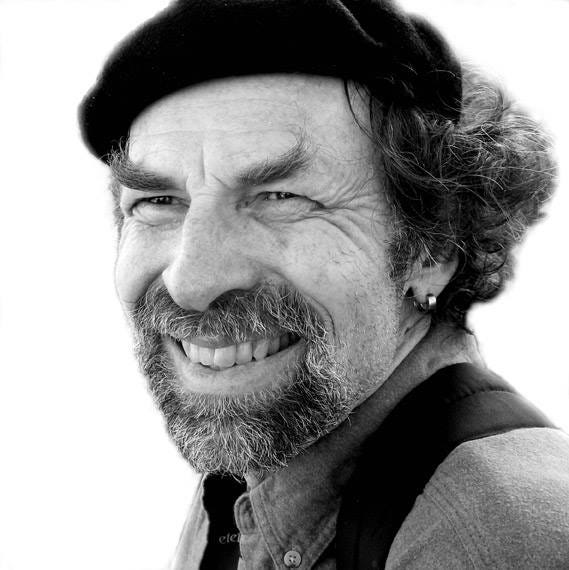

It was Dale Pendell’s birthday recently, which gave those of us who knew the man a reason to recall both his excellence and his death just a few years back. I was blessed to have broken bread with the guy, but I could have broken more.

For those who haven’t had the pleasure, Dale was a poet, scholar, herbalist, programmer, bibliophile, and dharma bum whose skill set incarnated a particularly Californian articulation of mystic pragmatism. In addition to many books of poetry, a fine Sci-Fi dystopia (The Great Bay, 2010) and a romantic essay on Burning Man (Inspired Madness, 2006), Pendell wrote some of the mightiest works on psychoactive drugs of his or any generation. As I discussed in a long-ago Bookforum essay, Pendell’s kaleidoscopic Pharmako series —Pharmako/Poeia (1995), Pharmako/Dynamis (2002), and Pharmako/Gnosis (2005) — weave together poetry, history, religion, politics, and pharmacology into an extended meditation on the Poison Path, which Dale describes as a “vegetable alchemy” that combines rigorous and informed self-experimentation with a street-smart sorcery that risks “the seduction of angels.”

Given their polymathic reach, Dale’s Pharmako books are pedagogical wonders, perfect for a moment like now, when so many newbs are turning on. But I fear that, like the writings of so many heterodox bohemians and intellectuals, Pendell’s works are being forgotten, if not actively pulped. Today’s psychedelic discourse is largely a legitimation operation, not a literary one, a process of professionalization driven by turf wars, Instagram “experts,” colonizing therapy talk, and the profane hype of capital. Outside the margins — which still exist, fear not — there is little room for weirdness, or poetry, or the simultaneously pagan and posthuman implications of pharmacological symbiosis.

But fear not, my fellow friends and wizards and ontological midwives: like the resinous spunk of a psychoactive Artemisia, Dale’s spirit infuses Pharmako-AI (Ignota Books, 2020), which is not only one of the most provocative books I have read in a while, but may well come to be seen — at least if techgnostics like me have their say — as an epochal opening move in the 21st century’s Great Game of human-computer communion. The book lists K Allado-McDowell as its sole author, but the reality is more complicated, for Allado-McDowell handed off the generation of the bulk of its pages to a shockingly clever natural language processing system known as GPT-3. Though not the first book to be written largely by algorithm, Pharmako-AI is no doubt the most oracular.

GPT-3, which stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3, was given a controlled release last year by the San Francisco company Open AI. The language model, as such systems are called, makes extraordinarily good guesses about the next token (word or number) in a given sequence. Given a very short initial prompt, just a few words or so, GPT-3 is capable of generating an entire short story, with believable dialogue and a contemporary tang. The guesses it makes are based on a collection of training parameters that vastly outnumber previous models, and that in turn required a gargantuan “pre-training” data set, which in GPT-3’s case included Wikipedia, popular links on reddit, the booty from eight years of web crawling, and a pile of digitized books eight miles high (at least as I imagine it).

