The View from the Mast-head

Pantheism and its Discontents

I am confused and demoralized and unnerved right now so I kind of want to hide under a rock, but I am pretty sure that the heavy vibes radiate all the way down to the mantle. So instead it is back to Sisyphus the scribbler, huffing up that Substack hill one more time, hoping to gain a perspective worth sharing, or liking, or at least flashing brightly but briefly like an old-school Speed Graphic camera as we collectively clamber through the ring ropes and take on, from the other corner, Madame Polly Crisis — heavily favored, ‘natch — in a WWE bout for which we are absolutely unprepared.

Stamina is important in times like these, and nourishment, and a sense of coming from the core. One of my “hacks”, which is inefficient and vaguely pretentious so probably best avoided by those looking for hacks, is to read heavy works of great literature. This is not exactly an unheard of notion. Stuff I read on the Internet suggests that ploughing through grim fatties by (mostly) dead white guys is enough of a thing already to be officially deemed insincere and performative, a bro flex along the lines of NBA prediction contracts or Orthodox conversion. But fuck you Stuff I Read on the Internet! Stretching my humanities-trained brain and corralling my flagging attention with Harold Bloom deep cuts offers ballast in the midst of the digital deluge. The classics, even the pulpy ones, also provide an opportunity to pull back from the immediacy of panic media enough to recognize the long arc of causes and conditions that feed so much of our current turbulence. After all, the literature of the old ones really has the capacity to resonate across time, especially when the text in question is, like the time in question, apocalyptic.

It’s the power of those resonances that help explain why JF Martel and I are having such a blast teaching Moby-Dick over at the Weirdosphere, and why so many fellow readers there seem to be having a good time as well. Melville’s dense, long, and multi-perspectival Great Book is notoriously grim and metaphysical, but it’s also full of gallows humor, proto-ecological naturalism, cosmic horror, and catalytic prose. In addition, the story seems profoundly relevant at this moment: a tragedy of American extractivism, and of myth-sized payback from beasts exploited in a savage run-through of the petroleum economy that was, in 1851, just around the corner. The novel’s political poles are also familiar, split between a scruffy democratic pluralism and a spiteful and lawless overlord who has left his responsibilities – not to mention conventional economic reckoning – behind. Ahab and Trump are both vengeful, rude, and egotistical old men, great at manipulating toadies and crowds from out of their violent inner voids. Though Melville’s captain is too monomaniacal and ascetic to pave the way directly for Trump, the two titans certainly rhyme.

All this I expected before embarking on my third pass through the novel. What surprised me this time is how deeply Moby-Dick’s visionary passages and ironic paradoxes addressed the vexed journey of expanded consciousness, and whether or not we consider such transformations in “spiritual” terms. Writing to Hawthorne, Melville loosely compared his book to a gospel, while later describing it as a wicked book, with a demonic motto to boot: Ego non baptizo te in nomine patris, sed in nomine diaboli! Elsewhere he notes that things look infernal or angelic depending on your mood, and the perspective moods breed. This multi-perspectival mood both resonates with and resists the vast panoramic expanse of mind suggested by the Transcendentalism of Melville’s day, that new American pantheism that figures like Emerson and Thoreau were articulating in largely optimistic and liberating terms. For even as Melville tastes the power and beauty of the pantheistic vision at various times throughout Moby-Dick, he also critiques and even mocks Transcendentalist exuberance. Instead, he weaves his peak experiences into an almost tantric tapestry of tragic naturalism, offering a tangled counter-vision that does not deny unity consciousness, but re-embeds it into a messy, material, deeply weird world.

The vexed journey of expanded consciousness animates one of my favorite early chapters of the Whale, “The Mast Head.” Ishmael, the unfixed narrator of the novel, who both is and is not Melville, is an ironic seeker of sorts. A lover of arcane lore and exotic scenes, and a broke-ass moody drifter to boot, Ishmael might be the first hipster in American literature. In this chapter, he admits how many young men like him, romantic and melancholy, are drawn to the whale fishery, and how they invariably fail at one of the core tasks they are invariably tasked with, which is to climb up to the mast-heads to look for whales. As is usual with Ishmael/Melville, the chapter begins with a trawl through the archives, wherein we discover early precedent for “standers on mast-heads” among the Egyptians with their pyramids, seen as more solid and worthy than the unsuccessful builders of Babel’s tower. The author also invokes St. Simeon Stylites, a fifth-century Christian hermit who spent his days atop a pillar — see Buñuel’s funny and surreal film, Simon of the Desert — as well as more recent political and military heroes who to this day stare off into the smoggy faraway from atop their urban monuments.

