Tricksters and Cryptids

May News & Notes

I just finished teaching a course at the Pacifica Graduate Institute down in Carpinteria (i.e., on Zoom). The course, on the Trickster, was for graduate students in the Mythological Studies Program. One of my first popular articles was on trickster figures, so the subject is close to my heart. We spent time with some classic mythological figures (Coyote, Hermes, Loki, Eshu Elegbara), explored tricksters in Black American vernacular culture (Br’er Rabbit, John, Stagger Lee), and tracked the lineaments of the trickster within the paranormal scene and among culture jammers like Banksy and the Billboard Liberation Front. We questioned what it means to call such a variable figure an archetype, which implies precisely the sort of universal pattern that the trickster unravels.

We also read Carlos Castaneda, who offers a kind of fractal tricksterdom that reverberates both within and outside the margins of the text. In the closing chapters of the fabulous Journey to Ixtlan (1972), Carlos meets a talking “Chicano coyote” after finally learning how to “stop the world,” an event that itself is precipitated by Don Genaro’s clowning and magic tricks (he makes Castaneda’s car disappear). Tricks, in other words, can open up that crack in the cosmic egg. But they cause havoc as well. Don Juan tells Carlos that having a coyote as an ally is an unfortunate state of affairs. “They are tricksters,” he explains. “It is your fate not to have a dependable animal companion.”

Not that Castaneda himself proved so dependable. After all, these wise and wild chapters play second fiddle in most people’s mind to Castaneda’s biggest trick: convincing everyone—hippies, book reviewers, even many professional anthropologists—that the accounts of his apprenticeship with the mysterious Yaqui Indian Don Juan were factual. Though critics pointed to many inconsistencies, fallacies, and obvious appropriations, Castaneda never backed down from this claim, and I wouldn’t be surprised if some real individuals did lurk behind the amalgamating mask of Don Juan. And though I believe we err in reducing Castaneda’s writing to “fraud,” it seems significant, in a High Weirdness reality-as-Möbius strip kinda way, that some of the most influential and best-selling spiritual books of the 1970s were not New Age nostrums but occult and visionary metafictions—what Daniel Noel calls “shamanovels.”

Trickster: the Many Lives of Carlos Castaneda, a recent podcast doc, dives into the tangled tale of the half-mythic man behind the myth. In accord with the immensely popular true crime framework, the series begins with the end: Castaneda’s death in 1998, and the subsequent disappearance of his senior female disciples (only one of their bodies was ever found). The first part of the series reconstructs Castaneda’s life as a young man, a seeker, an anthropology student, a successful writer. There is not a lot here we didn’t know, but the extensive interviews with friends and colleagues from the early years round out a figure who remains an enigma. The stories we hear concern a master storyteller, after all, and to their credit the podcast producers allow some of that loopiness and instability into their telling. While I wish they had paid more attention to the esoteric meat of these books—which present a kind of magical stoicism as relevant today as ever—I feel that I am in good hands for the second season of the series, which will cover the later Tensegrity years, the growing importance of “the Witches,” and the final, seemingly debased conclusion of a guru trip that managed to be at once insular and transdimensional.

In California, strange sects are like potato chips: it’s tough to stop obsessing over just one. Luckily, the BBC has also just released the The Orgasm Cult, a ten-part podcast doc (around four hours total) about the San Francisco-born “sexuality-focused wellness education company” OneTaste, which achieved great mainstream success in the 2010s before largely unraveling a few years ago.

I’ve been tracking the group for a long time. Jennifer and I checked out a couple of OneTaste events in SF back in the early 2000s, not long after the community was founded by Robert Kandell and Nicole Daedone, a California-born businesswoman, charismatic TedXter, and former Buddhist nun-in-training. At the time, I had already developed a pretty sensitive “cult-dar,” a feel for coercive raps and glassy-eyed affirmations that has come in mighty handy over the years (it works great at tech conferences). At OneTaste, I only got a few pings. Nothing freaky or particularly concerning. Besides, I had already learned that just because a scene is culty doesn’t mean you can’t have a good time!

That said, neither my wife nor I had any interest in leveling up to the group’s main event: Orgasmic Meditation, a peculiarly formalized, even clinical approach to sustained female orgasm. We casually knew a couple who got in deep, and lived at one of the group’s communal houses. They left the group early on, more than a little traumatized by Nicole and her manipulative ways, which included the classic cult tactic of commanding OneTasters to pair up sexually. So while the way the company soared to such mainstream heights later surprised me, the 2018 Bloomberg article that brought the house tumbling down did not.

