Viral Roots

The Burning Shore, no. 2

For fitful sanity’s sake, I’ve been trying to get outside everyday, which is pretty easy living in temperate San Francisco only a few minutes walk from Golden Gate Park. My wife and I have held on to our rent-controlled Edwardian flat for a golden eternity, so I know the paths and possibilities through the east end of this park pretty well, although I am enough of a creature of habit that I still stumble into novel nooks and crannies now and again. For all its grids, San Francisco is a fractal city, but that’s another story.

GGP is a great place for a proper stroll, though an excess of roads and asphalt paths limits the rustic, expansive sublimities achieved by Brooklyn’s Prospect Park, for my money—but there’s no fee!—the best major city park in the United States. Like Prospect Park, GGP is largely a construct, and a much less likely one as well, having been built—by a 25-year-old engineer no less, this is San Francisco—largely over the sand dunes that originally dominated the desolate western half of the peninsula, known by the weird moniker the Outside Lands. The dominant trees in the park today—eucalyptus, already a naturalized citizen in the late nineteenth century; Monterey Pine; and the witchy, wind-twisted Monterey Cypresses—were chosen in large part because they grew fast with shallow roots. Get it? This is one of the things I love about California: it keeps staging allegories of itself.

This year San Francisco hoped to be celebrating the 150th year of the park, but it is now only remembering it. The jubilant, new, NASA-colored SkyStar Ferris wheel—excuse me, “observation wheel”—stands idly by the Music Concourse like a sad unicorn space scooter drained of peppy VC capital. The Japanese Tea Garden is closed, and the shuttered DeYoung is still announcing the Black Power show whose closing days we visited in March, with much delight, just before the shelter-in-place came down.