The challenge for Ishmael and his fellow hepcats is the inflationary powers of that wide expanse before them. “There you stand, a hundred feet above the silent decks, striding along the deep, as if the masts were gigantic stilts, while beneath you and between your legs, as it were, swim the hugest monsters of the sea, even as ships once sailed between the boots of the famous Colossus at old Rhodes.” Notice how Ishmael’s body itself begins to expand and change scale, as drug-takers and meditators sometimes report, its mutation allowing it to viscerally match its increasingly more-than-human perspective. “There you stand, lost in the infinite series of the sea, with nothing ruffled but the waves.” But this chillax panorama is precarious as well. There are no comfy crow’s nests up there on Pacific whalers, nothing more than two thin parallel spars called cross-trees. “Here, tossed about by the sea, the beginner feels about as cosy as he would standing on a bull’s horns.” It’s a trick, and a dangerous one.

Upcoming Event:

Learning from the Living World, with Kathleen Harrison, Meghan Walla-Murphy, and Erik Davis

On Wednesday, February 25, at 7pm, I will be hosting Kathleen Harrison and Meghan Wally-Murphy at the Berkeley Alembic for a discussion about deep learning from our spirited world. Whether in the form of animals, or plants, or ancestors, beings from outside our supposedly disenchanted world are leaning in with tales to tell, challenges to mount, and wisdom to offer. Kat Harrison is an independent scholar and teacher of ethnobotany, and the co-founder of Botanical Dimensions. Meghan Walla-Murphy has dedicated her life to wildlife tracking, and understanding how Traditional Ecological Knowledge can serve as a bridge between mainstream environmentalism and the rich world of animism. More information here.

The view from the mast-head is enough to spin anybody’s head, but the expanse proves particularly seductive to a “sunken-eyed young Platonist” like Ishmael, who has the “problem of the universe” whirling in his skull. The mention of Plato here is, like all allusions in this hyperlinked Wikipedic text, hardly accidental, since the type of peak experience catalyzed by the mast-head vision lobs the principles of philosophical idealism into the soul’s felt sense, which Melville communicates with almost psychoactive prose:

[L]ulled into such an opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious reverie is this absent-minded youth by the blending cadence of waves with thoughts, that at last he loses his identity; takes the mystic ocean at his feet for the visible image of that deep, blue, bottomless soul, pervading mankind and nature; and every strange, half-seen, gliding, beautiful thing that eludes him; every dimly-discovered, uprising fin of some undiscernible form, seems to him the embodiment of those elusive thoughts that only people the soul by continually flitting through it. In this enchanted mood, thy spirit ebbs away to whence it came; becomes diffused through time and space;…forming at last a part of every shore the round globe over.

Though Melville was only modestly familiar with Emerson when he wrote Moby-Dick, having perused a few of his essays and seen the Transcendentalist lecture in Boston, Ishmael’s mast-head grok here accords with the idea of the “Over-soul” that Emerson, influenced by Neoplatonism as well as Vedanta, elaborates in an essay written a decade before the Whale. In that text, Emerson invokes “that great nature in which we rest, as the earth lies in the soft arms of the atmosphere; that Unity, that Over-soul, within which every man’s particular being is contained and made one with all other; that common heart.”

Here Emerson’s Over-soul vision ties together nature’s high magnitudes of earth and sky with the fused potential fellowship among people in a common heart. After a century and a half of Eastern religion and philosophy in the West, not to mention the convulsive if often cliched tropes of psychedelia’s “mystical” experience, we have grown familiar with this Over-soul stuff, which remains the summum bonum to many in the “spiritual but not religious” box on the form. But in the middle of 19th century America, when the seeds of SBNR were just getting planted in America’s appropriated soil, such a naturalist and impersonal vision spoke to startling new horizons for thought and experience. Startling — and also terribly fragile, even delusional, as Melville makes clear in the remarkable final paragraph of his chapter, when the rug beneath our ecstatic Platonist gets tugged:

There is no life in thee, now, except that rocking life imparted by a gently rolling ship; by her, borrowed from the sea; by the sea, from the inscrutable tides of God. But while this sleep, this dream is on ye, move your foot or hand an inch; slip your hold at all; and your identity comes back in horror. Over Descartian vortices you hover. And perhaps, at mid-day, in the fairest weather, with one half-throttled shriek you drop through that transparent air into the summer sea, no more to rise for ever. Heed it well, ye Pantheists!

