In this post I riff on re-watching Apocalypse Now Redux in the lingering shadows of 9/11, and find that it resonates with many of the concerns that fuel the Burning Shore. But first, a few announcements. As always, it may be more pleasant to read in your browser; just click the title and you are there. — Erik

Upcoming Events

(•) The Dharmanaut Circle

Last month, the first gathering of the new Dharmanaut Circle took place on Zoom. Picking up where the San Francisco Psychedelic Sangha left off, the Circle is a monthly online meditation and conversation space for Buddhist psychonauts, experimental yogis, and mutant visionaries who dig my style. We took on peer-to-peer spirituality and the idea of seeker self-reliance, enjoyed a guided meditation through the senses, and closed with a rich Q&A. Switching to the first Sunday night of the month seemed to do wonders for attendance, and I have a really good feeling about the evolving sangha. Follow this link to register for the next circle on Sunday October 3, at 6pm PT. Suggested donation $33.

(•) The Way of the Psychonaut

Earlier that same Sunday, Oct 3, I will be participating in The Way of the Psychonaut, a weekend conference on psychedelia put on by the Pacifica Graduate Institute, where I currently do some teaching. For my panel, which takes place 1:30 pm, I will be leading a conversation about psychedelic religion and spirituality with a dynamite group of thinkers: Belinda Eriacho, Rachael Petersen, Bob Otis, and Dr. Christian Greer (with whom I will be teaching at Harvard next year). More information and tickets here.

Links

(•) Into the Mystic

Last month I did a Zoom webinar with two smart fellas from Watkins Books, London’s oldest shop devoted to occult, mystical, and spiritual literature. I love the place, which invariably overburdens my luggage on the way home, and I love talking High Weirdness with folks already deep into the wayward ways of the esoteric. We conversed about modern mysteries, my writing career, and the challenges of navigating our times with heart and soul intact. Enjoy!

(•) Finders/Keepers

This month the Brooklyn Antiquarian Book Fair will be streaming an interview with yours truly conducted by Brian Chidester, the archivist and SoCal historian behind the marvelous Dharmaland project I wrote about last time. Our conversation, in which Brian and I discuss science fiction, collecting, history, and spiritual scholarship, is part of a riveting “Finders/Keepers” program focused on archivists of pop esoterica. You can listen to our conversation here.

9/11 Redux

The 20th anniversary of 9/11 hit me weird and hard, for reasons both personal and geo-political. Coming so close on the heels of the Taliban’s depressing snatch-back of Afghanistan after a hardly coincidental 20 years of war, the anniversary date only underscored the dreadful expenditure and moral murk of that conflict and the seemingly god-given inevitability of grim jihadist rule. Because the destruction of the Twin Towers is so clearly etched in my memory, and because it occurred relatively long ago, I felt an almost nauseating sense of aimless, murderous repetition stretched across an immense and barren waste of time. This empty lurch resonated with the deep myth that I and many other Americans unconsciously hold, that something happened near the turn of millennium, some archon grab or glitch in the matrix that jumped the tracks of history into a parallel universe that rendered the last decades, for all their sound and fury, strangely listless and insubstantial, like a bubble, or an echo, or a digital magic show that ends with a man dangling like a hanging chad from a retreating American aircraft, not unlike those other men who clung to other aircraft fleeing another morass another few clicks back. Saigon, shit.

We were awoken that September morning twenty years ago by an employee of Jennifer’s, asking if they should come to work. “Why wouldn’t you? What’s the problem?”

“Oh you don’t know. Just turn on the TV.”

And the TV continued to mediate the event throughout the morning and the day, as we hung on the phone with old friends in New York and as I comforted my sometimes weeping wife. The TV also delivered the most uncanny moment of a most uncanny day: a shot of a female reporter, barely holding it together, attempting to communicate the particular horror delivered by the the rain of scorched office materials that fell about her near Battery Park. Reaching down and grabbing a random piece of paper, an invoice if I recall, she held it close to the camera and read out the address. Something fucked up the feed, and the video stuttered, her gesture and words repeating themselves half a dozen times before getting cut off upstream. The media glitch, itself a symptom of an emerging face of power that has now transformed the world, rendered this banal document prophetic, the reporter’s words becoming the mantra that would drive us into so much devastating bullshit: “One World Trade Center / One World Trade Center / One World Trade Center / One World Trade Center / One…”

