Dharmalands

Eden Ahbez's California Dream

Exotica is the art of ruins. — David Toop

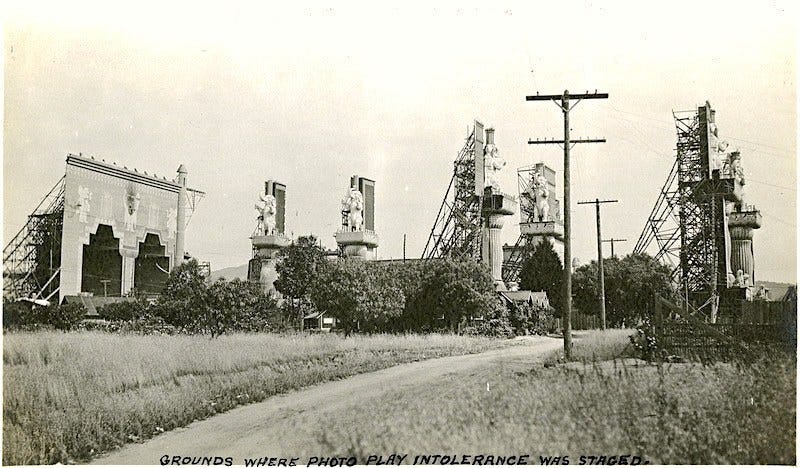

There are a lot of Lands in my homeland. Pocket worlds are tucked away throughout California, a place that, for many, already appears beyond statehood or history as a dreamland, a Realm of its Own. Disneyland is the most obvious of these pocket worlds, a theme park utopia that subdivided itself, through some imagineered mitosis, into multiple smaller Lands: Adventureland, Frontierland, Fantasyland, and Tomorrowland (the most changeable of the lot). Later, when Disney iterated California itself into yet another themed domain, they called their new park California Adventure. But you know they wanted to call it Californialand, which is where so many of us now live: a themed dream, circulated through technology, film, drugs, food, and wellness practices, that is now crumbling into the burning, desiccating, maniacally subdivided, and ancestrally blood-soaked ground, staging a colossal reckoning that suggests nothing so much as the huge Babylonian set that D. W. Griffith left to molder on the corner of Sunset and Hollywood after he filmed Intolerance in 1916. Those structures were later reborn visually as the Hollywood Highland Center mall, another reminder that our enchanted consumer paradise is built on ruins.

California’s Lands are aspirational, speaking at once to possibility, novelty, and the desire to do your own thing. But they also offer the crucial quality of otherworldly transport, whether it’s to the plastic purgatory of Legoland or the never-tell romper rooms of Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch. Some Lands are explicitly spiritual, like Lomaland, a large Theosophical Society enclave set up on Point Loma by Katherine Tingley in 1900. San Diegans would visit the exotic grounds on weekends, taking in the preachy Greek plays, the avocado groves and fruit trees, the magical amethyst windows, and other marvels crafted by the community’s industrious and prim esotericists.

Lomaland closed in 1942, which was around the time that a new Land started blooming up in Montecito. Lotusland is a gorgeous, diverse, and sometimes fanciful garden, which you still can (and should) visit today. It was crafted by another colorful mystic personality: Madame Ganna Walska, a mediocre Polish opera singer and high-society dame who was married to the hatha yoga pioneer Theos Bernard when she first developed the property, initially intended as a retreat for Tibetan monks.

I like to imagine the ambrosial aromas of Lotusland drifting and coalescing into the most recent California Land I’ve visited: Dharmaland. Dharmaland is not a physical place but a space of the imagination, mapped but never realized by the musician and wanderer Eden Ahbez (1908 — 1995), one of the most singular spiritual seekers ever to call the state home. In other words, Dharmaland is a record, recently reconstructed, reimagined, and released by the combined forces of the Swedish exotica band Ìxtahuele and the indefatigable Ahbez historian and archivist Brian Chidester. It is a monument, a memorial, and another enchanted Land all rolled into one.

