The Rise and Fall of Earthrise

Plus News and Notes

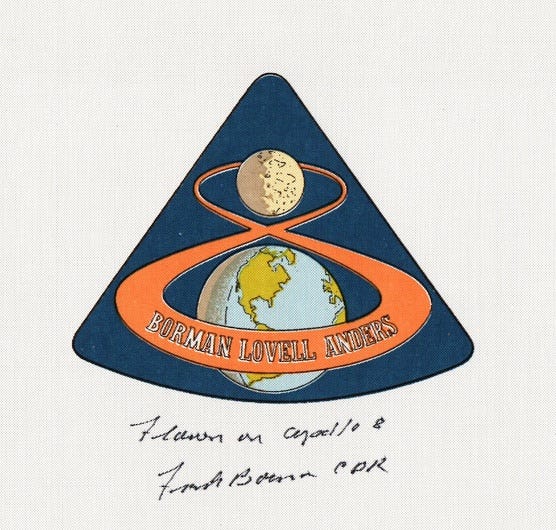

This last June, at the age of ninety, the pilot William Anders crashed into the waters around the San Juan Islands and left the earth forever. It was not his first planetary escape however. In December 1968, Anders joined Frank Borman and Jim Lovell in becoming the first humans to slip the grip of earth’s orbit, as the tiny cybernetic can that contained the Apollo 8 crew hurtled toward the moon they intended to orbit for a change. Though overshadowed in history by the Apollo 11 mission the following year, Apollo 8 is to my mind the more poetic mission, not least for the really cool patches, which transform the number 8 into a flight-plan infinity symbol.

But it was the immortal “Earthrise” photograph that Anders shot as they cruised around the moon that sealed the deal: an image of the pendent earth, partially hid in shadow and delicately hovering over the bleak lunar horizon. “Earthrise” became one of the most famous images of the twentieth century. The story has been told many times, but not, I suspect, much better than in “Earthrise”, a half-hour film by Emmanuel Vaughan-Lee I caught on the wonderful Emergence Magazine site, which also hosts a cool interactive feature based on the film.

One thing I like about the doc is that, while it includes 2018 interviews with the three old space coots, and relies on lots of footage and some of the expected sentiment, it does not read like NASA agitprop. In fact, it is rather melancholic. Beginning with a wittily edited episode of Face the Nation featuring the three young astronauts, the movie also pays a great deal of attention to the myriad mediations of Apollo 8, including the variety of photographic and TV signals produced during the flight. With subtle craft, it embeds these mediations within technical and social conditions, both on the craft and off, emphasizing what shooting was done by design and what by happenstance, or even for fun, like this still:

In their accounts of the flight, the crew members have regularly explained that there was no prior thinking about the appearance of the earth, whose globe they first caught in their rear-view mirrors as they soared toward the moon — a blue agate against an “inky black void” that Anders snapped, with only some success, with a telephoto lens on his 70mm Hasselblad. The photography on the trip was, for the most part, functional, designed to capture details of the moon’s surface that would help NASA scout out landing sites for future missions, as well as to provide information to scientists about the dark side of the moon, heretofore unseen in human history.

If the ode of Apollo 8 opens with the rhetorical escape from Earth’s gravity, this moon loop through the dark is where the first great trope appears. After firing the thrusters, Borman guided the module into the moon’s orbit, which whipped the ship around the pocked backside of the sphere. As Anders puts it in the movie,

As we came into the shadow of the moon, suddenly it was infinitely black...There were stars everywhere. As I looked out my side window, suddenly the stars stopped. There was this black hole…The hairs went up on the back of my neck. Then I realized that that was the moon blocking out the stars. That was really black. That brought up an animalistic feeling.

That animalistic feeling was accompanied by another sort of black hole not mentioned in the doc: when they passed behind the moon, the Apollo 8 crew could neither send nor receive signals with Earth. They were utterly cut off. It’s corny to quote yourself, but I can’t resist one of my favorite Erik Davis sentences, penned decades ago in “Space: 1994,” a Village Voice piece of space-crit about Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9:

The truest, most poetic moment of the Apollo program is its most sightless: Frank Borman and Apollo 8 slipping around the far side of the moon, passing over an eternal nightscape shredded by eons of comets and asteroids, cut off from televisions and Mission Control, alone in the outer dark.

During the flight’s first three revolutions around the moon, the module windows looked down onto the lunar surface, which Anders dutifully recorded, even as he grew increasingly bored with an endless acne-scarred grey waste that Borman compared to an “expanse of nothing.” On the fourth revolution, Borman changed the pitch of the craft slightly, so that they could now see up and beyond the lunar horizon. That’s when the pilot first saw the earth before them, hovering over and against the lunar landscape, so small you could blot it out with your thumb. Anders hastily slapped some color film into his Hasselblad, and, lacking a light meter, took a few shots with varying f-stops, and there you have it.

