Up Up and Away

Intrusive Fictions

You can always blame it on the drugs, or the science fiction — both of which laid down their otherworldly templates early in my budding brain — but occasionally I slip into a whole other world. I mean this in the most prosaic way possible: with little or no intoxicants in the system, when the sunlight or the peptides or the morphogenetic fields are just right, I swerve into what feels like another ontological realm — a surreal parallel track that runs like a shadow groove alongside the ordinary everyday.

One early groove-slip happened in New Haven in the 1980s. I woke up unusually late, sludgy with hangover, and rather than caffeinate at home I threw on jeans and a t-shirt and headed down to Claire’s Corner Copia for breakfast. It was a spring morning, bright but still crisp, and when murk-headed me hit Chapel Street, a modest commercial thoroughfare that abutted the Yale campus, I walked into an R. Crumb cartoon.

I mean this literally, although what it means to literally find oneself in an exaggerated representation is a conundrum even the deconstructive literary sass I was cultivating at the time could not handle. It was a rude marvel: the power lines hung thick and heavy, the pavement unrolled cracked and soiled, and the passersby kept on trucking with that inimitable Fleischer-esque bottom-heavy gait, their shoes distended like balloons, their pants markedly and unfashionably flared. Even the kempt folks headed to work seemed scruffy, oddly swollen, torn and frayed. (That’s me on the lower left below, at least that morning.) The trance startled and amazed me, a wondrous WTF, but Crumb’s entropic lines simply beefed up the turbid exhaustion of my hangover rather than offering any escape. Three or four blocks later, I entered Claire’s, the bite of coffee hit my nose, and the Haight Street phantasmagoria dissolved into ether.

An even more uncanny genre slip occurred a couple decades later in San Francisco, a more dreamlike episode that is also harder to grasp in retrospect. I had been to the doctor and, though undrugged, was perhaps a bit rattled from the medical theater. Turning onto Polk Street, I headed for lunch, and somewhere along the way I felt like I was slipping back in time. How exactly this manifested itself I don’t know, but whatever Ubik careen I was on landed solid when I turned into another diner: the legendary Swan Oyster Depot, a narrow lunch counter which in those days did not invariably present a line of tourons down the block.

A San Francisco jewel, Swan is already a bit of time trip, a rare island of workingman’s bonhomie replete with tile floors, old framed photos hung salon style, an ancient cash register, and a pink chaos of fish on ice. My time trance simmered through the whole meal. As I chatted with Jimmy Sancimino — one of the beaming brothers who own the place, his white apron crisp and friendly as heaven — the radio was playing ‘30s jazz, and Jimmy took a phone call on an old dial-up. As I mopped up my Crab Louie, suspended in my weird, it dawned on me: I hadn’t slipped back in time so much as entered a David Lynch domain where some ominous oddity lurked just beneath the surface of cheery American corn. In other words, the feeling was less alt-history hiccup than a fictional drift.

What’s happening in these moments? In his great essay on faery stories, Tolkien argued that the genre of fantasy is in part a response to desire, and that the momentary intrusion of such fictional otherworlds might represent, like Freud’s dreamwork, a temporary and virtual realization of our wants — even if the fantastic world is, as in my Crumb vision, not particularly joyful. But I suspect something else is going on, something involving how cognition represents its own workings to itself. According to the increasingly dominant neuroscience model of the predictive brain, our nervous system is actually fabulating all the time, constrained by sensory signals and the quality of our reality-testing and bias revisions. In this model, the unfolding of an apparent “fiction” on the platform of lived experience is, paradoxically, closer to the neural truth than the usual realism of the quotidian.

One more example, milder and more relatable. Walking into our corner store in 2003, I saw the Chronicle headline announcing Arnold Schwarzenegger’s election as the Republican governor of California following the recall of poor sad Gray Davis. (No uncanny deja vu here!) I wasn’t happy about Ahnold, though like many coastal Californians I now fondly recall his reasonable, socially liberal conservatism as a lost golden age. But the headline still kicked me through a PhilDickean portal into a parallel world where a rictus-grinned, outrageously muscled Hollywood cyborg with a telegenic media wife had taken over the state government, a kind of Palmer Eldritch-meets-Radio Free Albemuth scenario. That this state of affairs was nearly the actual case only intensified the sense that I had, like the dude in They Live, briefly looked through the dark lens of absurdist science fiction and seen the truth.