To the extent that he is known and remembered, Ahbez is known and remembered for his song “Nature Boy,” which became an unlikely hit for Nat King Cole in 1948. If you haven’t heard the song in a while, or even if you have it soaked in the sweet and melancholy loam of your soul, I recommend you bend an ear to Mixmaster Morris’ fabulous melange of “Nature Boy” versions, one of which has the wit to klezmerize the schmaltz implicit in the melody — a schmaltz that later forced Ahbez to settle out of court with the Yiddish theater star and composer Herman Yablokoff, who claimed the tune was plagiarized from his song “Shvayg mayn harts" (שװײג מײן האַרץ, “Be Still My Heart").

Regardless of the lift, “Nature Boy” is a sui generis glade in the landscape of American song, and its final line — “The greatest thing you’ll ever learn / Is just to love and be loved in return” — a Serenity Prayer of bohemian pop, equally naive and equally true. But perhaps the most remarkable thing about “Nature Boy” is that its songwriter actually walked the talk. Please have a gander at this clip from a 1948 TV show called We The People:

Yes that’s right folks, this is 1948, and that’s a hippie. Born George Alexander Aberle in Brooklyn in 1908, he transformed himself, like so many, when he arrived in Los Angeles around 1940. He took the name Eden Ahbez (whose exact spellings drifted), started meditating and doing yoga, and wore robes. He basked in the teachings of the local gurus Paramahansa Yogananda — the first rock-star godman in America — and Jiddu Krishnamurti, who invoked another crucial California Land with his famous declaration that “truth is a Pathless Land.”

Ahbez worked at the Eutropheon, a health food store and raw food cafe on Laurel Canyon Boulevard, whose owners followed a Lebensreform philosophy influenced by the earlier, pre-Nazi Wandervogel movement in Germany. These same currents also inspired Bill Pester, the ür (or über-) hippie who lived in a palm-frond shack in Palm Springs all the way back in the teens, and who was a model for Ahbez and his outdoorsy crew of raw-foodist pals known as the “Nature Boys.” (Folks interested in the German Romantic roots of the California hippie should dig up the organic farmer Gordon Kennedy’s book Children of the Sun.)

The Nature Boys would alight for the winters to one of the palm canyons in Coachella Valley. But Ahbez, who crossed the country a few times on foot, was particularly fond of living outside and did it throughout his life. He sometimes camped with his young family near the Hollywood sign, even though “Nature Boy” insured him at least some royalties for the rest of his life. He spent tons of time in Big Tujunga Valley, where he built an outdoor oven that still stands. For the most part he continued his plein air ways until 1995, when he died from a head-on collision in the Econoline he then called home. In one phone message recorded near the end of his life, he referred to himself as “the sound asleep, wide awake man of Zen.”

Following the success of “Nature Boy,” Eden continued to write, record, and publish songs, but never hit it big again. In 1960 he released his only album, Eden’s Island. Recorded with a crew of solid jazz musicians in a single day, the record features the core ingredients of exotica: languid rhythms, wordless female vocals, frog croaks and bird songs, textured percussion, vibraphones humming with naive melodies. But instead of the usual fruity mai tai, Ahbez brews up something singular from this mix: an enchanting and prayerful expression of the nature mysticism that he carried in his bones. A number of songs have him reciting deceptively simple verses that use his fantasy island mise en scène to stage a deeply Californian mode of informal and earthy spirituality. (Don’t forget that California appears on the earliest explorer maps as an island.) The album celebrates boys and girls falling in love on the beach and the food and pleasures of the marketplace, but it also gives voice — especially in the timeless “Full Moon” — to the darkness that lies on the face of the deep, a cosmic melancholy he calls the “thrill of loneliness.”