With the seasoned voice of one who, as a young man, himself spent time aloft gazing for whales, Melville reminds look-outs of the concrete dangers of succumbing to the dopey haze of reverie. But he is also making a deeper point about ecstatic experience, or at least the sort of pantheistic “unity consciousness” that formed one of the ideals of Transcendentalism, not to mention today’s more mystic-minded psychedelic scientists. Recall Emerson’s famously trippy flash in “Nature” (1836):

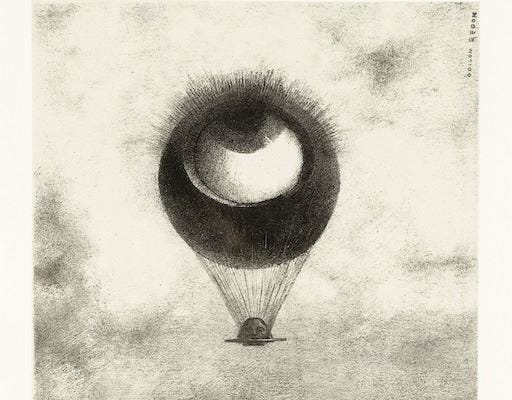

Standing on the bare ground — my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space — all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent Eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.

With the dark ironic turn at the end “The Mast-head,” Melville seems to pluck the “transparent eyeball” out of Emerson’s skull and hurl it deep into Walden pond. What’s going on here? A simplistic view common to Melville critics sees him as a mocking anti-Transcendentalist, devoted to skeptically skewering the Over-soul faith, which here, again, seems more a reverie than a revelation: it is a trance, a dream, a vast field of awareness that is also a lapse. As every beach blanket dozer knows, the ocean can induce lethargic, sun-crisped, liminal fuzz — something that Walt Whitman reminds us only a few years after Moby-Dick’s publication when, in Leaves of Grass, he languidly invites the sea to “rock me in billowy drouse.”

But for Melville the Over-soul trance is not just a delusional dream, and that’s what makes his take poignant and important given our current consciousness culture, a time of jhana tech, hardcore dharma, and democratized 5-MEO meltdowns of space-time. Writing to Nathaniel Hawthorne the summer he was finishing Moby-Dick, Melville again seems to mock the sort of pantheistic ideals which he finds, this time, in Goethe, who suggests that we should Live in the all and merge with the flowers and woods and planets. “What nonsense! Here is a fellow with a raging toothache. ‘My dear boy,’ Goethe says to him, ‘you are sorely afflicted with that tooth; but you must live in the all, and then you will be happy!’” The body that feels pain, that slips on the cross-trees, keeps the score; the rest is spiritual bypass. But later in the same letter, Melville admits to an experience that so many of us have shared, especially when bemushroomed in field or forest:

This “all” feeling, though, there is some truth in. You must often have felt it, lying on the grass on a warm summer’s day. Your legs seem to send out shoots into the earth. Your hair feels like leaves upon your head. This is the all feeling. But what plays the mischief with the truth is that men will insist upon the universal application of a temporary feeling or opinion.

We’ll return to that last qualification, but note first that the All feeling is not just a feeling but has “some truth” in it. Many (but not all) of the extraordinary experiences of expanded consciousness in Moby-Dick mix truth into these pantheistic mergings, especially, it seems, when they involved his fellow man — and I do mean man. Later that same year, Melville wrote Hawthorne again, discussing the gush he felt for Hawthorne upon reading a letter from his friend.

I felt pantheistic then — your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God’s. . . . Ineffable socialities are in me…It is a strange feeling — no hopefulness is in it, no despair. Content — that is it; and irresponsibility; but without licentious inclination. I speak now of my profoundest sense of being, not of an incidental feeling….I feel that the Godhead is broken up like the bread at the Supper, and that we are the pieces. Hence this infinite fraternity of feeling . . . The divine magnet is on you, and my magnet responds. Which is the biggest? A foolish question — they are One.

Even given all the vagaries of recollected and articulated peak experiences, this is a rich and complex set of feelings: erotic merger, ineffable unity, and a remarkable mode of anarchic equanimity, a stoic coolness enlivened with wild fellow-feeling. Indeed the very complexity of this mix speaks to an underlying authenticity.

So why pull the rug out from under such a peak experience? Why this distrust of the All feeling? What’s wrong with pantheism?

One factor is the fact of transience itself, the impermanence that speaks to both the irony of passing enthusiasms and the realism of the morning after. It’s like the meditation master Jack Kornfield’s great book title: After the Ecstasy, the Laundry. In a later chapter in Moby-Dick, Ishmael has another pantheistic experience while squeezing lumps out of the fresh spermaceti with his fellow sea-grunts, one that resonates with his Hawthorne glimpse of “ineffable socialities.” But the spell does not last, and in its wake he makes a call for the more muted satisfactions of the everyday that, to my ears, speaks to the pragmatism in Melville’s view:

Would that I could keep squeezing that sperm for ever! For now, since by many prolonged, repeated experiences, I have perceived that in all cases man must eventually lower, or at least shift, his conceit of attainable felicity; not placing it anywhere in the intellect or the fancy; but in the wife, the heart, the bed, the table, the saddle, the fire-side, the country. . .