I suspect most of us have been experiencing these “Sci-Fi headline” moments a lot in recent years, so much so that, in my experience anyway, even the vertigo of the slip has become familiar. You scan your newsfeed, the start of another ordinary day, and you read that Coors is injecting advertisements into people’s dreams, or that a new neuroprosthetic helped a stroke victim immediately translate his neural signals into complete words, or that a billionaire, having beat another billionaire into outer space, invites you along for the ride. And it’s all kind of whatever, another shock to a benumbed soul, another hallucinogenic wrinkle in the new normal, familiar in its unfamiliar mix of wonder, dread, and wooziness. Unusual business as usual, just like a character at home in her weird story-world.

But that felt sense of fictionality is key I suspect. There may be an even deeper connection between the crisis of truth (“fake news,” Q drops, and all the rest) and the aggressive rate of technohistorical development and hypermedia than we usually imagine. It’s not that we sense “SciFi” because the real world is catching up with our speculations; it’s that the collision course between accelerating technical novelty and our stressed bubbles of consciousness makes the immediate sense of reality itself feel fictional. It’s not that cold, hard reality disappears, but that it becomes just another genre. One that, like all the others, is spliced and diced, mocked and massaged, as the ordinary operations of media, advertisement, politics, and power give way to a surreal blur without relief.

