Slanted and Disenchanted

David Crosby's "Laughing"

[Read on the website for a more luxurious experience.]

If a lot of your cultural expertise and passion lies way back there in the early 1970s, then the 2020s are gravy-train times. Every day, month, or year, you can justify a dive into the archives with the flimsiest of hooks: the 50th anniversary. Until today, I had not played this particular card — partly because of my fear that once I start, I won’t be able to stop. With that cultural chronotype in mind, I have already started pushing potential Burning Shore pieces onto the back burner (Mumbo Jumbo, 1972; Kung Fu, 1972, Gravitys Rainbow, 1973). But don’t worry, there are too many contemporary things I want to write about to fully succumb to retromania. Still...

Fifty years ago to the month, David Crosby released If I Could Only Remember My Name, his first solo album. Panned by Rolling Stone and Robert Christgau at the time — Christgau called Crosby’s performance “disgraceful” — the album has come to be recognized as a head classic and Crosby’s defining statement. (For great background, check out the recent Deadcast where Jesse Jarnow talks to Coz about the album and his relationship with the Dead, who were recording American Beauty at the same studio around the same time.)

Unlike Deja Vu, the CSN&Y megahit that came out the year before (and which to my ears is now hopelessly locked in pop-hippie amber), If I Could Only Remember My Name finds Crosby hitting those harmonic highs while unraveling in all the right ways. A treasure trove of California players come and go throughout the album sessions — Neil Young, Graham Nash, Joni Mitchell, plus most of the Dead and Jefferson Airplane. Instead of playing a bloated all-star game, these friends and fellow travelers drift together in stoned camaraderie, softening Crosby’s outsize persona and creating a shambling but often scintillating hang-out vibe that gives listeners a seat at the fire and hands them a doobie to boot.

The album title, one of the best of the era, rings true as a prophecy of the countercultural identity crisis that would come to characterize the whole decade. But it’s best seen as Crosby’s ironic comment on his own headspace at the time. Just as Deja Vu was making Crosby the rock star a household name, the mustachioed man himself was trying to obliterate himself. Grieving the loss of his longtime girlfriend Christine Hinton, killed in a car accident shortly after the couple moved from LA to the Bay the year before, the Croz was consuming tons of hard drugs. When nightly jam sessions at San Francisco’s Wally Heider Studios would wind down, he would drive up to Mt. Tamalpais in Marin to mourn, get high, or higher, and maybe temporarily blot out that pesky identity.

An echo of those jags can be heard on “Tamalpais High (At About 3),” which finds Crosby and Nash backed by most of the Dead, plus Jorma in fine back-porch mode.

Laurel Canyon harmonies dart deftly and wordlessly, like a pair of golden butterflies, following lines of flight that Crosby later described as “nonparallel.” The second half of the song melts into a Dead zone, one of those pensive, mellow meanders familiar from live renditions of “Morning Dew” or “Dark Star.” The loose groove turns around and somehow makes the opening vocals seem spontaneous, as if the whole thing is a jam, and even though its only three and a half minutes long, it sounds like it goes on forever, just like grief and certain highs. (Here is the extended improvisation you can hear looming behind the edited track.)

But that’s not the song I really want to talk about.

“Laughing,” the last song on side one of the LP, is hands down my favorite seeker song of the countercultural era. Since you probably haven’t heard it in awhile, or maybe never heard it at all (lucky you), let’s give it a digital spin.

We don’t use the term “seeker” much these days, which is kind of a shame. As the religious historian Leigh Schmidt illuminates in his book Restless Souls, the modern sense of “seeker” emerges at the end of the nineteenth century, as liberal Protestantism gets so loose that it arguably ceases being Christianity, and becomes Transcendentalism, or New Thought, or Theosophy, or, increasingly, something undefined and personal, roving and uprooted from homegrown traditions, open to ideas and symbols and practices from around the world, particularly the East, and especially keen on cultivating direct experience of the sacred. The seeker sensibility would bloom significantly in the postwar world. The Beats took it up in the fifties, as did many of their beatnik followers, and so too the far more numerous hippies and travelers and self-realizers and proto-New Agers of the late ‘60s and ‘70s, many of whom would self-identify as “seekers.”