This is not your daddy’s (or grand-daddy’s) exotica. Much more typical of this primitivist mood music — which wasn’t named “exotica” until it was rediscovered by hipsters decades later — was the Californian composer and film scorer Les Baxter. Baxter helped lay the template for the genre by producing the Peruvian singer Yma Sumac’s divine Voice of the Xtabay (1950) as well as his own taboo romps, the first released in 1951 as the sub-Stravinskyean Ritual of the Savage (Le sacre du sauvage). In his book Exotica, David Toop writes that Baxter had “strange, inventive ideas that could lift risible arrangements and melodic schlock into a realm of warm leatherette enchantment.” Even Sun Ra was a fan.

Of course, any sense of authenticity in the room (or the bachelor pad) was an ethnographic ruse. Most of this stuff was too fabulously fake to even be described as “appropriation.” The actual psychogeographic roots of exotica lay in Southern California’s own savage phantasmagoria, which over the decades bathed the southland in a garish visionary primitivism that excreted all manner of flotsam, from the La Brea tar pits to the “Aztec” hotels of Robert Stacy-Judd, from the delirious objets of tiki culture — Adventureland again — to the low-brow fetishistic art of La Luz de Jesus Gallery, from Malibu-beach-bum Gidget shacks to the hulking Easter Island monsters of the sculptor Stanisław Szukalski. As Baxter admitted when discussing the world travels that appeared to influence his work, “I don’t think I got any further than Glendale.” He didn’t have to.

Rather than reveling in pulp primitivism, however, Ahbez’s music presents a rival California vision of premodern holism, one that is as limpid, simple, and nourishing as the hand-carved wooden flute he played, or a plate of fruits and nuts for dinner. As he sings in the marvelous swing tune “Child of Nature,” collected on a rarities album also curated by Chidester:

I’m a child of nature / I’m happy and healthy and free / Yes I’m in love with nature / And she’s in love with me.

Ahbez didn’t stay in Glendale to pursue his love affair, but he didn’t have to wander far either. California’s temperate Southland offered copious and inviting arroyos, peaks, and palm deserts, especially in those less crowded and less smoky days. Even the metropolis held marvelous Lands, like Topanga Canyon or the Self-Realization Fellowship’s Lake Shrine Meditation Gardens (pictured on the cover of Eden’s Island, and still a worthwhile destination today). Living outside, meditating, writing songs and eating clean, Ahbez seemed to tap into deep forces that he paradoxically expressed in mostly gentle modes of whimsy.

Sure, Eden’s Island sounds corny at times, though it’s too mellow and pensive and earnest for boozy kitsch. But as Phil Ford declared in a marvelous episode of the Weird Studies podcast devoted to exotica, “corniness is the other side of the marvelous.” Here is the key point: to experience such marvels you have to risk an unsophisticated, even credulous love for corn, and part of that love involves a willingness to submit to what Ford calls a “magical hermeneutics” capable of transforming marginal chunks of pop culture. As he writes in the wonderful 2008 essay that inspired the episode, exotica is “less a genre of music than a class of cultural objects that share a characteristic projection of the self across boundaries of space and time.” This makes it essentially psychedelic — “film music for daydreams” — and Ford draws out that historical connection in his essay, which argues that while the hippie movement that Nature Boys like Ahbez prophesied looks like a radical rejection of the space-age bachelor pad of ‘50s consumerism, tendrils of transcendent yearning link the exotica imaginary to the earnest if stoned mysterioso to come.

Eden’s Island is a visible bridge between these worlds, a Land real enough to serve as a sonic home for the Nanao Sakaki sentiment that becomes a leitmotiv for Ford’s essay: “we are primitives of an unknown culture.” Exotica, then, answers a key koan of hippie California: how can a science fiction become an archaic revival?

Ahbez wrote the twelve tunes that make up Dharmaland just after Eden’s Island was released. But for various reasons, including the poor sales of that album and the death of Ahbez’s wife from bone cancer, the songs never made it off the page. Instead, he recycled many of the melodies for later suites and poems. The lead sheets lay for decades in the Library of Congress until unearthed by the diligent and obsessive Chidester, who is currently making a documentary about Ahbez that I suspect will be wonderful. The tunes were mostly just sketches, sometimes barely more than a title and melody. Think of them as the fragmented foundations of some never-completed ancient temple, now reconstructed and elaborated by Chidester, who named the suite Dharmaland after one of the songs.

