I rarely read reviews of films I know I am going to see beforehand, so you might just want skip this or scan it before scooting your butt over to Netflix to watch The Disciple, the Indian director Chaitanya Tamhane’s deeply attuned, clear-eyed, and exquisitely felt tale of a student of Hindustani classical music living in contemporary Mumbai. The Disciple is a rich reflection on art, devotion, lineage, and practice — and the disappointment, loss, and sense of failure that attend the almost inevitable fray and fragmentation of those values, particularly amidst our hypermodern meltdown. It’s the best contemporary movie I have seen for a couple years, and I am surprised that Netflix isn’t making a bigger deal about it, though it appears the word is getting out.

I was, admittedly, already set up to love the thing, as I have been into both Indian film and especially Indian classical music for some time. After a somewhat typical stoned teenage fascination with Ravi Shankar, I stayed with the music, drawn to the five-dimensional chess of its rhythms, its vibrant sound-world of resonance, drone, and microtone, and that unparalleled sense of emotional transport and atmospherics that attend the almost metaphysical science of the rag. A few years ago, I committed to learning more about the music, and so I poured over books and album copy, listening guides and websites. I can now confidently say that, in my understanding of this music, I have graduated from kindergarten to first grade. But one thing I have learned to treasure is that the queen of instruments is the human voice.

The aesthetic milieu of The Disciple is khyal, the dominant style of Hindustani classical music, which is no more central to the lives of most people in India than Western classical music is to most Americans. Khyal singing is noted not just for its technical complexities but for the marvelous and expressive ornamentation allowed to vocalists, whose swoops and dives, meditative digressions, and teasing dalliance around the tonic more than justify the etymology of the term, which comes from the Persian for “imagination.” In this, khyal stands in some contrast to the sterner rigor of the older dhrupad style, most associated with the sublime Dagar family. Pandit Pran Nath, known to deep fans of Terry Riley, Jon Hassell, and La Monte Young, represents a style of khyal that emphasizes slow microtonal melisma and subtle appreciation for individual notes.

The Disciple is peppered with gorgeous performances, as well as some instructively mediocre ones. Indeed, one of the marvels of the film is that the actors portraying musicians here are all actual musicians, for once undermining the typical undercurrent of unreality produced by actors feigning competence in fields other than feigning. Even the audiences Tamhane arranged for the concerts are real-life lovers of classical music; for khyal nerds, one of the hidden gems is observing those audiences knowingly bob, bend, and follow the tala.

The titular disciple of Tamhane’s film is Sharad (Aditya Modak), a twenty-four-year-old student of the elderly master he and his fellow students call Guruji (Arun Dravid). Sharad is devoted to his guru, but not in a creepy culty way. He practices diligently, at the expense of making money or chasing girls or dealing with his mom. He also gives Guruji massages, helps handle his affairs, and later cares for him in his dotage. This is all pretty standard stuff for traditional musical pedagogy in India, where 0l often live with their gurus for years, and submit to a rigorous, long, and immersive tutelage. Guruji tells Sharad that his own guru, the mysterious Maai, who insisted on the ascetic, spiritual, and anti-commercial aspects of the music, did not even let him perform until he was 40.

But we are not in traditional India; we are in modern Mumbai, where an often frustrated Sharad rides his motorbike late at night, listening on his iPod to rare recordings of Maai’s lectures calling for sacrifice and surrender. He watches as no-names on talent shows blow up into singing sensations on the Internet, where he also finds porn to ease his loneliness. The naively devoted Sharad must make his way in a world that cares little for his art, which — as a cynical and corpulent critic informs Sharad in a key scene — also features its own cut-throat and highly compromised aspects. The tension between traditional aesthetic ideals and the corrosion of hypermodernity is hardly a novel theme, but Tarhane renders it with fine nuance, his simultaneously sympathetic and skeptic eye avoiding all easy contrasts, resulting in a bittersweet tone leached of easy sentiment.

After all, like so many “traditions,” khyal as we know it is as much a product of modernity — even of modernism — as a feudal culture hold-out. As the novelist and khyal singer Amit Chaudhuri writes in the delightful and illuminating book-length essay Finding the Raga (2021), some of the most distinctive features of khyal arise in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, as the economic basis of the traditional court musician is rapidly undermined. One of these formal features includes a new phase of the rag in which the radical slowing-down of the rhythm allows for the abstraction and deconstruction of the compositions that form the meat of the performance. By the 1920s, he notes, “we’re witnessing a radical non-representational shift whose inclinations are modernist.”

