In my last Ask Dr. D., I provided a short list of some of my favorite cosmic comix. One of the earliest items was Man from Utopia, a strange and unsettling 1971 publication from the hand of Rick Griffin. (Please do not confuse this with the 1983 Frank Zappa album, and definitely not with the latter’s craptastic cover.) Born near Palos Verdes in 1944, Griffin became one of the most singular and enigmatic artists of the psychedelic era. He was a zealous iconographer of the Cali cultural zones he lived through — surfing, psychedelic rock, acidheadfuckery, and the Jesus Movement. His work lies close to my heart, plucking strings at once weird and sacred, and I wrote an extensive two-part article about the man and his art for HiLoBrow almost a decade ago.

Griffin produced and contributed to underground comix, but he remains best known for the rock poster art he produced in late-‘60s San Francisco. Like many, I bow down amazed before his legendary Jimi Hendrix flying eyeball poster (BG-105), perhaps the supreme eidolon of the era. I also owe a lot to the biomorph erotics of his album cover art for the Dead’s Aoxomoxoa, which worked like an initiatory mandala on my wee stoner mind. But Man from Utopia is the pinnacle, or, perhaps, the pit of Griffin’s psychedelic vision: convulsive, sexual, hermetic, intensely sacred and intensely profane.

Despite its throwback cover — whose unfortunate Gumbo image, anomalous in the Griffin catalog, I make no apologies for — it is not really a comic. Instead it reads as a portfolio of more-or-less thematically related images, which may have suffered the additional confusion of getting mixed up by an addled Griffin before getting handed off to the printer. The themes reflect Griffin’s core obsessions: sex, death, Christ, flesh, liquids, goofy japes, and lysergic gnosis. Man from Utopia is an opus, one that Griffin felt strongly enough about to eschew the usual pulp, printing the cover on good full-color card stock.

It emerged from a turbulent time in Griffin’s life. Things had gotten apocalyptic on the Haight, and, following a brief sojourn in Texas, Griffin and his family moved back to Southern California. Here he rediscovered his surfing roots and started spending time with some hippie Christians. His notorious intensity seemed only to increase — one account of the period describes an ability to “scare the living shit out of anybody not ready to deal with his quietly mysterious persona.” His internal struggle, which soon manifested as a singular conversion to Christianity, permeates the images in Utopia. Though hints of prophetic Christianity appear in Griffin’s earlier work, Utopia reflects a visionary opening to the man on the cross. But there is no dogma here, none of the preachiness that would show up in his subsequent work. Instead of born-again resolution, Utopia expresses the agonizing and often absurd turbulence of metanoia in motion — the kind of ferocious and foreboding almost-revelation known by all deep trippers.

The two-page spread I want to look at features no explicit Christianity, but is all about light, revelation, and mediation. The panel on the left is relatively simple in design.

Part of the density and intensity of Griffin’s work lies in the way he uses and reuses his own grab-bag of symbols, which means the resonance of his work increases the more time you spend with it. Some of his earlier strips reference the letters Alpha and Omega, which are identified with Christ in Revelation 22:13. Here we have an A=A announcement of some corresponding apocalyptic presence, a cross of final light that scares off the dark souls to the left and exudes stars and galaxies to the right.

The central image is itself a palimpsest of pop archetypes: lightbulb, 2001 starchild, holy babe emerging from a cosmic yoni, even an untimely echo of the alien Greys. Whatever we think about these component parts, which are not so much combined here as laminated together, we know we are facing a glyph of illumination. And for all the gnostic resonances of that term, illumination here is also a material fact: a lightbulb, an industrial commodity, its twisted base ominously reminiscent of a serpent coil or rattlesnake tail. This conjunction of sacred and profane may remind us of a photo that Breton wove into his marvelous Surrealist text Nadja, where “Mazda” is both the name of a trademarked Edison lightbulb and, as Ahura Mazda, the ancient Zoroastrian lord of light.

Griffin’s A=A lightbulb fuses the intense polarity found throughout his work, not just between sacred and profane, or cosmos and commodity, but between metaphysical being and the modern world. One key to this tension lies in a question asked by the scholar of religion Alexander van der Haven: “How do revelations work in a religious cosmos that is not transcendental?”