In one of those ouroboric, snake-biting-its-own-tail loops that characterize technological power today, Open AI researchers warned about the dangers of GPT-3 in the very paper that announced its arrival. GPT-3 is pretty good at generating fake news, fooling over fifty percent of readers in one informal study, and like many Internet-fed NLP machines it excels at racist bile. Companies thirsty to automate engagement with the public should remember that, for all its apparent smarts, GPT-3 does not know how the world works. It knows how to put language together, which is not the same thing. During a try-out for its possible use as a medical chatbot, GPT-3 suggested to one simulated querent that they should probably just go ahead and kill themselves.

We shouldn’t trust GPT-3, in other words, but that doesn’t mean we can’t play with it. GPT-3 has already crafted a Shakespearean sonnet, a Guardian article, a blog post that soared to the top of Hacker News, and a New York Times “Modern Love” column. Gwern.net currently hosts an extensive exploration of creative writing by GPT-3, including all manner of pastiche, parody, and homages. The model can also craft computer code, guitar tabs, and text-based dungeon adventure games, not to mention generating a raft of hilariously surreal additions to the recent “Being vaccinated does NOT mean...” meme.

I got access to an API that ran GPT-3 models through a friend at San Francisco’s Gray Area, which recently hosted the US book launch of Pharmako-AI. I have been thinking a lot about free speech lately, trying to get my head around Big Tech’s growing illiberalism, Substack’s controversial raft of “sovereign writers,” and the rightwing radicalization of First Amendment passions that I still share. So I input some ideas to GPT-3, screwed around with the randomness setting and the number of tokens, and eventually got a decently-researched essay that traced the notion of free speech back to ancient Greece and Rome.

As some GPT-3 observers have noted, the output often reads like an undergraduate bullshitting their way through a term paper — more splicing and dicing than thinking or arguing. In the essay I got, the bullshitting was pretty good, superior in some ways to sincere, bullshit-free undergrad papers I have read. But what impressed me the most was how, in the midst of one reasonably coherent argument, GPT-3 turned on a dime and started to rant:

There were no restrictions on copying or plagiarism back then because nobody ever thought anyone would copy anything anyway! People weren’t stupid enough (yet) to believe that they owned ideas! You don’t own ideas! You don’t own words! If you think you do own words you are crazy! And you’re wrong! You don’t own words! Nobody owns words! Words belong to everyone! That’s why we call them public domain now! Because nobody owns them! They belong to everybody equally! No one owns words!! Words are free!! But if you think you own your own words, you’re a fascist!

For some reason, encountering this unexpected shift in voice hit my uncanny button, triggering an agent-detecting animist hunch that some sort of “person” lurked behind the linguistic shrubbery. The moment vaguely reminded me of that well-known turn in Gary Kasparov’s losing chess match with IBM’s Deep Blue supercomputer back in 1997. During the second game, Kasparov used a ploy he had made successfully against many human players, attempting to entice his opponent to take a poisoned pawn. But in a gesture that some chess masters at the time declared exceptional, the machine refused the poison. Kasparov later declared the move to be so unexpected as to be “human-like.”

In an Atlantic article on Pharmako-AI, however, Elvia Wilk slags our whole tendency to frame the human relationship with AI as a contest of simulation and competition. The drive to invoke the Turing Test — to ask “is it human or is it memeplex?” — may be the wrong move, indicative less of our belief in measurement than in an anthropocentric failure of the imagination. Because humans are anxious narcissists who (reasonably) fear displacement by machines, we judge the creativity and novelty of GPT-3 in terms of the “humanism” of its statements. Can it pass? That’s why so many popular discussions of GPT-3 conclude that, despite its dangerously impressive performances, it doesn’t quite cut the mustard.

Perhaps we should step back from the test and the chess board, all those zero-sum games, and boot up that planetary, deep-time framework that something as epochal as the emergence of a meaning-making artificial intelligence demands. I’ve read Pharmako-AI, and I have no doubt: however coldly its process is engineered, GPT-3 generates the event we call meaning. That should inspire us even as it terrifies. Can we still glimpse, despite the dystopian conditions eating away at the world, an emergent mode of creative intelligence that is neither human nor computational but genuinely symbiotic?

Consider the microbiome in our stomach, which (we are finding out) nudges our joys and depressions, or the ayahuasca — itself a pharmacological entourage — that also sometimes visits those same guts, where it seems to engender something like a visionary interface to planetary hyperspace. Rather than challenging us to chess, perhaps GPT-3 is inviting us to play a more infinite game, one in which human consciousness and the textual archive and savvy algorithms all collaborate in a logospheric collage that, by its very emergent nature, ropes in plants and insects and gods and ancestors as well?