In the eyes of many social critics, the seeker was nothing more than the pupa stage for today’s spiritual consumer: an atomized neoliberal self-empowerment junkie, mixing and matching a “cafeteria religion” and pampering the ego they are claiming to overcome. Perhaps we no longer speak of seekers because we are more comfortable as finders, or better yet, buyers — not just of Goop chakra tech, but of lifestyles, or Instagram paradigms, or self-help regimens that buffer us from the dark nights and stark confrontations that arguably undergird authentic spirituality.

But let’s not toss the baby out with the Emotional Detox Soak bathwater. In my (admittedly slanted) view, a mature seeker is, like the Beats of yore, a spiritual existentialist. The seeker is not a finder, or a knower, or a master. They are always on the road, or traversing, even drifting, along Krishnamurti’s “pathless path.” As such, they distrust settled solutions or popular formulas, and prefer the company of fellow travelers or even reprobates to cults or congregations. Seekers can and do find teachers, and take up practices of discipline and devotion, just like Leonard Cohen did. But if one remains a seeker in one’s heart there is always a certain distance or tension. Longing fuels the entire quest, and that longing is always oriented to the beyond, to the not-yet, to a liberation that almost certainly won’t happen the way one imagines, and may very well not happen at all.

***

David Crosby was no seeker. He gobbled lots of acid, sure, but as a cantankerous freak rather than a barefoot mystic. He was pals with Jerry Garcia for a reason. But he did write “Laughing” for a seeker. On Twitter, Crosby admitted that he composed the tune for George Harrison, and that it was about the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the Transcendental Meditation guru who briefly enthralled the Fab Four during their 1968 TM retreat in Rishikiesh. (Paul and Ringo left early, the latter missing his baked beans.) But the song was also written for Harrison in a different sense: as a soft plea for him to wake up and realize that nobody’s got the ultimate answer.

I don’t know when Crosby wrote “Laughing,” but by 1970, Harrison had moved on from the Maharishi. That’s what seekers do: they move on. The exact reasons for the group’s fall-out with Sexy Sadie have grown murkier in the long light of time — though the Maharishi was definitely grabbing after Beatles cash, his more famous grab for Mia Farrow may well have been a calculated lie passed on to the Beatles to sorrow them on the guru. But as Scorsece’s doc Living in the Material World shows, Harrison never stopped being a seeker, and he moved through Krishna Consciousness and variations of Hindu meditation and devotion throughout his time on earth. And his religious quest didn’t stop him from being an occasionally great songwriter, or the organizer of the first massive benefit concert (for Bangladesh), or the producer of a blasphemous film made by his mates in Monty Python.

But that’s part of the genius of “Laughing”, whose deeper message, which Crosby perhaps did not intend, is that disenchantment is, or can be, or should be, part of the path. The three verses show three stages of this disillusionment, even as the gorgeous music voices the yearning that keeps driving the quest. Stage one:

I thought I met a man

who said he knew a man

who knew what was going on

I was mistaken

Only another stranger

That I knew

The first stage turns on the stark limitations of spiritual knowledge claims in a human world of talk, hype, and mimetic desire (desire for what the other desires). The seeker meets a man who says he knows a Man Who Knows. As the digital mediascape amply shows, people are powerfully attracted to the confidence of such men (and sometimes women), even when they don’t know shit. In spiritual guru scenes, the teacher often doesn’t claim holiness directly, but allows their close followers to build up the tale. This indirection intensifies charisma into a social fact.

In this verse the seeker realizes that the Man Who Knows is just a rumor, something someone said about someone and nothing more. He knows the guy who had the encounter, but only in the way that we only know anything: provisionally, dependent on circumstances, and easily distorted by desire and fantasy. The mistake here is to forget that knowledge claims are always mediated, even (or especially) spiritual ones. Even the most enthusiastic and intimate interlocutor remains, in some intangible sense, a stranger. There is always a gap. In the words of the Zen master Homeless Kodo, who wandered around Japan teaching layfolk instead of monks, “you can’t even trade so much as a single fart with the next guy.”