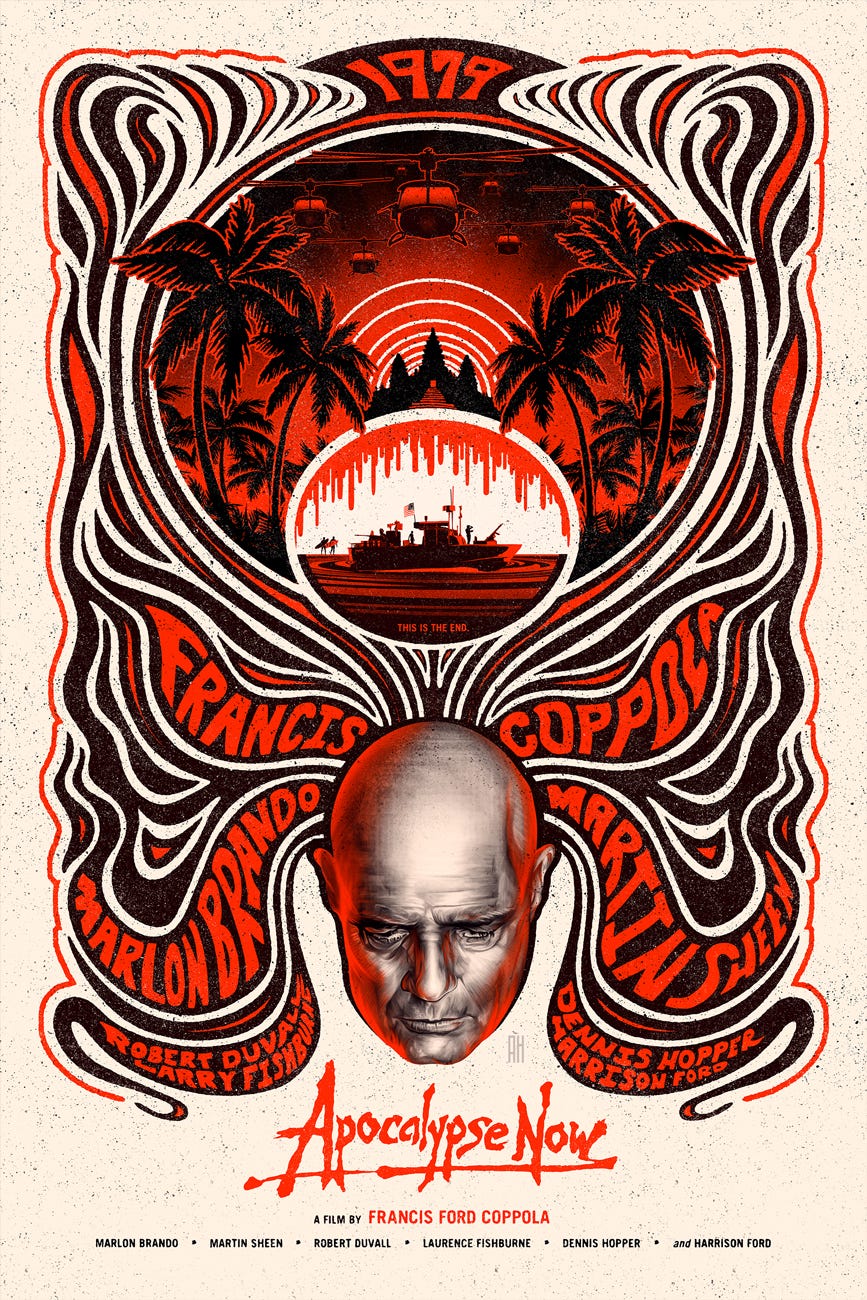

It was a weird and hard day. The thing was, I already had a ticket for a movie that night. Apocalypse Now Redux, Francis Ford Coppola’s just-released too-long director’s cut, was showing at the Presidio down on Chestnut Street in the Marina. It felt vaguely sacrilegious to catch a flick on such a day, but I didn’t mind the break. I wanted to experience the surreal Walter Murch sound-bath in a cinema again, and besides, the title was too synchronistic to beat. I still have the stub somewhere.

I drove down early and sat in my car by the Palace of Fine Arts, listening to the BBC. In that over-clever whistling-through-the-graveyard tone, the anchor introduced a spot exploring “what Americans felt” about the day’s events, which featured interviews with young tourists wandering around London in a daze. I was working as a journalist at the time, which normally would have led me to identify more with the BBC smart-aleck than the corn-fed backpackers he interviewed. But not today. What they said was what I felt, and the wall broke, and I cried and cried.

As for the film, I’m with the Guardian’s Alex Hess: “It’s the supreme achievement of Apocalypse Now that it manages to exist simultaneously as a sublime relic of golden-era film-making and as an utterly ramshackle mess.” B-movie pulp with obsessive editing and sublime sound design, Apocalypse Now may be the ultimate big-budget example of Manny Farber’s “termite art,” whose craftsmen, like Coppola, are “ornery, wasteful, stubbornly self-involved, doing go-for-broke art and not caring what comes of it.” Like Farber’s “termite-tapeworm-fungus-moss art," Apocalypse Now moves forward by “eating its own boundaries, and, like as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity.” Kinda like war in fact.