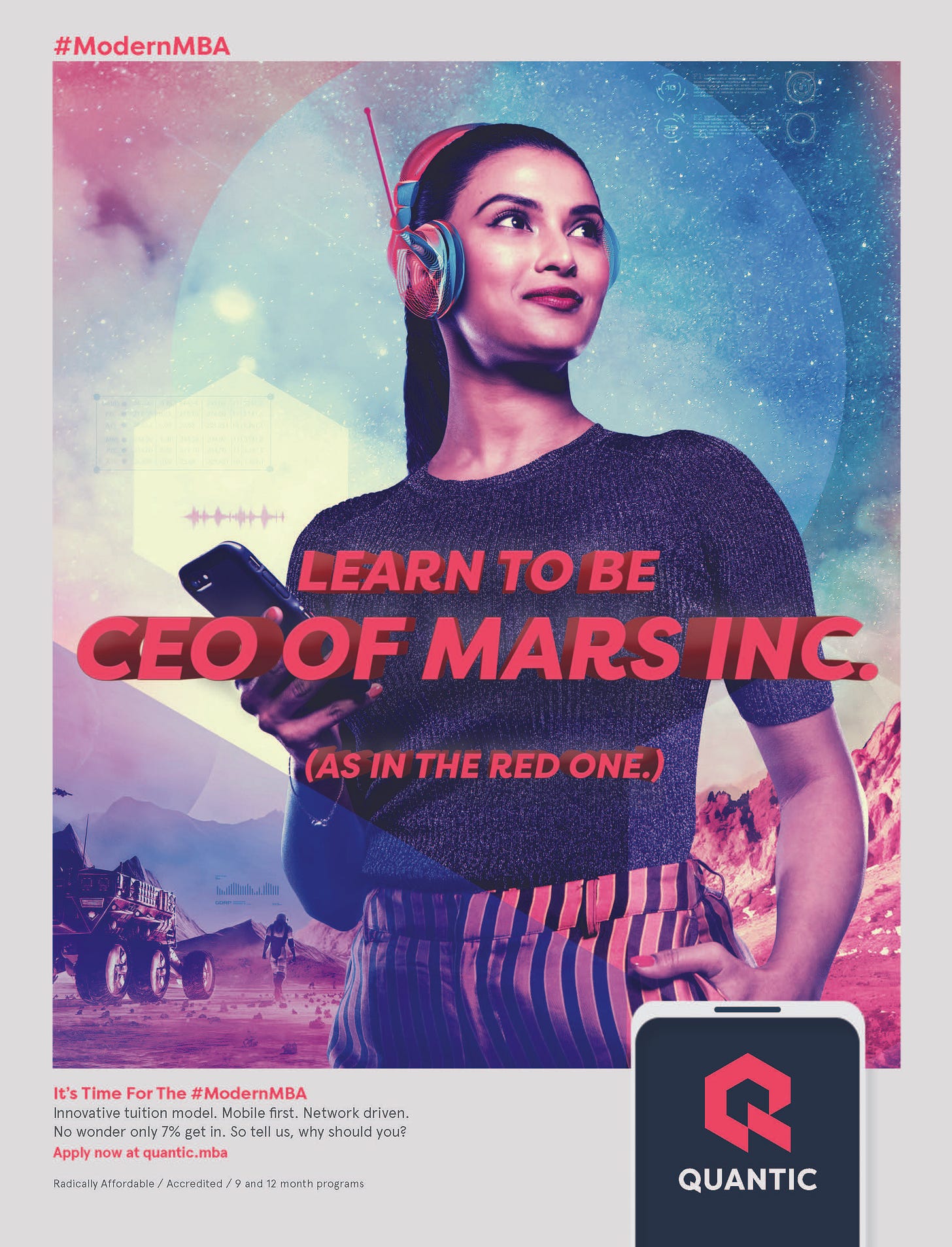

Which brings me, at last, to my most recent Sci-Fi flash, one that thematized — as the deconstructive Yalie me would have said — this very blur. Compared to the heavy hitters above, it wasn’t that big a deal. With a head full of sativa, my eyes fell upon an advertisement in the latest issue of The Economist, a magazine I read partly for the reliable frisson it provides between level-headed rationality, with its stats and “keep calm and carry on” tone, and the pathological symptomatology of an unraveling global dystopia. Here’s the ad:

As you can tell, Quantic is an MBA program that you can suffer through on your phone, which is networked with other phones, which I guess makes the whole operation futuristic, as does the “innovative tuition model” it offers, seemingly designed to open the doors to a broader demographic range of prospective entrepreneurs who must, nonetheless, still play the meritocracy game. “Do you have what it takes?”

I’m not sure how novel all this is, but the trendy creative agency Admirable Devil has wrapped the program in a slick, adventurous, hedonistic fantasy pitched towards younger millennials and Gen Z: outer space, rockets, New Age orbs, and, well, cybersex. I mean, look at that outfit! With her cocked hip and kinky one-piece — whose high collar adds just the right tone of la décadence — this MBA babe radiates an air of pleasurable power as ready for Berlin’s KitKatClub as for networked boardrooms of the future.

That babe’s image rang a bell. Leafing through other issues of the magazine, I found an earlier ad that features the same woman, the same image actually, but alone this time, striking her pose against a purple planetscape of extraterrestrial rovers and astronauts, with Jupiter and Saturn hanging above pendent as D cups. The tag reads “Make Your Moonshot Less of a Long Shot.” “Moonshot” is lame bizspeak, of course, of a piece with “tiger team,” “blue sky thinking,” and the verbs “to sunset” and “to dogfood.” But the ad literalizes the tired moonshot metaphor in a way that suggests that the tedium of business culture can be transcended if we can just expand that culture into outer space.

In both images, this woman radiates an attractive aura of self-pleasure and self-possession, a reminder that on top of its intellectual challenges, its competitive efforts, and the immense personal sacrifice required, making real money can also be hot. But it’s the two fellows flanking her in the 2099 ad that really take the mooncake. Though their non-SciFi video ads mock typical MBA bros, Quantic here lets us know that white dudes still have a place in the future. Though clearly the least energetic figure, he has a smug haircut and a high-collared jacket that suggests he maintains elite status. That said, his jacket is not made out of vinyl, and he is not interacting with, or getting, the babe. That’s OK though, because whether or not he even wants the babe — I can’t tell, the millennial codes for masculinity often read fluid to me — he has sublimated his aspirations into the erect rocket that looms behind him. By identifying with the apparatus of exploration and conquest, he is promised a kind of transcendence even if he does not get the goods.