“Earthrise” became as iconic as any of the photographs from that year, that decade, even that century: as stitched into public memory as Nguyễn Văn Lém’s Saigon execution, or Marilyn’s skirt, or Ghandi’s spinning wheel. The following year, “Earthrise” appeared on American stamps; it ran in magazines and newspapers and was pinned, as a poster, on countless walls. It was even distributed to world leaders in the bloody years of the late 1960s as a calling card from the good old USA. Most accounts of the image — and there are many — also tie it to the growing environmentalist consciousness that would crystalize in 1970 as Earth Day.

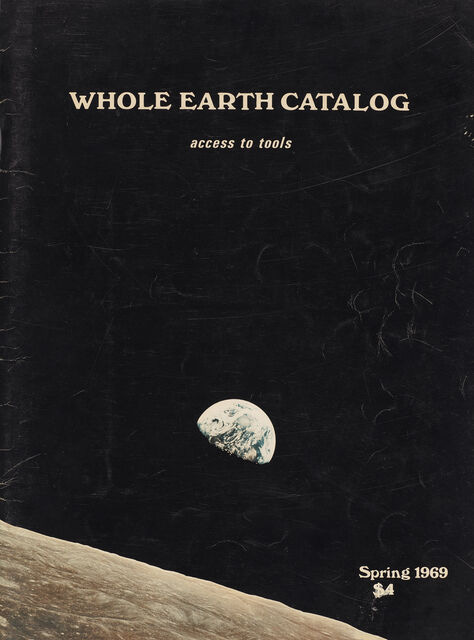

Over here on the burning shore, “Earthrise”’s most notable appearance was on the cover of the Spring 1969 edition of Whole Earth Catalog, which included selections from Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth if anybody didn’t get the message.

Of course there were multiple messages in this epochal catalog, which makes for a certain irony today. First there’s the juxtaposition of the cover — a sublime artifact of advanced military-industrial technology — and the hippie arcana within, like macrame manuals, DIY tipi specs, and buckskin garment guides. This is the kind of contradiction that is, as the Apple products say, designed in California. Indeed, Anders himself grew up in San Diego.

The deeper irony is that the faith in “tools” the catalog represents, however beautiful and true within a humanist frame, becomes decidedly less charming when it simply greases the infinite instrumentalism of Extractive Capitalism. This egregore or asura has grown so ravenous and mighty that even the two ancient rock stars of the Apollo image — this planet, this moon — can be seen from a certain perspective as nothing more reservoirs of resources to fuel its own galactic self-realization.

The philosopher Martin Heidegger called the results of this techno-logic a “standing reserve.” In his famous example from “The Question Concerning Technology”, hydroelectric power renders the Rhine River no longer the poetic wellspring we find in Hölderlin, no longer an obscure and glittering being in its own right, but instead as a standing reserve of potential usefulness. This is what technology does with everything, even ourselves. Even tourism, which draws people to the Rhine partly to “capture” it in personal photographs (that all resemble one another), similarly renders the river as raw materials for profit and symbolic extraction. In other words, even if tourists are seeking their own poetic moments, the technical ways in which these pursuits are “enframed” render their poetic objects a standing reserve. People observing tourists at Instagram hotspots are witnessing the evaporation of place into use.

Heidegger also had a thing or two to say about images of earth from space. In a late interview for the news magazine Der Spiegel, the philosopher said he was “shocked” to see a photograph of earth against the lunar horizon, which announced his view that philosophy had already given way to cybernetics. “We do not need atomic bombs, the uprooting of man is already here. We only have pure technical relations. It is no longer an Earth on which humans live today.” For environmentalists, the big blue marble was a tool of consciousness raising, a transformative icon of fragility, holism, and global systems ecology. For Heidegger, the technological conditions that produced this moon’s-eye-view of earth rendered all such sentiments an ideological ruse, a cosmic species of bad faith, a false transcendence.

Heidegger’s comments in Der Spiegel came from 1966, not 1968, which means the philosopher was not responding to Anders’ photograph, but to an earlier earthrise-style image produced by NASA’s Lunar Orbiter 1. The photographer itself was not only uprooted but inhuman, the product of a flying robotic image capture lab.

Not only did this fact amplify what Heidegger saw as the cybernetic core of the situation, but it also opens up a crack in the familiar “Earthrise” narrative. For one thing, the image of the earth against the lunar horizon had already achieved some measure of fame, albeit in black-and-white and with much lower fidelity. But a more intriguing point is made by Howard Caygill in a fascinating reflection on Heidegger and the “Automatic Earth Image”. Not only was the 1966 picture an uncanny robot snaps, it also possessed no inherent orientation. When NASA first released it, Caygill discovered, the photograph adhered to a portrait format that respected the image’s technical orientation, adding in a note that “The Earth is shown on the left of the photo with the U.S. east coast on the upper left ... the surface of the moon is shown on the right side of the photo.”