The Disciple certainly isn’t the first Indian film to play with the complex tension between Indian music and modernity. One of the most powerful Satyajit Ray films, surpassed only slightly by Pather Panchali (1955) in my book, is The Music Room/Jalsaghar (1958), which focuses on a listless aristocrat of dwindling fortunes whose aesthetic appreciation for the concerts he spends his last coin to stage is juxtaposed with an upstart money-hustler who supports musicians for status alone. I also think of the fabulous opening sequence to another Bengali film, Ritwik Ghatak’s impeccable The Cloud-Capped Star/Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960), which my long-lost pal Wef rightly said belonged to “the highest order of cinema.”

In that opening sequence we hear a young singer, Shankar, vocalizing by the side of a lake. He is devoted to his craft, but he is also a lay-about who depends on his loving sister Nita, who we see smile as a train — that great and noisy engine of industrial modernity — passes on the far side of the lake, closing in on what remains of their idyl. The abrupt curtailment of the song, and the non-diegetic instrumentation as well, is totally intentional. Ghatak, a Marxist, brought a playful and materialist edge to his sound editing as sharp as Godard’s, and the void you hear for a moment is, well, the void. Shankar’s awkward face scratch is a reminder that however much his craft allows him to channel the sublime, he has no money for a shave. In a later scene, Shankar gets told off by a hard-working merchant before we cut to a decidedly non-classical performance by a Baul singer, one of Bengal’s legendary wandering minstrels.

This is a gorgeous slice of Baul blues, and at first it seems to speak to all that is lost — devotion, enchantment, earthy mysticism — as the world of the train brings the rule of cash and credit into ancient village life. But the lyrics speak to an aesthetic or even philosophical dimension of modernity (and modernism) that filmmakers critical of dogmatic religion — like Ray and Ghatak — also shared: the recognition, as existential as it is political, that humanity has become unmoored from metaphysical guarantees. No boatman, no one on the other shore.

Baul songs are influenced by Sufism and the spontaneous, immanent spirituality that courses through both Buddhist and Hindu tantra, as well as the nomadic lifestyles many Bauls prefer. This lineage allowed for a lyrical freedom rare in religious-oriented “folk” music, which is partly why the ‘60s generation fell in love with the Bauls. (On the cover of John Wesley Harding, Dylan is grinning beside the brothers Luxman and Purna Das, flown over to Woodstock by Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman to perform for the budding hippie scene.) As such, I have no idea if the lyrics in the Ghatak film are “traditional,” or even what that really means. I do know that the sentiment our singer expresses combines and juxtaposes the sacred yearning of devotional music, of bhakti, with the more abstract and sometimes harrowing confrontation with an impersonal cosmos.

This is one of the keener flavors of the modern spiritual predicament, and by “spirituality” here I don’t mean the self-involved wellness cult but something more like an a hunger that refuses both the cynicism of materialist mercantilism and the authoritarian appeal of reactionary traditions. For obvious reasons, modern art and especially music is one of the places we can find and taste this flavor (or rasa), whether with Stravinsky’s Symphony of Strings, or Terry Riley, or Leonard Cohen, or, if we follow Chaudhuri, khyal. One of the remarkable features of The Disciple is that, simply because of the parallel of guru and disciple relationship, Sharad’s vexed relationship with Guruji can speak to this spiritual predicament without saying a single word about religion explicitly. Even the voice of Maai, the most old-school traditionalist in the film, offers hard contemporary truths rather than consolation, demanding of students “the strength to look inwards with unflinching honesty,” something we are not sure Sharad is quite up for until reality gives him no choice. “The truth is often ugly.”

In the final scene of the film, we see how the fraying threads of ancient song still tie together, however brokenly, this yearning and this ugliness, or at least banality. Tarhane sticks to a single establishing shot (as he has done throughout the film), a frame that allows for both a cool transcendentalism and a sensitivity to the social conditions — audience, schoolroom, household — that shape what is, admittedly, a rather subdued drama. Here an older Sharad, now a father and working at a business you wouldn’t bet on selling Hindustani music, sits on a clattering Mumbai subway as a young singer ambles down the aisle, plucking a drone on a crude tanpura. “At the edge of a well, oh seeker / I sowed a tamarind seed,” he sings with a familiar melancholic folk pang. Sharad pays attention, and then goes back to staring out the window. No boatman, no one on the other shore.

Upcoming Events

(•) Later this month I will be participating in a one-day conference at the Pacifica Graduate Institute called “Accessing the Ineffable: Depth Psychology, Religious Experience, and the Further Reaches of Consciousness.” The gathering will feature talks on a variety of far-out mindstates, including dreams, seances, and spirit possession. Psychedelics will be addressed in talks by Christopher Bache (LSD and the Mind of the Universe, 2019), William Barnard (Exploring Unseen Worlds: William James and the Philosophy of Mysticism, 1997), and myself. The all-day event will take place on Saturday, June 19, starting at 9am PT, and you can register for it here. Special offer: all Burning Shore subscribers are welcome to register at the Pacifica Student Rate. Additional scholarships are available as well for those in need. Please contact retreat@pacifica.edu for further information.

