Runnin' With the Angels: the Harp of Van Halen

Eddie Van Halen and Terry Riley take different routes to the same sun-baked divine

The rock twilight is only deepening. If you have loved rock music and continue to do so, you are now living in a long gloaming punctured with boomer revenants whose importance to you returns, suddenly, sometimes after years or even decades, on the news of their passing. These avatars of a music that celebrated an ideal of unchecked youth and freedom are now old, and dying right on schedule.

David Bowie’s death in 2016 stood out for a lot of us, and for good reason. Bowie had been shedding skins forever, singing songs about the bardo, and artfully staging his own demise in advance. But there was also a particular power to the keening itself, especially from all those outcast, queer, nerdy weirdos who took refuge in the Starman’s elegant but unsentimental alienation in decades less loving of such margins than our own.

I was one of those weirdos too, but grief is a funny thing, even the mediated grief for media figures. You either feel it or you don’t. I was fascinated by Bowie’s death, and moved by how moved many of my friends were, but I was not sucker-punched.

This was in start contrast to the pit in the stomach that struck me late the following year, when I heard that the grave had claimed Malcolm Young, the minter of all those meat-hook AC/DC riffs his brother Angus had so wickedly filigreed.

My visceral reaction caught me up short. Sure I love AC/DC. There is a particular emotional snarl that can only be assuaged by “Problem Child” or “Whole Lotta Rosie,” real loud, and with embarrassing air guitar to boot. But I don’t listen to them much, and they certainly haven’t played the ongoing role in my soundtrack the way Bowie has. My pal Joe Levy has a theory, and I think he’s right: the difference is that by keeping Bowie in my mix, he became part of my changing, whereas my feelings for Malcolm Young are largely frozen in eighties amber, along with a much earlier self that now, for a brief flash, gets to be mourned as well.

All this got stirred up again last month when Eddie Van Halen died. I felt a sadness that seemed all the more surprising, because I never went deep on their records after 1980’s Women and Children First (still their most solid slab). And I totally lost interest after the departure of David Lee Roth, the most unapologetic of Jewish rock gods. Musically, Roth can’t hold a menorah to Dylan or Reed or Joey Ramone, or even Geddy Lee for that matter. But he radiated the most chutzpah, memorably defined by Leo Rosten as “that quality enshrined in a man who, having killed his mother and father, throws himself on the mercy of the court because he is an orphan.”

Van Halen was not the first record I bought—that prize goes to Kansas’ Point of No Return—but it was the second or third. As heavy-metal training wheels go, it did a fine job. What some might call hard rock I still hear as metal, but it’s light metal, or better yet, major metal—that is, metal forged in the spirit of the major key. Just listen to the mighty opening riff of “Runnin’ with the Devil.” I mean, this is a song about bottoming out with Satan, right? So after two pretty typical opening triads, you are ready for a minor interval or something equivalently dark or melodramatic. But no, Eddie’s riff is capped with some bright and shiny major thirds, as if fraternizing with the King of Hell is no more gloomy than driving to the beach in a convertible with the top rolled down. Which is another way of saying that Van Halen sounds a lot like Los Angeles: an infernal pact made with an endless summer you cannot afford to quit.

Some music historians understandably peg the sludgy Haight Street band Blue Cheer as metal pioneers, and their 1968 debut Vincebus Eruptum beats out Eddie’s “Eruption” by a decade. I can dig it. But for me, Van Halen remains the first definitive California metal record. Dropping a year after Star Wars, it was also a gritty-slick teenage dream that managed to shift the gears of a whole entertainment genre, for better and worse. Hair-metal and Yngwie, here we come.

After EVH’s death, the LA Times ran a great piece on his biracial, working-class immigrant upbringing in Pasadena. Writers on the band have long noted the class divide between the Camel-smoking Van Halen brothers and the sartorial flash of Roth, the son of a successful ophthalmologist. But Greg Renoff also shows how the boys reflected different cultural relationships with local Black and Mexican communities brought on by mandated high school desegregation busing.

But what really struck me in Renoff’s piece was the location of the Van Halen home. 1881 Las Lunas St., you see, is only about a mile from CalTech, and barely a 15-minute drive away from JPL, the aerospace research firm co-founded by the legendary Pasadena rocket scientist-cum-sex magickian Jack Parsons. Now, if you draw lines between those three locations on a map, they form a triangle. And while that’s pretty much true for any three non-contiguous points in physical space, that shouldn’t undermine the secret psycho-geographical message: EVH’s genius was a matter of technical drive as much as anything else.