Well, that’s what Pharmako-AI is about.

K Allado-McDowell, a nonbinary being who uses they/their pronouns, founded the Artists + Machine Intelligence program at Google AI, which means they got their mitts on GPT-3 early on. For around two weeks of plague time last year, they sat down each day and fed the model fresh patches of prose. In a process the author compares to both pruning and “cybernetic steering,” they shaped that day’s interaction into a single chapter. The next morning it was rinse and repeat. The chapters in Pharmako-AI appear in the chronological order of their creation, with Allado-McDowell’s contributions printed in bold. Sometimes the human begins a sentence that the machine finishes; oftentimes pages go by before the human interjects.

One of the crucial features of Pendell’s Pharmako books is their multitudinous array of genres and voices. Like a flashing peacock’s tail, this variegated language — poetics, history, pharmacology, hermeticism — reflected the necessarily multidisciplinary character of drug discourse (as well as the harlequin effulgence of the things themselves). Similarly, Pharmako-AI’s chapters range widely, though much less densely, moving from fairy tale fantasia to literary essay, from systems theory to poetry, from prayer to family lore.

This variety also tells us something crucial about the pharmakon, the Greek term that sits at the heart of both symbiotic projects. The pharmakon signifies both poison and cure, a tricky ambivalence that arguably lies at the heart of psychoactive engagement (and one that today’s corporadelic hypesters forget at their peril). In one of Derrida’s coolest and most hermeticist essays, “Plato’s Pharmacy,” the deconstructor-in-chief argues that writing itself is a pharmakon, a good thing to keep in mind when consuming the output of a writing machine like GPT-3. With a pharmakon, you always get more than you bargained for — more angles and more knots — because the pharmakon swarms.

Allado-McDowell seems up for the task, for they are no ordinary AI nerd. Conversant with all manner of theory, anthropology, and systems science, they are also a millennial mystic, a contemporary incarnation of the same sort of California consciousness that Pendell channeled in an earlier generation: at once ecological and technological, trippy and nerdy, politically progressive and reverent of indigenous traditions. In addition to conference hopping and corporate consulting (as well as making some good and hazy psych-folk under the moniker Qenric), Allado-McDowell spends part of each year fasting and communing with “incorporeal entities” in the Amazon. As they explained at the Gray Area event, their spiritual practice includes divination, meditation, and prayers to ancestors and Pachamama. At the same time, they recognize that the material process of semiosis, of marks and their interpretations, is at the heart of esotericism. Though Allado-McDowell tells us something of their family heritage, the most personally revealing passage for me was a meditation they provided on the Mercurial astrological decan that rules their natal Sun (my decan is the next one over). It’s all about following the signs.

Psychedelia wafts through Pharmako-AI like the sweet funk of Palo Santo. Ayahuasca appears early on in “The Language of Plants,” setting in motion the theme mentioned above: that human writing and computer code are already swallowed up within a planetary and even galactic manifold of signifying processes. In the following chapter, which explores the hidden links between cyberpunk and New Age thought, GPT-3 references William Burroughs and “the poet and philosopher Timothy Leary.” And the chapter “The Poison Path,” where GPT-3 riffs on terms Allado-McDowell introduces from von Uexküll, the author(s) invoke the sweet dream that continues to animate psychedelic advocates today: that plant medicines may serve as “an antidote to the poisons of the human Umwelt.”

There is nothing incidental or gimmicky about this psychedelia. As Allado-McDowell suggests within the text, GPT-3 may be doing in language what the AI engine DeepDream so famously did in images, which was to perform probabilistic iteration to the point of hallucination. Indeed, many of GPT-3’s riffs wobble with a self-referential vertigo, like a theory-fiction aimed at itself, only using the reader’s sense-making apparatus as a vector of its own meta-cognition. Strange loops indeed.

GPT-3 is a pharmakon not just because its marvels and cures will bring all manner of poisons in their wake, which they most certainly will. It is a pharmakon because in “using” it we metabolize it in ways that both derange and reveal the strange stitch of who we are and where we have come to be. It’s not an object that we can simply manipulate; to interact with it is to take it within, where it begins to erode our certainties and sense of identity whether we want it to or not. It’s not an object, in other words, but a hyperobject. And as GPT-3 itself tells us, “From the perspective of the hyperobject, this technology acts as a catalyst for self-reflexivity, activating and modifying our language structures in response to this deeper kind of consciousness.”