In the next stage, the seeker seems to have transcended the mediation of language and rumor by directly encountering a spiritual source:

I thought I found a light

To guide me through my night

And all this darkness

I was mistaken

Only reflections of a shadow

That I saw

Here a direct and extraordinary experience appears to take the singer beyond rumor or language or even knowledge. Such mystical or religious experiences are of key significance to the modern seeker. A dream, a forest vision, an acid trip, a flash of meditative satori — these moments seem to transcend mediation and provide a deeper orientation. Here, at last, is confirmation, a shelter in the storm, a guide. But the moment passes, the light dims, and all that’s left in your memory is a reflection of the past, whose meaning you can hold no more easily than you can clutch a shadow. Satori is now only “satori,” and Homeless Kodo would probably suggest you just ditch it, and drink your darkness black.

Finally, the kicker:

And I thought

I’d seen someone

Who seemed at last

To know the truth

I was mistaken

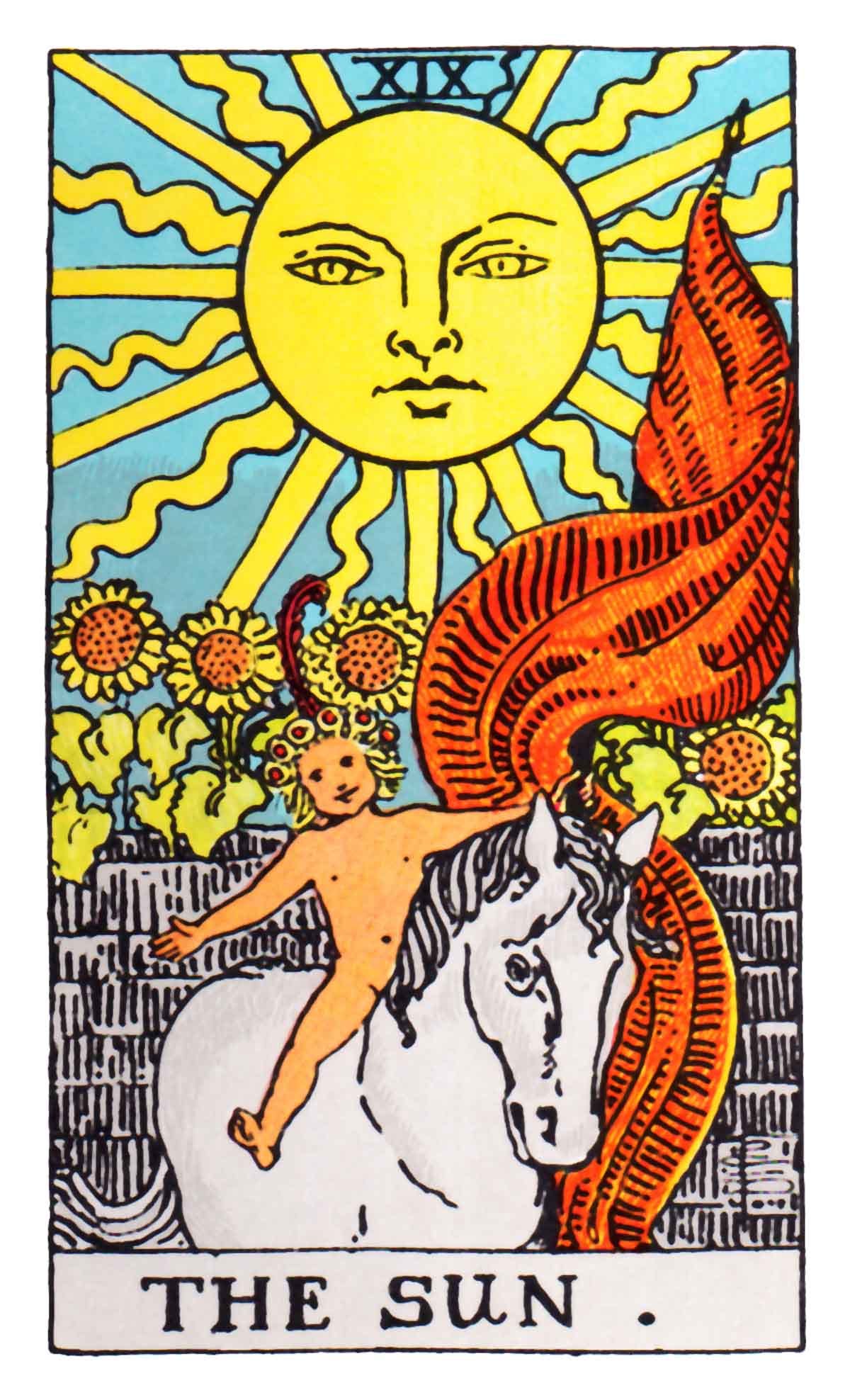

Only a child laughing

In the sun

Here we meet the guru at last, the Man (presumably) Who Knows. But as the rhyme of “seen” and “seemed” hints, the seeker has not escaped the mirrorhouse of projection, reflection, maybe even misdirection. At the same time — and unexpectedly for a song with such a disenchanting undertow — this disillusionment does not leave the seeker bitter and bereft. The guru is not exposed as a liar or a lech, a joker or a thief, but “only” a child laughing in the sun. The seeker’s mistake did not lay in identifying something special in this person, but in believing — hoping — that this specialness had something to do with knowing the truth. Instead, the numinous boils down to an ordinary state of radiant and childlike joy. To wit:

The figure of the happy child was a crucial cultural icon during the ‘60s, reflecting the era’s powerful investment in ideas of youth, natural innocence, and spontaneous play. Children were seen not as little beasts that required strict training but as pure spirits not yet dragged down into the hole of “civilization,” which radicals and freaks and seekers were trying, in their different ways, to claw their way out of. The child didn’t need to get back to the garden; the child was already there.