(•) Once again, I failed to get this mailer out before the monthly online gathering of the San Francisco Psychedelic Sangha. We had a fine old time. I rolled out a guided meditation I have been thinking about for a few years: Creature Metta, an attempt to remix the basic metta meditation model into a more creaturely direction, working with the affects — loving but also difficult — that inform our relationship with animals, including phobic beasts and creepy-crawlies. Practices of imagination are practices of psychedelic dharma. The next gathering will be on Saturday, July 3, at 6 pm PT. As always, a mix of practice, talk, and dharmanaut conversation. I hope to be be joined by a special guest; sign up here.

Links

(•) Last month I had about as much fun as I have had on Zoom since the pando descended: a three-and-a-half-way conversation over at Harvard’s Center for the Study of World Religions. The rich discussion, which was just posted at the CSWR, was called “Between Sacred & Profane: Psychedelic Culture, Drug Spiritualities, and Contemporary America.” My interlocutors included my pal and colleague Dr. Christian Greer, the author of a mind-blowing dissertation called Angel-Headed Hipsters: Psychedelic Militancy in Nineteen-Eighties North America, a ground-breaking study of the Church of the SubGenius, zine culture, Hakim Bey, Bob Black, etc., that will soon(ish) be published by Oxford. The other gabber was Dr. Gary Laderman, who writes and teaches about psychedelics as well as death, which informed our conversation in a subtle but powerful way that Gary later wrote about beautifully. The extra half in our three-way chat was provided by Dr. Charles M. Stang, director of CSWR, whose book Our Divine Double (Harvard, 2016) is required reading for Valis exegetes.

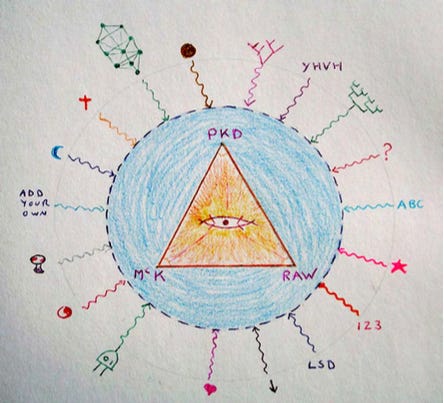

(•) Though High Weirdness started out as a book about Philip K. Dick, and the SF author gets the most ink, I have spent most of my time since publication talking to folks about Terence McKenna and Robert Anton Wilson. So I was particularly pleased to read a substantial review of the book by PKD bilbiophile, collector, and critic Lord Running Clam, who read the admittedly dense text like “a slime mold sucking up sustenance as it motates through life.” I thank LRC for recognizing how much the PKD sections serve as an introduction to Dick’s Exegesis, and I thank him even more for pulling the following chart of the book out of a dream state.

In LRC’s playful lingo, the diagram suggests that High Weirdness “treats reality as a subatomic particle that will yield its secrets if only we smash it hard enough with enough inquiricles.” A new word every day! LRC’s review appears in the latest issue of Patrick Clark’s wonderful and long-running PKD Otaku, which this time also features a fascinating and, yes, nerdy collection of cover art from Chinese PKD translations. The whole issue can be downloaded here. LRC also let me know that, in commemoration of Dick’s death forty years ago next year, the third Fort Morgan PKD fest will be held March 1-3, 2022 in the Colorado town where the cracked seer’s grave resides.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Just finished the video Between Sacred & Profane: Psychedelic Culture, Drug Spiritualities, and Contemporary America. Good stuff, so good that it made me grieve a life not lived.

I often wonder what my life would have looked like had I pursued academia, but traditional education and I always had a difficult relationship. The video made me long for that alternate timeline of inquiry and dialog shared with others. That leaves books as my guide and, Jesus, there's just so many books unread. I recently finished reading Horgan's Mind-Body Problems. Got about 1/4 of High Weirdness left to read...all wonderfully heady stuff.

In a related event, had a dream about my maternal grandfather last night. This alone was weird, since I haven't dreamt of him for decades. He said, "I really wished you would have gone to college." I offered an excuse about age, temperament, time, and money. Then he said, "Well, you were right about Roe v. Wade though." This made the dream gush WTF. He died when I was 14 and I hadn't seen him in the four years previous.

I know I've just scratched the surface of Everything, but thanks for providing your continual insight.

PS, If you got the time, I'm curious: have you read Daniel Quinn's "Ishmael"? If so, what did you take from it?

Thank you! This looks outstanding.