Rather than offering an escape from the conundrum of mortal consciousness, Melville holds that pantheistic unity experiences cash out on the plane of the quotidian, of the ordinary messes and marvels within which we make our way. In this he accords with mature meditative (and psychedelic) wisdom: the long value does not lie in the peak, with its mythopoetic intensities and egoic inflations, but rather in the subsequent art of integration, of coming down with elegance and tact — rather than slipping and falling into the drink. The trap in the pantheistic vision does not lie in the experience itself, which is marvelous and not without truth, but in the temptation to reify it into an abiding idol. As he writes above, “what plays the mischief with the truth is that men will insist upon the universal application of a temporary feeling or opinion.” But we shouldn’t aim for that kind of universal application in our kind of universe.

Moby-Dick is a map of our kind of universe, and like that plural cosmos it is fractured, multi-perspectival, beautiful and horrifying, mythic and material. And all these domains and their inevitable divergences are haunted and deeply entangled with all manner of others: with insects and whales and quadrants and archives. That’s the other reason we cannot be fools for the All, which Melville regularly figures throughout his text as a kind of endless and ongoing weave. We are reminded that the word tantra too means loom or weave, what the old Zen coots called “the ancient brocade.” This is the nondual vision not as a vaporous Vedantic oneness, what Tim Leary mocked as a “custard mush”, but as an endless tantric tangle of ongoing phenomena. “Whither flows the fabric?,” Melville elsewhere asks. “What palace may it deck? Wherefore all these ceaseless toilings?” I don’t know the answers, but I do know the cosmic loom leaves nothing out, even the gap of God whose foot is on the treadle.

The problem with the All feeling then is not the All but the feeling that the All is a simple unity, and that its seething and sometimes lacerating complexity has been smoothed away like the calm surface of shark-infested waters. As my friend Aaron Weiss once told me, “Radical pluralism is closer to nonduality than unity.” The tantric brocade weaves with all the threads, even the most grim and violent and wayward. The problem with unity vision is that it releases the burden of entanglement and disruption that attends the pluraverse we actually inhabit, a burden that, in a theological key, we might call the problem of “evil” — always the last and hardest test of any nondualism worth its salt.

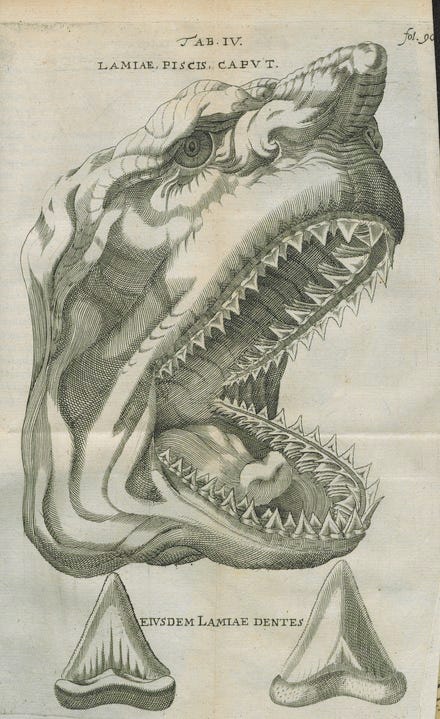

This is a huge conundrum of course, huger even than Moby-Dick, which is one of this theme’s great literary workouts. As was his wont, Melville does not give systematic answers or crystalized conceits but hints and images, and I will leave you with only one clue. Other than in the “The Mast-Head” chapter, the word “Pantheistic” appears only one other time in the book. There it is used to describe the lingering vitality in the body of a dead shark whose jaws are still capable of snapping your hand off. “It was unsafe to meddle with the corpses and ghosts of these creatures,” Melville tells us. Heed it well, ye Extractivists!

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. More than anything, I want to resonate with readers. If you would like to show support, the best thing is to subscribe and to forward my posts to friends or colleagues. You are also welcome to consider a paid subscription, and you can always drop an appreciation in my Tip Jar.

What's the comment version of a standing ovation, because that's what I want to put here.

Thanks a million for this. I'm not able to participate in the Moby-Dick program you're running right now, which is too bad because it is my favorite book (whatever that means).

I'm always heartened when I find people who have read it and seen it for what it is: the strangest, funniest, scariest, most esoteric, most twisted, most head-spinning, Weirdest book in English that I know of. It is Weirder than Finnegans Wake, in its way, and I'm currently in a Wake reading group. Oh, and it's a good adventure story. The second time I read it was during a period of great demoralization leading up to and including the election of Trump I, and I couldn't believe how relevant it was. But to read it as an allegory for current events, however useful, reduces it. Besides, that's what a work of prophecy is, right? A work that is always relevant.