Sexuality is a deep current within San Francisco’s various transformative cultures, and hacking the framework of sexuality—deconstructing romance, exploring socially unsanctioned practices, pumping things up with magical thinking and altered states—is a time-honored method for conjuring power, bliss, and weirdness. Though Nicole claimed that a mysterious Buddhist monk turned her on to the OM technique, its real roots lay in Lafayette Morehouse, a ‘60s California communal sex scene whose leader was profiled in David Felton’s 1972 classic Mindfuckers. OneTaste was a more contemporary phenomenon, and a very well-named one as well. Though the term samarasa (one taste) is rooted in Dzogchen and tantra, where it can indicate both bliss and equanimity, the tag also has a yummy hedonic overtone. In other words, it’s a great brand, which is what OneTaste increasingly became as Nicole’s aspirations waxed scalar and the business side of the company refined its often coercive and exploitative game—which included hooking up the community’s hot younger women with older moneyed nerds.

The Orgasm Cult is hosted by Nastaran Tavakoli-Far, who combines the classy snark of a BBC skeptic with a refreshing sympathy for wellness culture, spiritual ideas, and California kookery. Though the series throws the language of “cult” around a little loosely for my tastes—which is exactly what a Religious Studies PhD like me would say—it also keeps its mind open about the value of OneTaste’s practices, and acknowledges that some participants had a lot of fun and did some learning along the way. The group ultimately displayed most of the classic hallmarks of charismatic consciousness control, yet its worldly success reminds us that strange sects (with or without the sex) often mirror rather than resist the culture at large. Tavakoli-Far wisely places OneTaste within two such larger contexts, both of which she has covered as a journalist: the women-centered wellness world and the San Francisco technology start-up scene. Indeed, my only real beef with The Orgasm Cult is that, for all that is said about Nicole’s much vaunted charisma, I ended the series with no better sense of her than when I began. Maybe her lawyers were on the line. Or maybe there’s no there there.

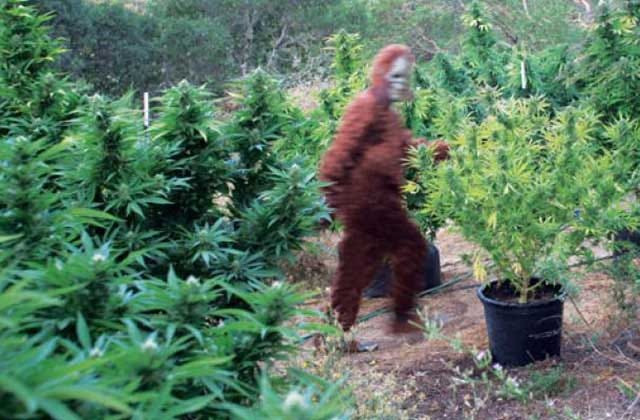

While California is great on the cults, it’s not too shabby on the paranormal either: UFOs over the Mojave; Mt. Shasta encounters with Ascended Masters; the remote viewers and spoon benders at Stanford Research Institute. Then there is the state’s cryptozoological superhero, Bigfoot, who plays a central if evasive role in Sasquatch, a blissfully brief three-parter on Hulu. We begin with a seasoned investigative reporter dude, David Holthouse, who reminisces about trimming weed in northern Mendocino almost thirty years earlier. At the time, he heard tell of red-eyed monsters lurking among the Douglas fir, and one night two terrified tweekers showed up babbling about Bigfoot having torn some growers limb from limb. Though he shrugged it off, the weird tale never let him go.

Thirty years later, after going undercover as a Nazi skinhead and writing about wanting to kill the man who raped him as a child, Holthouse picks through the cold ashes of this possible crime. He goes deep into Mendo in search of Bigfoot, debating the likelihood of a murderous Squatch with various and variously amusing NorCal cryptid hunters. Except Bigfoot’s fat hang tens eventually lead us back towards a more familiar set of deep forest denizens: weed growers. You know the story, or thought you did: what started out as hippie idealism in the ‘70s morphs into an armed criminal enterprise that, while maintaining some freak values, also oozes with violence, paranoia, and racism.

Bolstered with some incredible interviews, Holthouse sets his sights on the kind of good ole stoner boys that John Perry Barlow memorably named “dreadnecks.” Bigfoot proves to be more than a red herring, though, since he plays such a powerful role in the gloomy, eldritch psychogeography of Northern California’s Emerald Triangle, the cannabis-growing outback that is the real subject of Sasquatch. For though Holthouse pursues some tantalizing and disturbing threads—murdered Mexican nationals, the lethal traps protecting some grows, militarized government thugs—the search goes cold. This lack of closure might be disappointing if Holthouse and his quest didn’t prove so engaging on their own terms. In fact, Sasquatch might be even better for not tying things up in a bloody bow. If part of our attraction to true crime is the opportunity to wrestle with human darkness, to imprison our fears into the formulas of fact, then we have to make room as well for the ones that got away, the horrors that remain nameless, that trail off into shadow, just like the elusive Sasquatch making her way deeper into the woods.