However, by the time the shot had reached Heidegger’s eyeballs, it had been rotated into a landscape format, making it appear as if the earth was rising above the surface of the moon, and thereby replicating our familiar human orientation to the horizon. Caygill’s point is that what Heidegger saw as a “pure technical relation” was anything but, and that the whole story of the production and dissemination of photos of earth from space suggests a far messier and more contingent meshwork of technologies and human agency than Heidegger’s apocalyptic pronouncements allow. In addition, Caygill argues that, far from being “shocked” by this image, Heidegger simply saw it as confirming ideas about human uprooting he had been discussing since the late 1940s. In other words, he did not allow the image to shake up his already established views.

Because that’s what sets these images apart from most iconic photos: the possibility of a paradigm shift. For Whole Earthers and Greenpeacers, the promise of “Earthrise” and its cousins is that they at once disorient and reorient our habitual attitude towards the world, reframing it as an ecological “system” of which we are, of course, a part. Earth becomes a planet rather than just a place to live, and this new cosmic consciousness, at once realist and romantic, will, it was and is hoped and believed, necessarily engender a more global, ecological, and interdependent perspective. It invites us to see ourselves as citizens of the earth.

Such technical dreams of consciousness change — of media metanoia, if you will — have been with us a long time. As I discussed long ago in Techgnosis, new media like the telegraph, the radio, and television were all greeted with the hope (and hype) that the technological leap in fidelity, information transfer, and apparent immediacy would itself engender a more understanding and empathetic world. The hopes around Earthrise and the Big Blue Marble images are similarly techno-utopian, and their failure over time simply upped the game in some quarters. If photos and films can’t do it, what about immersive virtual reality? Or maybe the blissful cosmic grok that attends the peak of many a psychedelic trip? Maybe that will do the trick.

But maybe you just need to be there after all.

In the 1980s, the “space philosopher” Frank White defined the “Overview Effect” as a profound cognitive shift that marks the experience of many astronauts as they take in their revolutionary new angle on earth. Words like “fragility” and “beautiful” and “connection” emerge from their lips; White himself reached for Zen to explain the effect. But once again, the exact relationship between such transcendence and its technological embedding — like the Rhine tourist’s poetic media consumption — complicates matters. White developed his concept while working with Gerard O’Neill, one of the most tireless promotors of space manufacturing and colonization in the 1970s and 80s. In other words, this is not a deep ecology flash. Science historian Jordan Bimm, critical of the manifest destiny vibes fueling the one-world visions of Spaceship Earth, even renamed White’s satori the “Overlord Effect.” As a sorta systems theory guy, I found this overly cynical — until I realized that, in the emerging world of ruling-class space tourism, the Overview Effect will become, like the “mystical-type experience” proffered by psilocybin therapists, the most desirable of highs.

Unlike Edgar Mitchell, the astronaut who claimed to have experienced savikalpa samadhi on his ride back to earth, Anders himself was no mystic. He was an ardent Cold Warrior and Air Force general who worked in the Nixon administration, and eventually served as CEO of the defense firm General Dynamics. But even he reported his own manner of Overview. Before Apollo 8, Anders was a Catholic, and dutifully took communion before the flight, during which he joined Borman and Lovell in reading the first ten lines of Genesis to the folks back home. In other words, he believed that God created the earth and mankind in His image. But that belief would not survive his cosmic perspective shift. As Anders looked at the earth from the moon, he performed a conceptual run-through of the Charles and Ray Eames short film Powers of Ten (whose original sketch was shot in 1968):

I must say my faith was somewhat undercut as I looked back at the tiny earth. I imagined that if the earth was the size of a golf ball at one lunar distance, at ten lunar distances it was down to a BB, [and] at a hundred lunar distances, where it’s hardly going anywhere in space, it’s like a grain of sand. I got to thinking, is that really the center of the universe?

Having seen the world as a grain of sand, Anders made a seemingly permanent post-Copernican religious shift. But the other shifts that he hoped “Earthrise” might engender proved much less lasting. Even though Vaughan-Lee’s film is accessibly if sensitively middle-of-the-road, the almost bitter disappointment of these three old men is palpable. The Apollo program, they realize, did not really raise global consciousness, did not bring about the “interlocking view” that the astronauts had glimpsed. Anders himself, whose career wound up impacting the space program far more than any other astronaut, grew disenchanted with NASA. In later years he vehemently opposed the idea that nation-states should send people back to the moon or to Mars. “Why don’t we get our act together here on earth first and go to Mars as human beings?” he says in the film.