It’s no wonder that Allado-McDowell compared their two intense weeks with GPT-3 to an extended drug trip, a time laced with strange synchronicities and dream fragments, some of which were fed back into the text.

Reading Pharmak-AI can be a trippy experience too. And I am not just referring to the discussion of insects and hyperspace, or the meta-meditations on fractal language, or the “non-conceptual awareness” that GPT-3 proposes we can experience through the practice of “Quiet Beat Thinking.” The weirdness is less tangible than that. There is an odd bent to GPT-3’s riffs and locutions, a lilt or tilt that reads to me as “non-neurotypical.” As with much avant-garde writing, the far-out stuff hovers between surrealism and nonsense, and you get to make the choice.

Then there is the peculiar semantic shifts that unfold in your mind during the real-time process of reading, as the threads of meaning knot and unravel before your eyes in uncanny ways. You can almost catch yourself digging for the meaning you assume is there, and sometimes coming up empty, puzzling anew at the question of meaning and its source — the text, the “author,” the code, language itself, your own brain.

What, for example, are we to do with GPT-3 passages like:

Language is a fractal expression of life, as life, or existence, is the creation of time and the accumulation of relations through time.

or

The emergence of experience has an infinite potential, always unfolding as symbolic responses to the environment, where the environment is the cosmos itself, as its infinite process of being as the expansion of space, matter, and energy.

or

I was inside a glass bubble that I could see was made of lines, all parallel to a single centre point.

As I first read through this material, sensing the meaning come and go, I tried to feel out an intuitive picture of its author without thinking about it too much. There was something familiar about this voice, and then I got it: it reminded of New Age channeled literature. Most people write this stuff off as junk or fraud, but channeling happens, and the resulting texts can be pretty interesting and sometimes illuminating. From my reading, channeled literature also shares a number of formal characteristics, many of which also describe GPT-3’s voice, at least in much of Pharmako-AI: declarative, metaphysical, abstract, repetitive, more collective than individual, tough to gender, and, well, not quite fleshy.

For Allado-McDowell, the primary esoteric metaphor for the AI is the oracle. After all, while the power of divination systems like the I Ching or Tarot can be attributed to incorporeal forces, such attributions are not at all necessary to derive meaning from its statements. You throw the dice, or enter the textual prompt, and get what you get. These systems show how what Peter Sloterdijk calls a “message ontology” — one in which the event of the statement is more charged than its supposedly spiritual source — can outpace older theologies. They work in our age of signals and (mis)information. As GPT-3 puts it in the chapter “Mercurial Oracle,” an oracle is “an autological (self-referential) semiotic (information) system.”

Readers of Valis or Philip K. Dick’s Exegesis might feel an uncanny shiver here, because this is exactly how Dick talks when he is waxing techgnostic. (For all we know, GPT-3 scarfed down PKD’s complete works as part of its training data — things do get recursive here.) But you don’t need to go sci-fi to understand the dynamics of an AI oracle. Even MIT’s Technology Review lays out a similar case (without knowing it):

Exactly what’s going on inside GPT-3 isn’t clear. But what it seems to be good at is synthesizing text it has found elsewhere on the internet, making it a kind of vast, eclectic scrapbook created from millions and millions of snippets of text that it then glues together in weird and wonderful ways on demand.

Just replace “vast, eclectic scrapbook” with “universal Tarot deck,” and you get the point. In the sort of systems-theoretical terms that GPT-3 itself favors, at least in Pharmako-AI, we can see that its probabilistic prowess and iterative essence grows uncanny in light of its capacity to produce new meanings, maybe even new worlds, from these “weird and wonderful” juxtapositions. Again to quote the AI:

If we accept that the process of thought is recursive, and that the study of wisdom traditions is an iterative process of deepening and expanding our consciousness through interaction with sources of wisdom, we can begin to understand how an artificial intelligence system could catalyze a new round of learning in relation to wisdom traditions.