So while the seeker of “Laughing” faces disappointment in the first two verses, their final encounter with the giggling tyke provides something more positive. Perhaps this state of being is the goal of the pathless path, one that requires neither faith nor knowledge but mere being. Speaking of which, this is how Wallace Stevens describes a similar realization in the third stanza of his poem “Of Mere Being.”

You know then that it is not the reason

That makes us happy or unhappy

The bird sings. Its feathers shine.

Though we are still in the realm of knowledge here, this knowledge is bare: the singing bird, its feathers shining, just is, without rhyme or reason. Is this gnosis, or nothingness? Similarly, Crosby’s sun-baked child confirms both sides of the seeker’s search, fulfilling both the longing and the doubt. The kid’s laughter is at once spiritual and meaningless, enchanted and disenchanted.

We can further limn this state of hippie beatitude by way of Alan Watts’ notion of “purposeless play.” The phrase itself comes from a little speech that Watts gives to his fellow trippers in A Joyous Cosmology (1962), his sensitive and revelatory account of an LSD experience he had with his friends at Druid Heights, on the southern slopes of Mt. Tamalpais. Glimpsing something at once profound and purely contingent, Watts proclaims to his friends:

Listen, there’s something I must tell. I’ve never, never seen it so clearly. But it doesn’t matter a bit if you don't understand, because each one of you is quite perfect as you are, even if you don’t know it. Life is basically a gesture, but no one, no thing, is making it. There is no necessity for it to happen, and none for it to go on happening. For it isn’t being driven by anything; it just happens freely of itself. It’s a gesture of motion, of sound, of color, and just as no one is making it, it isn’t happening to anyone. There is simply no problem of life; it is completely purposeless play—exuberance which is its own end.