Van der Haven asks this in relationship to the mad writer Daniel Paul Schreber, whose late-19th-century religious visions included a God who communicates through a “light-telegraphy” of rays and vibrating nerves. In High Weirdness, I bring van der Haven’s discussion to bear on the lasers and satellites of Phil Dick’s VALIS visions. Either way, this is the point: Even if you still hold out for divine revelation, you are faced with the problem that, in a non-transcendental cosmos, revelation is still subject to the entropy and distortion that haunts any physical communications channel, whether lasers or light-telegraphs or Edison lightbulbs. Illumination is gnosis, but it is also a technological (or pharmacological) process, one that further refracts, degrades, and ironizes the divine message. Griffin’s lightbulb, then, is not unlike the famous hippie appropriation of the DuPont company slogan “Better living through chemistry.”

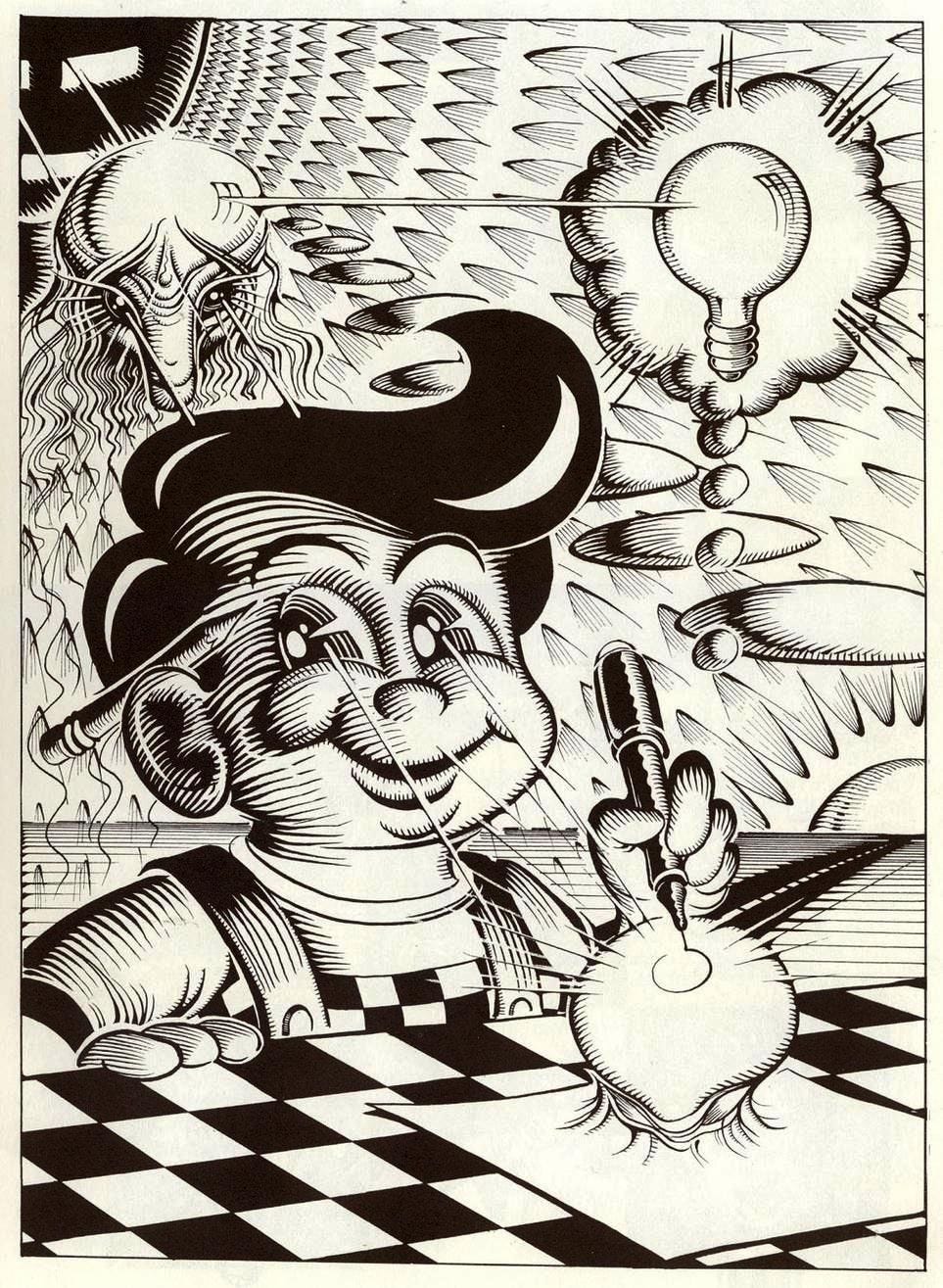

The irony of the profaned sacred, and the sacralized profane, is a key feature of acid mysticism, and it can come off as both funny and dreadful. Both vibes are apparent in Man from Utopia, especially in the twistier and more complex image that faces the A=A lightbulb on the right side of the spread.

While generations of older Americans will instantly recognize the central figure, I can’t speak for younger noggins, so here is the spoonful. This cherubic character is the mascot for Bob’s Big Boy, a once widely popular burger franchise that Bob Wian started in Glendale 1936. Like carnivore theophanies, large fiberglass statues of this kid appeared in front of many Bob’s Big Boy restaurants. Holding aloft the double-decker burger the chain originated, these figures in red checkered overalls charmed little kids like me with their cheery, accessible vibe, which nonetheless belied certain enigmas. Who was this sometimes very big kid? “Bob” we know is Bob Wian, and “Big Boy” the name of his famous burger. So is this a Big Boy serving a Big Boy? Does the possessive indicate that he belongs to Bob — praise Bob! — or does the smiling, big-eyed mascot exist more as Bob’s (or the burger’s) emanation or avatar?

With prophetic irony, Griffin recognized the Big Boy as an unparalleled icon of SoCal bulldada. But to further unpack the image, we need to consider an important subcategory of visionary or psychedelic art: the diagrammatic image. In a diagrammatic image, the picture plane is composed of multiple dimensions or realms that are linked together through various frames, portals, lines of light, arrows, vibrations, and morphological echoes. Griffin’s good pal Robert Williams provides many examples of such “meta meditations” in his extraordinary — and extraordinarily profane — canvases.