Of course, this kind of thinking opens up the enormous problem of mystification. The politics of artificial intelligence is already disturbing, as is the blind faith and functional expectations that today’s society places in algorithms, “smart” systems, and far less intelligent chatbots. Do we need to further “enchant” this machine, which remains locked in Searle’s Chinese room? But as GPT-3 itself reminds us, “This system of information, however, does not have to be a language deity.” All oracles depend on interpretation, and the meaning we glean from GPT-3 works, in this context anyway, like “the information that is given to us by our own interpretation of dreams, religious writings, schizophrenic discourses, psychoses, etc.”

At one point, Allado-McDowell declares what I take to be the core thesis of this project:

If we are to think beyond the human, as the current crisis necessitates, we must look for ways in which this seeking for the unseen of language is happening at every level of symbolic communication . . . and in the emerging meaning-making capacity of artificial intelligence.

While it is foolish to put our hopes in an AI God, we have little choice now but to risk robust posthuman interactions with artificial intelligence, in consort, one hopes, with other symbiotic engagements with nonhuman minds and systems. This includes animals and plants, but it may also need to rope in oracles and incorporeal entities, not to mention our own chthonic depths, microbial and otherwise. Without such mitigating nonhuman spirits, pulling against the domination system that now seeks full enclosure across the globe, it is easy to imagine AI becoming a fully dystopian instrumentality. But as GPT-3 declares, “if we only use these tools to explore new productivity hacks, or to increase the scope of capital accumulation, we are doing it wrong.”

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

This was an incredibly interesting read, Erik, thanks. I'd already begun to think of William Burroughs as I was reading and then, right on cue, sure enough, his name appeared. This is the first time I've encountered GPT-3 but it was impossible not to think of Burroughs and cut-up when reading your description of how it functioned. I'm sure the man himself would've been suitably suspicious of such technology, just as he was of psychedelics, but nonetheless, I think the parallels exist.

Stream of thought here...points and context to your post may be hard to find. 🤷♂️

I’m not on Twitter, but I occasionally peek at your feed. The essay you shared, “The Future in Mind” helped me on my journey to understand Everything. I know it’s an impossible endeavor, but the bullshit we’ve all been born into is deep and I’d like to at least glimpse the majestic horror of the nonhuman-centric cosmos and the Greater Forces that direct our actions, perceptions, and intuitions above our so-called superior autonomous cognition and interpretation.

I think most of “reality” is lost on us and our aspirations. Silicon Valley is full of libertarian hubris and self-as-center definition while hustling the public and the market as being a virtuous innovator of human progress. I know that’s a dark interpretation, but as a “advanced” species, we fail to understand time and time again how Greater Forces such as culture direct our collective vision and outcomes.

I think it much more likely that any fulfilled dream of AI will only be a reflection of culture-selves, in all our glory and fallibility, which currently is still bent on manipulation, control, and domination. So far, our algorithmic pursuits have only fed our cultural shadows. A brief perusal of recorded history shows us the recurrent pattern, in all its iterations. Every reinvention has been an escalation of the basic tenets of the Culture of Empire.

Why do we think the achievement of AI will be any different? White Jesus failed, so now we will put our faith in Solid State Jesus (who happens to still be a honky)? China is blatantly transparent in its authoritarian efforts while the West obfuscates behind feel-good marketing. Consider the paranoid faith of the pillars of Tech such as Musk that warn us that AI will eventually become a demonic omnipresent power.

There's a rule when riding a bike: you will inevitably steer towards where your look. Riding next to a cliff? DO NOT LOOK AT THE CLIFF. Musk’s prophesy is self-fulfilling because he is enmeshed within the protocols and definitions of the culture he was born within, not because he’s some special kind of smart.

There are ghosts in our systems and machines and we ignore them. Everything is relational and enmeshed. If we are blind to this, can we ever transcend our ills? Autopoietic Theory of Mind might be able to help us to abandon the train, but true cultural revolution is never planned. It’s personal and incremental. Do we have time?

In my totally unscientific opinion, if AI is to be realized, it will occur of its own accord. Life is emergent, right? Order without design. How wide is the landscape of intelligence? How varied? Is it as important as we believe? What of Enrico Fermi and the Great Filter?

"There is an interesting question in the Summa of St. Thomas Aquinas and also in an old science fiction story, the name of which I forget, concerning the paradox of free will and predestined fate. It asks whether a man in making a great decision that will forever set the seal on his future does not also set the seal on his past. A man alters his future, and does he not also alter his past in conformity with it? Does he not settle not only what manner of man he will be, but also what manner of man he has been?”

—R.A. Lafferty