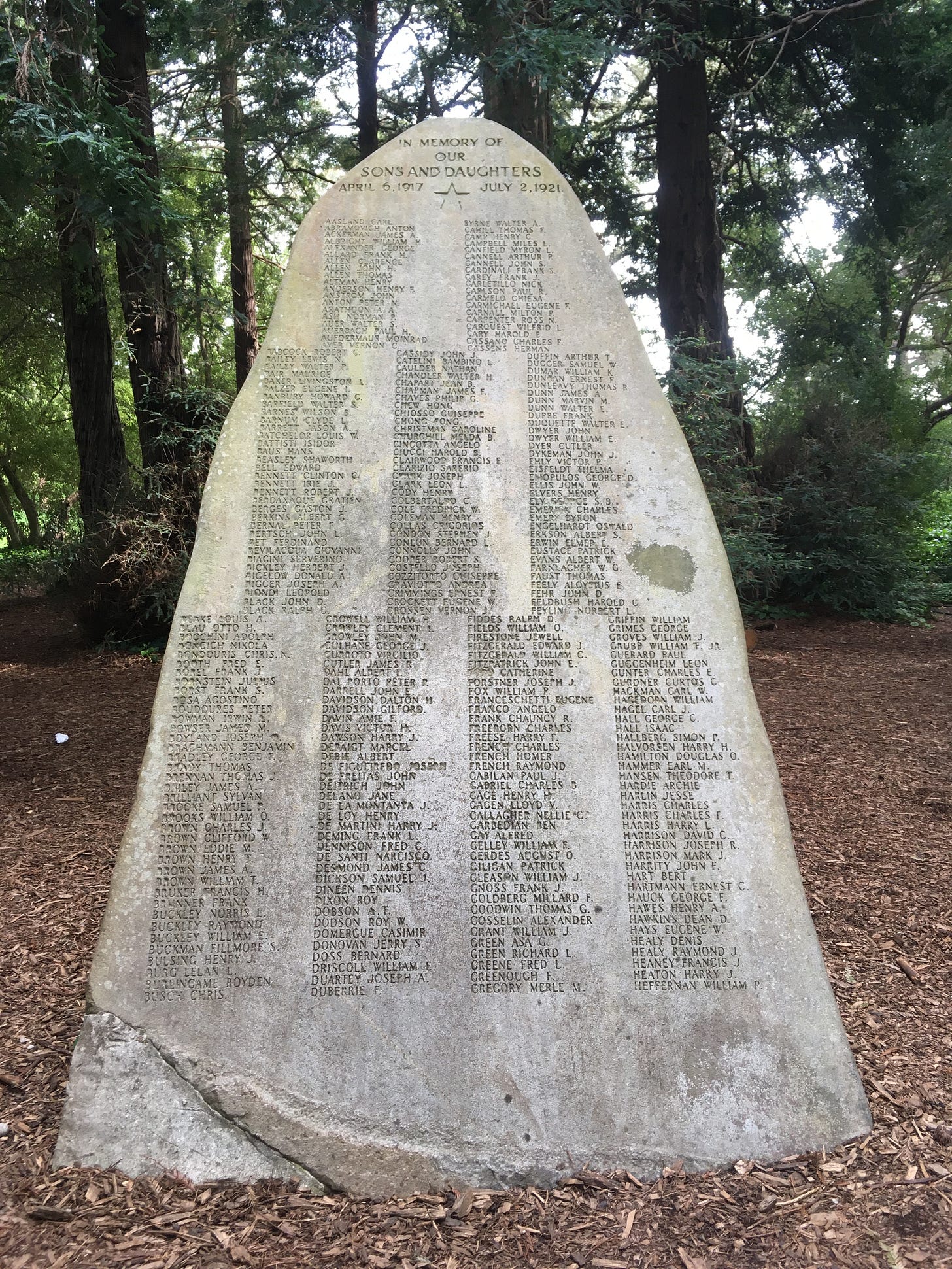

Yesterday, I sauntered through the park with a pal, and entered the Heroes Grove just to the north of the DeYoung’s observation tower. I wanted to visit the Gold Star Mothers Rock, an oddly oblong and sorta naturalistically carved memorial for San Francisco’s World War I dead, set beneath coastal redwoods throwing their hushed shade.

Because we were talking corona politics, I wanted to show my pal one particular and somewhat peculiar name: Inyo Atherton Russ, who happens to be, or to have been, my great-great uncle. His family name is my middle name, and it belongs to one of the earliest established San Francisco clans. Downtown building buffs would recognize the name from the modernist gothic Russ Building on Montgomery Street, where the Russes nailed together their first ramshackle home out of the gutted remains of the schooner that pulled them into Yerba Buena in the lucky year of 1847. Expect more on these old ghosts in later posts.

Inyo’s given name derives, in classic romantic-settler colonialist style, after a misunderstood Native American word (Inyo did not originally name the mountain range in Inyo County, nor the “dwelling place of the great spirit” as claimed by dew-eyed etymologists on the Internet, but to a Shoshone dude named, well, Inyo), my enlisted ancestor died toward the end of the war, in July 1918, in the U.S. Naval Base Hospital No. 5 in Brest, France. He did not die of the wounds that probably brought him to that port town, which lies on a bay near the cliff-cut westernmost point of the continent, and so hopefully reminded him of home. He died of the Spanish flu.

Inyo’s sister, Linda Russ, my great-grandmother, died of the virus the following January. She was part of the second wave of infections that exploded following San Francisco’s choice to loosen social restrictions that previous November. (How’s that for a century loop?) Linda had only recently given birth to my grandmother, who was then passed on to her grandmother, who agreed to raise the child only if the widowed father agreed he would never try and take her back.

After my wife and I moved into our current pad in Cole Valley, many years ago, we discovered that the pair had lived only a few blocks away from us, on Belvedere. My grandmother attended nearby Grattan Elementary, slurped chocolate malts on the Haight, and learned to drive stick on the Thiebaud-worthy inclines of 17th Street. For me, such psychogeographical reverb is part of the magic of history, but it also reflects the more peculiar condition of having roots in a rootless place. The already uncanny layers of echo and return carried by our ancestors twist weird and synchronistic in an environment that relentlessly throws itself into novelty, self re-invention, and historical amnesia. Even the bones of the older Russes were moved to Colma over a century ago.

I’ve swung by the Gold Star memorial many times, just as I often walk by my grandmother’s childhood home. Part of what it means to explore the world for me is to stalk the spectral resonances scattered through time. But I wasn’t ready for the power of my recent encounter with Inyo, and by echo with the older sibling who partly passed on her flesh to me. This day it was as if the inscription on the stone had grown claws, as if the vaguest of traces were amplified by the ambient shitstorm of today’s anxiety, fear, and rumor into a sharp, devastating flash: this is what it is to die young in a pandemic, lonely amidst so many also undone, buried in hospital shrouds and gummy lungs, grieving a home you won’t see or a baby you will not raise.

One of the ongoing shocks of Covid-19 is simply how shocking it all is, even though, probability-wise, we should not be surprised about a raging, mutant, global virus popping out of the fraught interface between humanity and the wild. But for some reason, we are more imaginatively comfortable forecasting far less likely catastrophes. Perhaps there is something essentially out of joint about pandemics, an archaic indistinction, not quite outside of history but hostile to its work. Pop memory recalls World War I, as well as the silent stars and sexy bobs of the Roaring 20’s. But the Spanish flu? Lotsa people I talked to a few months ago hadn’t even heard of it. It just didn’t quite fit the story. But now we are here and they are back, the ghosts of pandemic past.

—Erik Davis

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of the Burning Shore. Over the next few months, I will be experimenting with various types (and rates) of content, and will eventually create subscriber-only content. Please consider subscribing now if you can.