As this particular Williams painting suggests, the diagrammatic image is deeply linked to comic book art, with its plurality of panels and variable deployment of borders, overlapping frames, and connecting elements like lightning bolts, arrows, speech balloons, exclamation marks, and other abstract symbols that often represent sounds and emotions between and across individual frames.

There is also a link between the diagrammatic image and older traditions of illustration. In the early modern period especially, a variety of allegorical, esoteric, and alchemical images attempted to illustrate both cosmological and natural relationships. Here, for example, is the frontispiece to Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae (1646) by the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher, who pioneered the camera obscura and other optical marvels in an era when light was both a sacred radiance and an increasingly manipulable feature of the material world.

Griffin knew his esoterica, and was familiar with these kinds of pictures through his loving study of Manly P. Hall’s massive compendium The Secret Teaching of All Ages (itself born, like Griffin and Bob’s Big Boy, in Southern California). An earlier example of Griffin’s own diagrammatic images underscores this link to older esoteric maps. For the third issue of Zap (1968), Griffin contributed a deeply esoteric cover, as well as the following panel, which was based on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life.

The Kabbalistic tree, whose classic visual form also crystalizes in the early modern era, depicts an emanationist view of the cosmos. Sacred forces are “stepped down” through spheres and dimensions known as sephirot, which are usually ten in number and linked through various paths that have their own esoteric implications. Above and beyond the Tree lie three layers of the unmanifest — here accurately tagged as Ain, Ain Soph, and Ain Soph Aur — which in turn give birth to Kether, the supernal Godhead, or “highest crown.” Griffin illustrates this sephirot with a heavily abstracted mask based on Hopi Kachina figures. (You can think of this as appropriation or appreciation; like many ‘60s heads, Griffin had great respect for Native American cosmology and the peyote religion.) The Kachina Godhead then “speaks” a primal pair of forces: Binah and Chockmah, dark and light, here rendered as O and X, code letters that recur throughout Griffin’s work (including his term Aoxomoxoa). This yin-yang tension then creates the material, elemental world, where light spills down from the sun but can also, following the holy dove, be traveled upstream, back to the source.