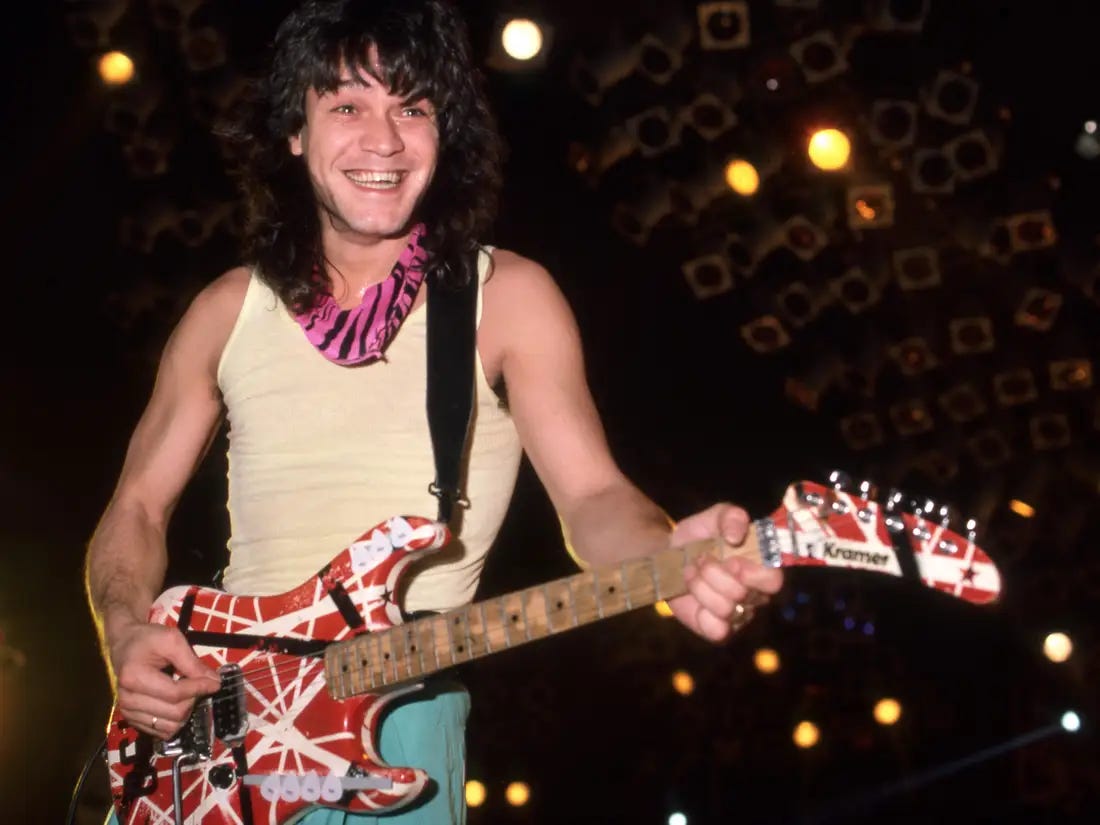

It’s not just that EVH was an obsessive maker who modified and constructed his own guitars—including the famous Frankenstrat—and earned a few patents. Nor was it that his hot hammer-ons and rapid-fire arpeggios required the cool technical mastery associated with conservatory pianists. Nor even that his playing trampled the distinction between solos and special effects. No—like Dr. Frankenstein, EVH knew how how to compel an inhuman life from his electrified devices.

Metal has always had a relationship to the inorganic—that’s why it’s called metal. In Eddie’s hands, metal got mercurial: shiny and liquid and fast as an integrated circuit printed with quicksilver. Robert Christgau, grudgingly admitting the singularity of EVH’s chops, nonetheless slagged his playing as “Technocracy putting a patina on cynicism.”

“Cynicism”? That’s too cynical for me. While there is a cold and wonky aspect to EVH’s playing, it lacks the imperious and disembodied demands of technocracy. What we might call his “mastery” is also wedded to a metamorphic radiance that is indistinguishable from play, not just the playfulness of a tinkerer or a kid—that winning Eddie smile—but the sheer exuberance of material technique pushed to the edge of incandescence, and then spilling over the edge. Eruption.

Digging into EVH’s geek bona fides a few days ago, I discovered a further dimension of his technical savvy. From the beginning, he tweaked the norms of tuning the guitar. Standard tuning requires a fudge on the B string, a sonic compromise that is required for all equally tempered instruments, which depart from pure or “just” intonation in order to modulate between different keys. Pure temperament adheres more closely to the actual physics of sound, but for that very reason goes south fast when you depart from the natural harmonics of the root pitch. (This is an over-simplification, but for a quick grok, check out this short video.)