Upcoming Events

(•) I usually get these monthly “News & Notes” posts out before the SF Psychedelic Sangha gatherings, which take place the first Saturday of the month, but this May it didn’t happen (and the crowd was smaller). One unfortunate conclusion that has been forced upon me is that, while I like to imagine myself as a writing monster, the reality is that even doing three posts a month—including “Ask Dr. D.” for paid subscribers—takes a lot of time and energy. Since I have a book project to complete this summer (more on that later), something’s gotta give. Going forward, there may be some more lazy launches, along with attempts at shorter, snappier posts. Most of you probably won’t notice, but there it is.

(•) Konrad Becker, an impish Viennese theorist of dark digital culture, just let me know that his latest anthology, Digital Unconscious: Nervous Systems and Uncanny Predictions, which he co-edited with Felix Stadler, is coming out this month on Autonomedia. These are folks I met back in the edgy media theory days of the ‘90s, and they never lost that future-critical edge. The book includes essays from Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Critical Art Ensemble, Lydia H. Liu (author of the excellent The Freudian Robot), Michael Taussig, and the mysterious El Iblis Shah. I contributed something as well, and I barely remember writing it—the digital unconscious in action! The book launch, featuring Bifo, CAE, and Katja Mayer, will take place on Tuesday, May 11, at 10 am PT.

(•) Next month I will be participating in a one-day conference called “Accessing the Ineffable: Depth Psychology, Religious Experience, and the Further Reaches of Consciousness.” The gathering is organized by David Odorisio of the afore-mentioned Pacifica Graduate Institute, and will feature talks on a variety of far-out mindstates, including dreams, seances, and spirit possession (which some people increasingly describe as “incorporation”). Psychedelics will be addressed in talks by Christopher Bache (LSD and the Mind of the Universe, 2019), William Barnard (Exploring Unseen Worlds: William James and the Philosophy of Mysticism, 1997), and myself. The all-day event will take place on Saturday, June 19, starting at 9am PT. You can register here; I hope to have passes or reduced rates available next month.

Links

(*) A few months ago, I was invited to give a lecture at the Philosophy & Religion Forum at the University of Southern Mississippi. I took advantage of the opportunity to synthesize a lot of the ideas about conspiracy theory, paranoid media, and visionary esoterica that kept me company during a whole year thinking and talking about QAnon and its relationship to alternative religion and psychedelics. I wanted to pursue my understanding of the gnostic dimensions of the new mythologies of global mind control, and to place those ideas into a critique of power that drew from the inspiring work of the liberal theologian Walter Wink. The result was “Arkonlogy: The Gnostic Mythologies of Conspiracy.” Even if, like me, you can’t find the time to finish watching that Q documentary, I still think you will dig it.

(*) Someone just forwarded me a list of the 100 most influential people in psychedelics, put together by the wise and well-seasoned psychonauts behind, uh, the Psychedelic Invest website. I could laugh and cry about this thing all day long, though it does provide a useful snapshot of an emerging industry as filtered through a contemporary notion of “influence” based solely on media reach, financial clout, and institutional status—which is fair enough these days. Tim Ferris is top of the heap, just edging out Joe Rogan; Brian Muraresku, who wrote brilliantly about druggy mystery cults in the bestselling The Immortality Key, is number 18, even though he proudly remains a psychedelic virgin. The first solo woman clocks in at number 25, but thank goddess it is Amanda Feilding, who appears just before that horrible woman from Compass Pathways.

A few months ago I was a guest on the podcast of number 58 on the list, Aubrey Marcus, who is described there as “an experimentalist, unconventional fitness junkie, and human optimizer.” Apparently Aubrey’s human performance company Onnit is also “one of the fastest growing companies in America.” I like to talk to people, and Aubrey is a thoughtful modern Stoic dude who has definitely forged his own path. I am happy with how the conversation came out. While Aubrey was maybe a little taken aback by some of my skepticism, we found a lot of common ground in our enthusiasm for the experimental, and I appreciated the way he reflected on his own role as an influencer trying to guide folks responsibly through the maelstrom of the psychedelic renaissance.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription if you can. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar.

Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so please pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

The Arkonology talk was great. Really helped me with developing my own sometimes paranoid intuitions that have resulted from spiritual seeking combined with a deep dive into geopolitics and modern power structures, into something more tangible. I've had this sense of our institutions having a sort of emergent, agent-like behavior (or as you put, a "spiritual quality") for some time. It's a hard thing to juxtapose with a skeptical, rational understanding of reality. It's especially difficult to not be frightened by the implications. As someone who was raised Catholic and abandoned it in my teens, I am uncomfortable with the implication that I might find some of the answers to my searching in theology, but the ideas resonated strongly with me. Perhaps it's time to read some Walter Wink.

Hi Erik! I really enjoyed the Carlos Castaneda podcast documentary. Do you have any info as to where we can hear Part 2? It's nowhere on the site with the six chapters of Part 1. Thanks!