It’s a different story with the black guy. I am not sure how to interpret all the visual codes here, but they are worth enumerating: he’s wearing a T-shirt rather than a high-collared jacket; he is the only one not looking at us; and he is flashing a toothy, shit-eating grin while they are merely smiling. Also a strange, possibly mystical orb hovers above his head, as if to suggest that the angels and aliens and lens flares are united behind the idea that his time has come. Ms. Moonshot may just give him a shot as well.

Of course we are not meant to take any of this seriously (I almost wrote “siriusly”). After all, the idea that human beings will have much to smile about in 2099 is already a stretch. (Maybe the AIs are making them do it.) On a normal night I would have read the goofy code right and just passed these images by with no more than a whiff of distracted bemusement. But with all the cannabis in my system that evening, the salience of the thing became amplified into an allegorical clarion. My brain steam-rolled over the irony padding this ad and smashed straight into a revelation of things to come that are already here.

Such over-reading is one of the ambivalent gifts of cannabis — great for turning up the significance volume, especially on elliptical or mediocre media, but dodgy in its tendencies towards paranoia and delusion. In my case, the Quantic ad did not incarnate a prophecy of our actual future, but rather a premonition of the sorts of advertisements that will appear, without any irony, in that future. In that sense, my Quantic experience totally recalled the Offworld advertisement we confront early in Blade Runner (1984).

The Offworld ad floats over a city where absolutely nobody believes that “a golden land of opportunity and adventure“ awaits them in space. As such, its cheesy, old-school pitch only serves to widen the disjunction between dystopian Los Angeles and whatever aspirational hopes are still capable of seizing the human brainstem at this benighted time in history. Quantic also needs to hurtle its fantasies into the heavens, but once again, its playful and ironic sense of free-floating fabrication only calls up — as in a reverse print — the dystopian lineaments of our present earthly condition, with its anxious crowds, economic instability, and terrible weather. In such a time as ours, only a goofy fictional picture of space exploration fits the bill here, because the bill is to keep reality out of the picture, and to pretend that we don’t desperately need the new generation of movers and shakers to skip the sparkle-pony space dungeon and aim their smarts at our hydra-headed global crises.

Quantic’s fantastic denialism reminds me of another ad in another PKD flick: the televised spot for the memory-manufacturing service Rekall that the future Governator — the synchros are coming hot and heavy here — sees in Total Recall (1990).

If you haven’t seen this great bad movie, let’s just say that things in Total Recall are not as they appear, including Mars, which serves as the central simulacrum of the film. And this in turn dovetails nicely with a Quantic advertisement that ran in The Economist a week or two before the kinkier ones discussed above.

Like the earlier moonshot, Mars Inc. signifies all the delicious and fantastical career opportunities that still remain in that mythic land of “the future.” That said, this more down-to-earth MBA babe is presumably not herself on Mars, where her exposed skin would freeze and shatter in about three minutes. What links her to the Great Beyond, instead, is digital technology: the groovy Beats-style headphones, accessorized with antenna, and her mighty mobile, which we can see is receiving the signals that hover over the device. Graphically, the human here is associated with circles: the headphone’s cans, the model’s round head and chipmunk cheeks, and the astral halo behind, which re-centers the action on the human subject amidst all this pop posthumanism. But technology, instantiated metonymically in the phone, is associated instead with a crystal shape that mirrors Quantic’s logo, a reminder that digital technology itself has finally — more lame bizspeak here — “squared the circle.”