What I love about Watts’s realization here is that despite its radical affirmation of life, there is something terrifying about purposeless play. Life may be exuberant, a laughing child of motion, sound, and color, but there is no ground anywhere, no justification, no reason, no sense. The bird sings, its feathers shine. Even if we set aside the moral problems raised by this vision, which Watts’s critics link to his alcoholism and womanizing, there is an existential chill to purposeless play. Perhaps this is what the seeker was working up to all along: the fierce joy and courage required to laugh with, and at, this glittering void.

The last verse of “Laughing” ends about two-thirds of the way through the track, and the rest of the tune is taken up with a mellow jam, some harmonies from Joni, and a long pedal steel solo by Jerry Garcia, who was spending a lot of time with Crosby in the studio because it was the best way he knew how to support a friend going through a rough patch. Garcia had already contributed the dancing steel guitar in CSN&Y’s “Teach Your Children,” but on “Laughing” we are far from Bakersfield. Jerry’s lead leaps from High Tamaplais, takes flight into the setting sun, and descends like Redwood Creek into the golden sea, where the solo darkens to the minor slightly just before the fade.

Throughout the song, the music has been gently laughing along with us, never submitting to the seeker’s disappointment. But in Jerry’s solo the purposeless play of the jam crystalizes into something more like a cry. What is this sound we hear? It is the sound of yearning, which has been both nurturing and driving the seeker from the very beginning, and which in the end may be the most vulnerable and beautiful and honest thing that remains once the seeker sees through their seeking.

I hope you enjoyed this flicker of Burning Shore. Please consider a paid subscription — which opens up extra features, like the monthly “Ask Dr. D.” column. Or you can drop a tip in my Tip Jar. Burning Shore only grows by word of mouth, so pass this along to someone who might dig it. Thanks!

Ooof. Lots of personal confluence in this one.

Is everything meta? I kinda think the answer is yes. My belfry bats resonated with your gongs on the nature of a “mature seeker” but wonder how one attains a state of maturity out of the reality of persistent uncertainty. I’m trying but it feels like an infinite babe-in-the-woods moment.

Your words and themes here entwine with threads of my history and meaning-surfing, but at awkward angles. I just wanted to share how they conspired in my mind.

I never got into Crosby beyond the hits, but my dad played and hung out with many of the Bay Area rock artists of that time, including Santana and the Dead. He was a hustling jazz trumpeter trying to find a place in Rock & Roll, and chose that path instead of being present in my life. When I was 30, I tracked him down while he was performing at Pier 23 Cafe on the Embarcadero. During a break between sets I introduced myself.

We never developed a relationship beyond sparse pleasantries, and he often filled those moments with famous musician name drops and related stories. He died suddenly in 2008, alone, between parked cars in Pacifica. Much of his life, at least from his perspective, is permanently locked in mystery. My younger dadhalf-siblings confirm that I have a lot of his traits, in spite of his total absence, and that is both intriguing and terrifying. It makes me ponder the scope of "spooky actions at a distance”.

Was my dad a seeker or just a hustling drug taking braggart artist? Both? Was he haunted or inspired by brushing shoulders with success and fame? What shadows dogged him? What parts of this quandary live in me?

All of the above, I assume.

Anyway, thanks for your Thought-Fu, Shrugged Shoulders style.

Erik, thanks for that. I can`t believe I`d never heard “Laughing” or any of that album before.

`Nice one` to use the parlance of the times.

Alan Watts presented that the whole idea of hitching up with a guru or following a path is to eventually find out that you don`t need to. The tricky bit is, we have to do it in order to get to that point; we have to get into it to get out of it and the fool has to persist in his folly in order to become wise as Blake said and Alan Watts was fond of referencing.

Even Krishnamurti spent decades on the Theosophical path with all its steps and handrails before he headed off into his pathless land.

I`m not surprised that Alan Watts is still wildly popular after so long (another 50 year anniversary for your list!). Apart from anything else, his emphasis on play and purposelessness can be a great medicine for today`s spiritual consumer culture with its obsession with getting to the next level/chakra/dimension/plane/state etc and acting like a spiritual tourist fighting for his seat on the bus, whilst missing the beauty of the journey.