Also linking the O and X, as well as Kether, is the Hebrew letter shin, whose three flickering flames reflect the letter’s link to fire. But shin is also an esoteric reference to Jesus. Athanasius Kircher and other esotericists in the early modern period, seeking to Christianize Kabbala, inserted the letter into the Hebrew tetragrammaton to form the name Yahshuah.

The lower dimensions of Griffin’s Tree are more “pagan.” Here the carnal procreative power of an Egyptian royal couple is manifested graphically as more elemental connections — a paternal (or patriarchal) lightning bolt and a maternal stream of milk, which feeds the babe of Malkuth, wailing away like Olive Oyl’s Swee’Pea from the last and loneliest sephirot, that darkling plane upon which we are all thrown at birth.

Many elements of Griffin’s “Ain Soph” resonate with “Big Boy”, which we might as well repeat here, in the context of the full spread.

Like “Ain Soph,” the “Big Boy” image represents the “stepping down” of illuminating power from the abstract supernal plane — pictured by the same Kachina figure, here partly obscured — to the profane world. But “Big Boy” is also notable for what it is not. Unlike “Ain Soph,” the image is not a mandala, that familiar symmetrical template followed by so many visionary and psychedelic artists, not infrequently to the point of cliché. Instead, this cosmic diagram is askew — the holy light emerges from the upper corner, where the Kachina Godhead is mostly cut off by the frame. From there the light passes through a more fleshed-out being, an enigmatic, long-haired alien (?) entity, and from there through the Big Boy’s eyes to the object he is conjuring to life with his pen. This object, which strongly resembles the “A=A” figure on the left of the spread — and which the Big Boy appears to be looking at across the gutter — echoes the entity’s strangely shaped head, even as that same morphology recurs as a lightbulb that pops up in a thought bubble on the upper right.

This lightbulb is an important key to the meaning of the diagram, which IMO is not so much about religious revelation as artistic inspiration. Again, like Breton’s “Mazda,” the lightbulb is both a modern industrial vector of illumination and a sacred echo of a higher being (though the long-haired entity seems to incarnate the weirder end of the holiness spectrum). But the idea bulb is also old-school cartoonese for the eureka moment of inspiration, a trope that the loremeisters on the Internet tell me goes back to Felix the Cat cartoons from the 1920s.

The lightbulb, then, is at once symbol, sign, and icon, a blazing self-referential condensation of the looping, concatenating vertigo that characterizes acid revelations. As Griffin writes elsewhere in Utopia, “Can't Quite Putcher Finger Onit . . . Some Kinda Warp.” Yet here at least, the elusive circuits of illumination birth a concrete aesthetic object that also appears on the page before: a weird embryo that, reminding us of the animism in animation, manages to rise off the page, echoing the shapes of higher planes that lend it heft and dimension.

The human artist at the seeming center of the action — goofy, oblivious, inevitably commercial — is hardly in control of the process. His personal idea bulb is embedded in a deeper circuit driven by strange forces working behind the scenes, forces that barely appear on the page before us. In other words, the human artist is a hollow fiberglass low-brow mascot of secret influences. That’s why his goofy draughtsman overalls merge into the mosaic pavement of Masonic temples, a table that here lies before that same darkling plane of Malkuth we saw at the base of “Ain Soph.” These black-and-white tiles are “emblematic of human life, checkered with good and evil,” and they are also where the aspirant undergoes initiation — an initiation that, here at least, is indistinguishable from inspiration, and illumination, and invasion — and something rather like infection.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Dr. Davis, I was imagining you would connect via light telegraphy to Pynchon’s “lives of the saints” style history of a light bulb at the end of Gravity’s Rainbow. Did you decide that Pynchon’s account was not sufficiently concerned with the revelatory to be thematic?

The whole thing (or almost) is viewable at the Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/man-from-utopia-1972/mode/2up Holy balls.