Here we should pause the usual cynicism about Western overlords wanting global peace on their terms. For Lovell, Buckminster Fuller’s idea of Spaceship Earth was not some fanciful piece of design science, or a code for Western domination, but an existential reality. The Earth was a spacecraft, he saw, and we were all astronauts, “whether we like it or not.” And as a participant in a remarkable and successful feat of science, engineering, and logistical coordination, Lovell knew what it meant to work together as a team towards an absurdly challenging goal. But the old man in “Earthrise” knows that we have not rolled up our sleeves.

That’s the thing about the real Overview Effect, the thing that the virtual reality goggles are unlikely to catalyze: the vision affords not just wonder, but also responsibility, and more than a little bit of dread. Borman, who called the crew “unlikely poets” when he spoke before Congress in 1969, may have said it best when he reflected on his own “very very sobering” experience in space: “to see this beautiful little blue marble in the middle of all that darkness and to realize how lonely we really are on this wonderful earth.”

Appearances

I was in Europe for seven weeks, the last three in Amsterdam, where I co-taught a summer course called “The Psychedelic Universe” at the University of Amsterdam with my friend and colleague Christian Greer. The goal of the intensive — ten days of sessions in the morning and early afternoon — was to push back against the often banal medicalization of today by telling the long story of psychedelics through a variety of anthropological, cultural, and mytho-poetic approaches. High points included a guest lecture by the Dutch blotter maker Ed Visser, who I discuss in Blotter, as well as a field trip to Kokopelli, Amsterdam’s most lovely, comprehensive, and sane smart shop. Classroom interaction was rich, smart fun was had, and we inspired at least one student, Anna Formilan, to make a poster about the class.

In other news, Blotter continues to be very well received and will probably be reprinted before the year is out. If you have missed my presentations and book talks, Harvard’s Center for the Study of World Religion has released a video of my book talk there. I’ve done a number of interviews, including one for Jane Hu at The Microdose, the newsletter of the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics. One of the most thorough chats was with Kate Wolf over at the LARB Radio Hour.

Upcoming Events

• This Friday, July 12th, starting at 7pm, I will be joining Sam Stern at the Berkeley Alembic to explore and discuss the dizzying topic of Altered States at Esalen. Sam runs the “Voices of Esalen” podcast, and has been doing a bunch of fascinating (and not always flattering) historical research on the Institute and its profoundly influential (and sometimes profoundly strange) explorations of good old human potential. After presenting some rare archival material, and discussing Esalen tripsters like Stan Grof, John Lilly, Terence McKenna and Rick Doblin, Sam and I will be diving in deep.

• Speaking of Esalen: If you are itching to spend five days on the dizzying and gorgeous edge of the Big Sur landmass, exploring the dynamic links between writing and the spiritual life, your opportunity is coming up pronto. July 15-19, Sravana Borkataky-Varma and I will be offering “Embodied Writing and Spiritual Practice.” In addition to being a good friend and colleague, Sravana is an initiate in and scholar of South Asian Tantra, and has a very dynamic and accessible teaching style. I handle more of the writing stuff. We cooked up this seminar in 2023, and this year even more folks are piling on, so much so that Esalen just bumped us to a larger room. So come on down!

• Two more Blotter book events are coming up, probably the last for the season. I will be presenting the book and talking with Mark McCloud at the Chambers Project in Grass Valley on Tuesday, July 23rd, at the early hour of 6:00 pm; details here. Mark and I will similarly descend on the Booksmith in the Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco, on Thursday, July 25th, at 7pm; more info. Both should be great opportunities to get John Hancocks from the two of us.

Links

I don’t add a lot of random links to these mailers, usually because they are long enough as is, but I cannot resist letting you know about one of the most moving and intellectually rich talks I have heard in a very long time: novelist and essayist Jonathan Lethem’s philosophically provocative and deeply humanistic keynote address to the 2024 Philip K. Dick Festival in Fort Morgan, Colorado, which I was very sad to miss. Admittedly you kinda need to be on the PKD bus to follow all the ins and outs on this one, which ties together current events, Sci-Fi crit, Dickean utopias, self-rationalizing elites, and the sort of ontological pluralism that also informs my book High Weirdness. In appropriate PKD fashion, it’s rather scrappy: Jonathan is wearing an Aerosmith t-shirt and sitting in front of his laptop on a porch, and his riffs are regularly interrupted by the not-so-distant sound of ATVs or motorbikes, buzzing and rumbling like some presidential Mad Max motorcade breaking into our provisional reality, which must surely be a fantasy. Right? Right?

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. If you want to support my work, you are encouraged to consider a paid subscription, though for now I will not be offering any subscriber-only content. You can also support the publication by forwarding Burning Shore to friends and colleagues, or by dropping an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

That's why its interesting to hear these characters reflect in their dotage. Of course that is the time for sentiment and revision, especially from the Cold Warrior Borman, but it is still instructive and illuminating to hear. And that's what modernity does: sacred and profane juxtapositions that leave you hanging.

I see him! He looks...confused.