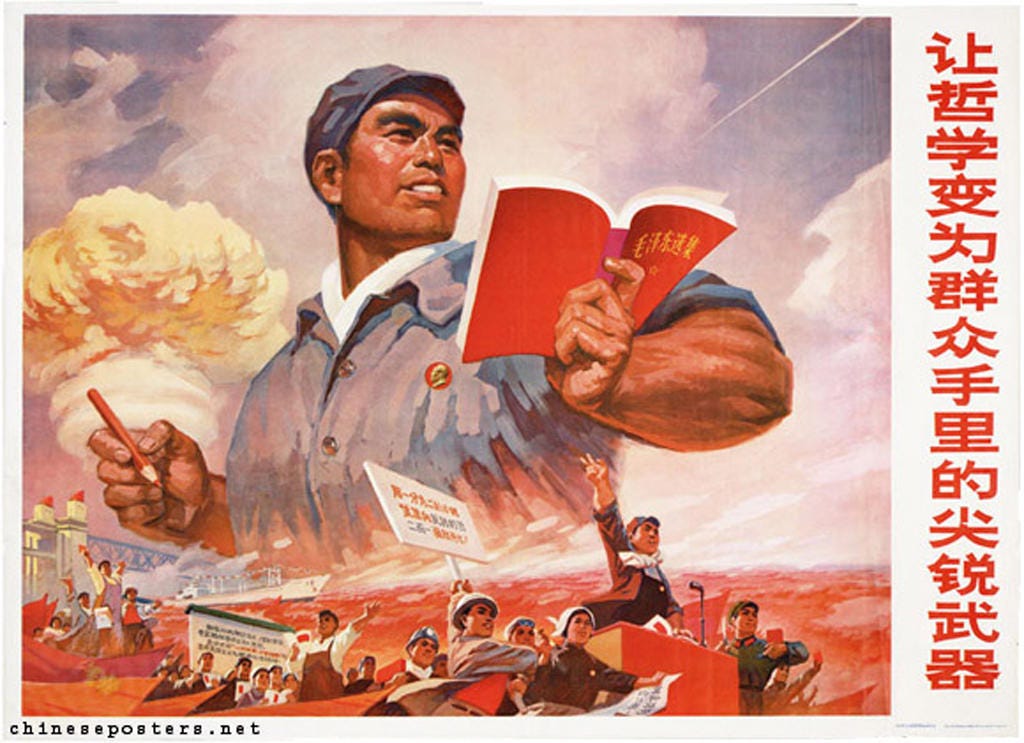

In our actual world, Mars Inc. is a candy and pet food corporation over a century old. That’s the main reason they underscore “the red one” here, as it would be a shame to confuse the young woman’s mobile — a key feature of Quantic’s pitch — with a large chocolate bar. But the phrase also conjures up another red world, one whose visual language lends some uncanny and ironic resonance to this last Quantic image.

Both images represent enthusiastic human bodies channeling historical opportunity, a can-do spirit inspired by a hand-held chunk of media and the visionary possibilities of technological and social change. Both heroes are young, and part of a youth revolution of sorts, one that demands gender parity, and actively divides from the destiny of white Europe. There are significant differences as well of course — while the cultural revolutionary is active and physically dynamic, as comfortable with a pencil as a nuclear device, our MBA is calmly and casually processing data in a largely virtual matrix of advanced digital operations.

A more crucial difference is the fact that the MBA is alone, except for the walking body we see exploring Mars, which might be a telepresent robot for all we know. The contrast between Communist collectivism and the hedonic hyper-individualism targeted in the Quantic campaign is stark. But if this is an intentional echo — and sativa me suspects it is — I think it goes beyond ironic juxtaposition. Some deeper dialectic is afoot. Perhaps history will come to see our modern MBAs as equivalently irrational dupes of a totalizing ideology: the cosmic reign of capital. Or perhaps these frisky space-faring Quantic go-getters will selfishly build the working framework that will then, through some weird AI Aufhebung, realize a Fully Automated Luxury Communism on a Russian Cosmist scale. “A new life awaits you. . .”

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

See you at the pahty, Richter!

I keep thinking about the Robert Crumb end of this spectrum how similar yet even darker it is to the streets of LA in Blade Runner. How Crumb never shows us this slick future fantasy because he. like many of us, never saw it with an entry sign for him, preferring to get behind the scenes at the more accessible peep shows in whatever neighborhood he found himself . I admire Crumb's art but mostly from a distance. Too willing to stare into the darkness in so many eyes. The ads for a bright future continue to roll out of NPR, magazine land, the New Yorker, Forbes the internet,.... even while the pandemic kills, towns flood and fires burn. They have to report it but somehow seem to barely notice the pattern. R Crumb hangs out in a village in France making radio shows from his collection of old records, illustrating the Old Testament and his dreams. I work in my large garden, talk and eat with my partner, teach kids to make things with their hands, paint and fire glass, but cannot keep from the too frequent stare into the future. It isn't dreamy at all, though sativa can sometimes make it seem weirdly funny.