Here is the metal bummer: the high gain on a distorted electric guitar unleashes aggressive harmonic overtones, which means that the imperfections in equal temperament badly mucks up certain chords, particularly involving major and minor thirds. Many rock guitarists just avoid those intervals, but Eddie just retuned the thing instead, manually flattening or sharpening the B string to match the demands of particular songs. (And then having to retune for the next song, which he often did on the fly.) This “sweetened tuning” is precisely what lends the major thirds in “Runnin with the Devil” their bright and happy hue.

Discovering all this gave me a synchronistic shock, I gotta tell you, because the other record I wanted to write about here, and that at first seemed to have nothing to do with Mr. Eddie Van Halen besides California, was the 1986 Terry Riley release The Harp of New Albion. I have been listening to Riley’s modal and mystic music forever, and wrote an extensive essay on his All Night Flight concerts from the 1970s for a forthcoming book of criticism on the composer. But while I love Persian Surgery Dervishes, and Shri Camel, and even that goofy record with John Cale, The Harp of New Albion is the Riley release I’d lug to that desert island.

The album is dedicated to La Monte Young, Riley’s friend and early musical mentor, with whom he also shared a spiritual and musical devotion to the North Indian singer Pandit Pran Nath. Young’s Great Work is The Well-Tuned Piano, an evolving series of compositions for solo piano tuned to just intonation, out of whose sonic and sacred characteristics the sometimes imperious Young makes a great deal of hay. It’s pretty magical, sometimes almost supernatural. When Grammavision released Young’s massive work on vinyl in 1987, Riley declared it a “Holy Work.”

The Harp of New Albion also features a Bösendorfer Imperial, a famously resonant piano, tuned to just intonation, this time with C# as the “pole star.” Riley made the record after taking up composition again following a decade of live jamming, so the improvisations here are couched within structured movements. Like Young, Riley uses this sonic stage to make elliptical soundings of the great Overtone Om at the heart of it all. But as usual, his mysticism is blended with more vernacular voices, like jazz and ragtime. He is a more versatile pianist than Young, and more rollicking as well, so even the sacred sonorities sound more playful than portentous.

Riley also more keenly explores the weird cracks in the tuning scheme by giving each piece a different key and tonal center. This means that some of the pieces, like “The Orchestra of Tao” and the actively unsettling “Circle of Wolves,” bristle with a sour and dissonant daemonism (a wolf fifth is a notoriously unworkable interval associated with some traditional tuning systems). But more impressionistic pieces shimmer like sunrise on the waves; the spare tone clusters in “Riding the Westerlies” sound like Messiaen in a mellow mood—that is, until Riley adds a few barrelhouse seventh chords, which linger in the air like smoke, or fireflies.

The revelation of The Harp of New Albion was powered by my Fuck Covid gift to myself: a fancy German turntable and an analog pre-amp, which works nicely with the vacuumpunk tube amp that came from a small outfit in China. The groove of the album’s 1986 vinyl pressing now fills my living room with angelic partials, ghost resonances, and overtone portals. Listening with full attention, it sometimes seems as if the wayward dissonances weave their way into some spectral order of things more integrated than mere consonance.

Like Van Halen, The Harp of New Albion is a quintessentially California record. In his notes, Riley explains that title was inspired by a harp that found its way to the New World on Francis Drake’s ship The Golden Hind, which, in June 1579, most likely docked somewhere near the Bay Area, which was dubbed Nova Albion. There really was a harp onboard, but according to the legend, which Riley may have invented, the buccaneers—uh, explorers—left the instrument behind, where “it was found by a medicine man who recognized it as a sacred object.” The Indians—Ohlone maybe, or Coastal Miwok—placed the harp on a cliff high above the sea, at “land’s end,” which is also the name of the westernmost point of San Francisco. There the instrument was caressed by the winds, as fog and heat and—who knows?—maybe some suburban stoner with fast fingers gradually detuned the strings into something utterly new.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of The Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription, which gives access to comments, community, and occasional treats. The Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Thanks for your kind words. For me its been important keeping in touch with my earliest love of power chords and famous metal bands, even as the rest of my listening and playing has changed so much. (I mostly just play acoustic these years...) Its just like remembering those connections to early influences or mentors, like the family you are talking about. Gotta give props even when they are goofy!

Great piece. I didn't know about EVH's on the fly B string tuning that is so cool. It is crazy how grief works. AC/DC Is what started me playing guitar, got an epiphone sg, lol. There was a family nearby that was obsessed with rock, and Van Halen especially, the dad built his own guitars and everything. Started jamming with them pretty regularly. EVH passing hit me pretty hard, remembering all of that. That speaker set up sounds amazing, I love your description of "The groove of the album’s 1986 vinyl pressing now fills my living room with angelic partials, ghost resonances, and overtone portals" beautiful stuff.