I first saw the movie on 70mm the month it debuted in 1979. I was 12. My parents had divorced a decade before, and I frequently pressured my dad to take me to R-rated movies on our weekend outings. Already an early ‘70s nut, I was fascinated by Vietnam, and had applied similar pressure to see The Deer Hunter and Coming Home (whose erotics I found puzzling). But Apocalypse Now was something else, a comic-book mythopoetic Gesamtkunstwerk that also prophesied the surreal, druggy, somewhat deranged headspace that lay just around my own personal Southern California corner. After all, Apocalypse Now was the first hardcore war movie that was also a hardcore stoner flick.

My high school crew watched it whenever it showed at the Ken, a midnight movie rep house near downtown. I also saw it a number of times in college, even as I trained myself on more subtle arthouse fair, which was kinda like returning to Physical Graffiti or the DK’s “Holiday in Cambodia” amidst a diet of musique concrète, Ali Akbar Khan, and Miles’ first quintet. So for me it’s not even a matter of taste or superlatives. Like 2001: A Space Odyssey or Performance or Monty Python’s Holy Grail, Apocalypse Now is just stitched into my soul. I’m not interested in declaring it the best American movie of the ‘70s, just as I’m not comfortable declaring the Grateful Dead the mightiest live band of that decade, or Michael Herr’s Dispatches — an important influence on Apocalypse — the era’s most visionary New Journalist reportage. I wouldn’t try to argue these things against a hater or a doubter. But my heart knows them to be true.

So this week, in the lingering shadows of the absent towers, Burning Shore decided to watch the movie again, the first time in twenty years. Some critics think Apocalypse Now Redux, at 202 minutes, is the worst of the three official cuts of the film. I was tempted by Copolla’s recent Final Cut, which trims 14 minutes from the 2001 bloater I last saw, cutting the dumb Playboy bunny romp but keeping the absolutely necessary French plantation sequence, which invites the specters of history into Copolla’s seance, not to mention the felicities of junk, a crucial Nam drug otherwise missing from the film’s pharmacological invocations of acid, alcohol, and the “Buddha time” of cannabis. I definitely was not up for the 289-minute assembly cut that’s floating around, despite all the Doors songs.

We begin already on the high plains of cinema, with the chopper whompwhomp and the junglescape and Jim Morrison channeling “The End” from a Western shore so far out its gone exotic and Eastern. The flames from the silent napalm explosion dissolve into Martin’s Sheen’s hanged man mug, overlaid with a ceiling fan whirling like some dread kalachakra, while flickers of Khmer idols presage the hieratic heart of darkness waiting for us at “the end” of the film.

This bravura opening sequence, as feverish and bold as a Dionysian tragedy or a Kirby comic, introduces the film’s key formal technique, which informs both the editing and, by metaphoric extension, much of Murch’s sound design: superimposition, the palimpsestic layering of images, times, fragments, echoes. Apocalypse Now’s revelations are composed of such overlays — hallucinogenic juxtapositions that unleash symptoms rather than signs, just like surrealist poetry or astrological conjunctions, or the sort of insights that bloom in the tripping mind. Signs are messages from a sender to a receiver, but symptoms open doorways to something murkier, more magical, and more pathological. You are not even sure who is in control anymore, the person (or director) or the pathology. That murk is what spawns the archetypes we latch onto, like the swampy Nung birthing the murderous frog-green Sheen at the end of the film.

The Doors open another one of these hidden portals. On the surface Apocalypse Now is about Vietnam, or the mythopoetics of war. But it is also a symptom of California and its counterculture, and that counterculture’s brief infection of the studio system. It’s always dodgy reading Hollywood films for Californiana, since actors and directors and producers all bathe in the haze of LA, but Coppola and Apocalypse Now have special claim. Coppola was a different kind of Californian for one thing, a Bay Area boho with a Napa ranch and a San Francisco studio, and locals swear he was good to the hippies and punks back in the day. In the film, we see Golden State warriors like Bill Graham, Charlie Manson, and Dennis fucking Hopper, performing the kind of addled visionary freakdom he knew inside-out. Early drafts of the film were named The Psychedelic Soldier until screenwriter John Milius decided to change the title in order to mock a hippy button he saw that read “Nirvana Now.” You know where he saw that button.

And then there is gunner Lance Johnson, a golden-haired surfer pro from the OC. Wonderfully played by the Santa Barbaran actor Sam Bottoms, who actually surfed, Lance brings Cali straight into the jungle mix when he is recognized by Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore, a Stetson-wearing nutball with a Yater Surfboards t-shirt who, as the Redux makes clearer, unleashes his murderous “Ride of the Valkyries” raid in order to seize a beach with a good break so that Lance and two other Southland bucks can ride. The napalm drop fizzles the plan by unleashing onshore winds, but not before we witness the violence and carelessness and cowboy Reb values that lurk in the shadows of the Endless Summer, perhaps the final shore of America’s myth of innocence.