Chidester also recruited Ìxtahuele, a polished Swedish instrumental quintet whose embrace of exotica is classy rather than crass and exploitative. Just see how smoothly and sweetly they support psychedelic soul artist (and Cali native) Kadhja Bonet’s wordless vocals on the Dharmaland single “Manna.”

Like Eden’s Island, Dharmaland is a psychogeographic record, though here the landscape is explicitly Californian. Songs reference Frisco, the San Joaquin Valley, the waters of Lake Arrowhead, and the Grapevine, which, as all Interstate 5 drivers know, rises like an early sign of deliverance at the close of the purgatorial southbound journey through the “ole Joaquin.” According to Variety, Ahbez himself once walked between LA and Bakersfield through the Grapevine in order to promote Eden’s Island.

This shouldn’t surprise us. Like many a later longhaired rock-star seeker, Ahbez was perfectly willing to pimp his mystic in the right situation. In “Dharma Man” — an upbeat bongo-fied finger-snapper sung on Dharmaland by ukulele player and comedian Denny Moynahan (aka King Kukulele) — Ahbez reflects on his “Nature Boy” experience from a decade previous: “They took my picture / Gave me a spread / Man I was a-ballin’ and a-knockin’ ’em dead.” Joe Romersa, who collaborated with Ahbez later in his life, spices up the tune with some amphibian trills from Ahbez’s own handmade flute. The result is marvelous corn, a fun testament to the rarest of white yogi songwriters — one capable of not taking himself too seriously.

Romersa is one of a number of Ahbez friends and collaborators that Chidester recruited for Dharmaland, including Eden’s Island percussionist Emil Richards, who plays waterphone on the expansive, moody title track. Other old pals take over most of the album’s lyrical chores, which include the sort of pensive poetic recitations familiar from Eden’s Island. Like the bamboo timbre of Ahbez’s flute, these contributions thicken the memorial density of the project, invoking traces of a good man gone, although the craggy, sometimes unpolished voices don’t always serve the musical setting.

Despite a few lapses, Dharmaland is a magical album, and a lot of that magic lies with its arrangers, Ìxtahuele’s Henrik Magnusson and Mattias Uneback. Though the original melodies were crafted in the early 1960s, Magnusson and Uneback refused to freeze their settings in lounge amber. Instead, they allow the intervening years to seep in, giving us something informed by Brian Wilson as much as Martin Denny. Fitting, since Ahbez himself showed up for some Smile sessions in 1967, no doubt leaving a mark on the sensitive boychild.

Listening here to the gorgeous instrumentation of “New Anthem” or the playful, jingle-like vocals of “The King and Queen of Waters,” I often found myself thinking of Wilson, and his own Southland path between the corny and marvelous. I especially thought of a track from 1971’s Surf’s Up, “'Til I Die,” whose plaintive vibes filter old-soul melancholy through a guileless wonder. Wilson’s earthy invocation of dissolution in “'Til I Die” — a rare meditation on death in pop — echoes the Ahbez poem that Chidester reserves for Dharmaland’s closing tune, most of whose verses were found scrawled on the cover of an early copy of “Nature Boy”’s sheet music:

And in the lonely chanting of the sea / I heard the word that means all words to me / And in the fantasy of cloud and sky /I see the one who lives while all things die

And in the endless rolling of the spheres / the eternal silence stills the noisy years.

It was strange and wonderful / Like moving among the objects of the world / As though there were no objects to move among / As though there was no world / As though there was no mover.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

faaascinating. thanks, erik.

https://wfmu.org/archiveplayer/?show=105491&archive=204049

WFMU's Gaylord Fields did almost an entire program on the album this past July 4th. The interviews are great as is the music.