That said, Lance does retain a kind of befuddled sparkle as they head further up the Nung river. The Dionysian anarchy that so defines Apocalypse Now, both in its famously chaotic production and its views of war, is often headless and destructive, but a mad surfer Tao runs through it as well. And Lance survives — that is, if his soul does survive the slaughter of civilian innocents he participates in — by playing: with LSD and puppies and face-paint and purple-haze flares and the kids at Kurtz’s compound. A friend writes him about Disneyland; he looks around and says “Fuck, man, this is better than Disneyland.” But though a fool, he nose-rides through Nam’s wilderness of pain with a naive druggy grace. The character was originally slated to die like his PBR peers, but he lives in the end, led away from Kurtz’s compound by the hand, like a child. Then again, as Jimbo Rimbaud sang, all the children are insane.

Kurtz represents the other side of insanity, not a child but a saturnine, toxic king, ready to die and, just maybe, be reborn. (We know this from his copies of The Golden Bough and Jessie Weston’s From Ritual to Romance, which suggest that Coppola wanted to one-up the Hero with a Thousand Faces that George Lucas swiped for Star Wars with a darker mytheme.) Embodied by a slurring Brando, a famously addled Hollywood insider-outsider, Kurtz is less a meditation on American imperialism gone wrong than on the sort of strange prophets that crystalized in the ‘70s — in other words, he is first and foremost a cult leader. The glimpse of Manson’s face on Chef’s newspaper is a clue here, though Brando’s implacable presence reminds me more of Adi Da, from his Garbage and the Goddess phase, and Jim Jones, who dispatched his own children in the jungles of Guyana less than a year before the film debuted.

These men are nothing without followers, which is why you need the coked-out Dennis Hopper, a journalist “gone native,” his mind so enlarged his brains fell out, his moral compass totally fritzed by the nondual paradoxes that crazy wisdom sages embody when they do evil things. And yet even a mad cult leader can possess a secondary moral force, which is to reveal the hypocritical violence implicit in the status quo that surrounds them. David Koresh may have been schtupping the teens, but Waco also revealed the ATF and the FBI in their true and far more terrible colors. If Kurtz has a motive at all, it is his refusal to stomach the lies and band-aid hypocrisies that sustained the war effort. “And they call me an assassin,” he mumbles early on when Willard gets the assignment, the reel-to-reel tape sprinkled with eerie cosmic noise. “What do you call it when the assassins accuse the assassin?”

This recursive j’accuse is the inevitable rejoinder to American exceptionalism, especially when it is enacted through force, as in Vietnam, or the Indian wars, or twenty years of Afghanistan. It goes all the way back to another mad prophet of mechanized violence. “Where do murderers go, man!” asks Ahab towards the close of Moby Dick. “Who’s to doom, when the judge himself is dragged to the bar?”

Unlike either the brass or the grunts on the boat, Kurtz and Willard share the knowledge of Ahab’s insight and the moral maelstrom it unleashes. “Apocalypse” means revelation, remember, and what is revealed all too often in the real course of things is Kurtz’s world of “horror and moral terror.” Should we make a “friend of horror” today, as Kurt demands, with so many already unleashed and so many yet to come? But to deny the horror, or to pretend it is not incessant, is to deny (our) reality. And so the stone buddha returns for the final shot, his dharma eye nearly superimposed on Willard’s thousand-yard stare, imperturbable, in flames.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Oh my brother! We really must chat soon!

Da Free Kurtz is waiting for us...

“Embodied by a slurring Brando, a famously addled Hollywood insider-outsider, Kurtz is less a meditation on American imperialism gone wrong than on the sort of strange prophets that crystalized in the ‘70s — in other words, he is first and foremost a cult leader. The glimpse of Manson’s face on Chef’s newspaper is a clue here, though Brando’s implacable presence reminds me more of Adi Da, from his Garbage and the Goddess phase, and Jim Jones, who dispatched his own children in the jungles of Guyana less than a year before the film debuted.”

Just want to suggest that US miltarism and all versions of imperialism, along with the bizarre ideas and practices that fuel it, is itself a cult, in fact one of the most powerful cults of magic transformation/rebirth through blood sacrifice ever propagated. It is hard to see anything Jim Jones did that LBJ, Mcnamara, Kissinger and Nixon didn’t do hundreds of times over. The fact that the cult of mass killing endures is nowhere more evident than our latest blood bath in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria. Manson was as American as those who did the massacre at Wounded Knee.Trying to make distinctions between the cultic criminal activities of a state and of the smaller local iterations of cults of violence seems to me an invitation to self deception. It turns real children burning with napalm or spattered with the blood of drone-killed relatives into statistics and polemics. What is freedom for and what does it mean if we can not declare ourselves at least free enough to refuse to be a hired killer?